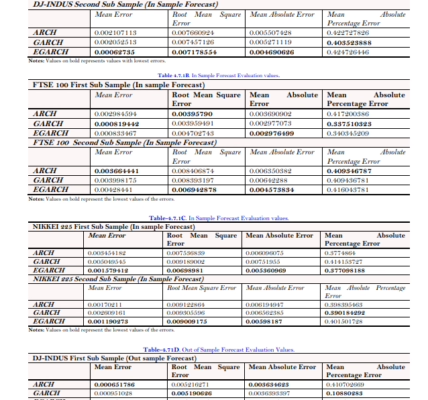

Shocks affecting disposable income of households, Three fiscal shocks crucially affect the disposable income of households. These shocks are associated with direct taxes paid by households, social contributions paid by households and social benefits received by households (i.e. social transfers in the model). Not only the current disposable income is influenced by the three fiscal instruments, but also the permanent disposable income. The former plays a crucial role in the consumption of rule-of-thumb consumers. The latter, in turn, drives the consumption of optimising households. Subsection C.1 in the appendix lays out the details on the formation of disposable income and how it affects private consumption for the two types of consumers.

The three fiscal instruments discussed here, if expansionary, all increase the current disposable income (see Figure 6). As rule-of-thumb households spend whatever income they have at their disposal, their consumption increases instantaneously. The baseline calibration of the ECB-BASE assumes 1/3 share of rule-of-thumb consumers.22 The reaction of these consumers immediately provides a boost to economic activity. Following the improved economic conditions, the permanent disposable income also increases, positively influencing the target private consumption. As time passes by, optimising households adjust their consumption gradually towards the target in accordance with the polynomial adjustment costs (PAC) specification.23 The reaction of optimising households makes the response of private consumption (and output) last longer than fiscal shocks themselves (note that the target consumption remains considerably above zero within the simulation horizon).

Rule-of-thumb households play a key role in the translation of income into consumption. They

are also primarily responsible for the differences between the three shocks noticeable in Figure 6. R-o-T consumers do not own wealth, and as such, they do not benefit from the property income (i.e. only from labour and transfer income, see Subsection C.1 in the appendix for the detailed description of the disposable income). A considerable share of direct taxes paid by households, however, is related to property income (see Figure C.2 in the appendix). Therefore, any changes to direct taxes will impact more optimisers, who react sluggishly, than R-o-T consumers. For this reason, direct tax paid by households is less stimulative than household social contributions and government transfers. In addition, social contributions and government transfers induce bigger changes to the overall disposable income than direct taxes. This phenomenon occurs because a part of social contributions and social transfers (mostly pensions) is operated by private sector funds, which follow the policies of the government (see Figure C.3 in the appendix on the share of the government in total contributions/ transfers).

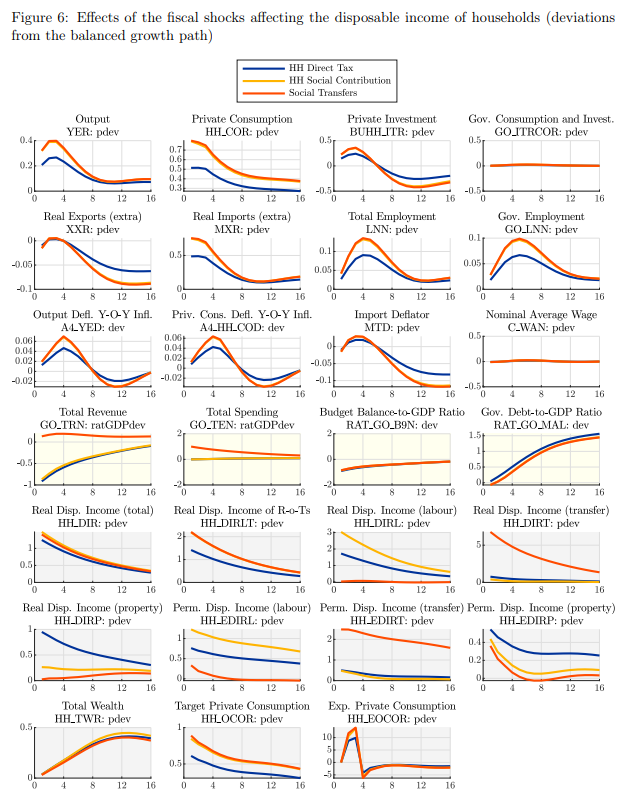

Firm social contributions shock

While social contributions paid by firms serve, in principle, the same purpose of funding the social security system, as those paid by households, their propagation mechanism and economic effects are quite different. Naturally, social contributions paid by firms directly affect employers rather than employees. This feature is primarily the reason for devoting a separate subsection to this shock and not bundling it together with the three shocks affecting the disposable income of households. Nevertheless, to give some perspective, the subsection contrasts the social contributions of firms against those of households (see Figure 7) and emphasises relevant differences.

A fiscal expansion of 1% of GDP through social contributions paid by firms directly affects

total compensation, which initially drops by around 2%. As labour costs for employers fall,

firms have incentives to increase employment. This development lifts the overall compensation with time and more than offsets the direct effects of the SSC cut during the outer quarters.

Additional employment and lower prices due to the labour cost reduction eventually lift the

disposable income of households. The gain leads to an increase in private consumption and stimulates output. The reaction of private investment to favourable economic conditions

further strengthens the output, which eventually noticeably increases (by 0.3% after three years). Since there is no immediate reaction of the disposable income to the cut in social contributions paid by firms, the shock propagation takes place only gradually. The shock omits the Rule-of-thumb consumers with a high marginal propensity to consume, which are able to provide an instant boost to private consumption. This situation stands in contrast to social contributions paid by households, which lead to a quick uplift in private consumption. Overall, the effects of the two shocks on real output are of a similar magnitude but different when it comes to the time profile (i.e. delayed vs instant). Another difference between the two shocks relates to the effects on prices. Since contributions paid by firms reduce labour costs, they put a noticeable downward pressure on inflation.

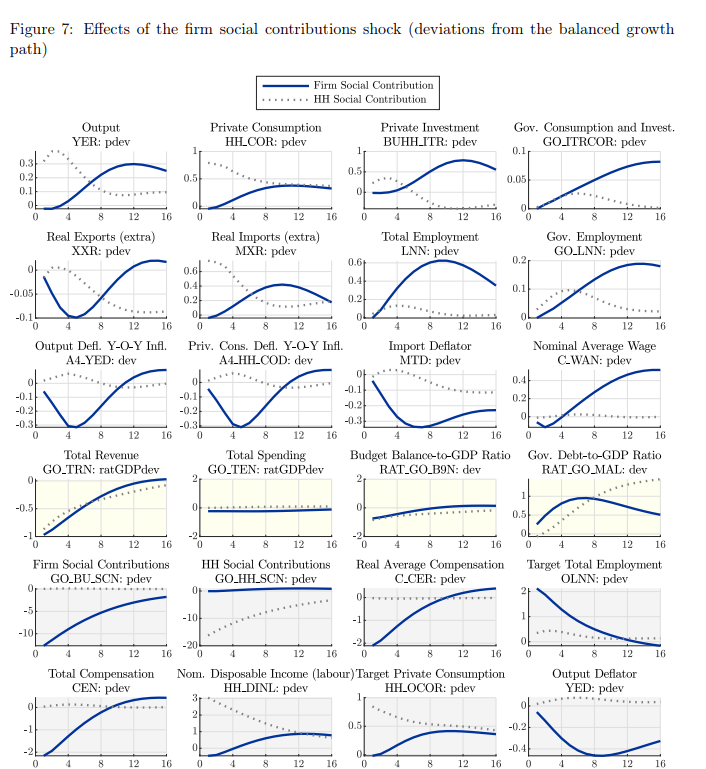

Firm direct tax shock

Corporate taxes constitute in the model a powerful tool to affect business investment. The

corporate tax rate entering the business investment optimisation problem is linked to the direct

taxes payable by firms present in the fiscal block. To put the propagation of the direct tax by

firms shock into perspective, the below description features a comparison with the direct tax by households shock described in Subsection 4.1. A reduction in direct taxes paid by firms by 1% of GDP is associated with a significant cut to

the corporate income tax rate (above 2 percentage points, see Figure 8). The cut has immediate implications for the user cost of capital, which falls as a consequence. The reduction positively affects the target value of business investment (see Subsection C.2 in the appendix containing the description of the relationship between key investment variables). A change in the target value does not immediately induce adjustments to actual business investment. Only over time, in accordance with the PAC specification, private investment catches up, thereby gaining strength gradually.

It is evident from Figure 8 that the two types of taxes, namely those paid by firms and households, have distinct macroeconomic effects. The corporate tax cut operates primarily through private investment, which consists mainly of business investment (around 2/3 in the euro area).

Also, the effects materialise gradually because the corporate tax rate directly influences only the target variable. By contrast, a cut in direct taxes paid by households manifests itself primarily through private consumption. Also, the response is imminent as changes in disposable income instantly operate through the consumption of R-o-T consumers.

Sources:

Working Paper Series

Fiscal policy in the semi-structural model ECB-BASE