Despite modest growth, the UK economy faces a complex landscape. The International Monetary Fund (IMF) predicts the UK will be the second-fastest-growing G7 economy in 2025, with a projected growth rate of 1.3%. However, this also comes with the challenge of facing the highest inflation rate in the G7. Economists and business groups point to significant headwinds. The National Institute of Economic and Social Research describes a summer of difficulty for businesses, noting that regaining economic momentum “hinges on restoring business confidence and reducing uncertainty”. This sentiment is echoed by the CBI, which reports that firms are “choosing to sit tight on hiring and investment until there’s more clarity on the policy outlook”. Global Investors and the wider British public from all corners of the globe in all Commonwealth Countries are waiting on the government’s upcoming budget. Meanwhile, Chancellor Rachel Reeves has acknowledged public sentiment that the economy “feels stuck,” and the budget is expected to outline plans to address this and stimulate growth.

Latest UK GDP Figures

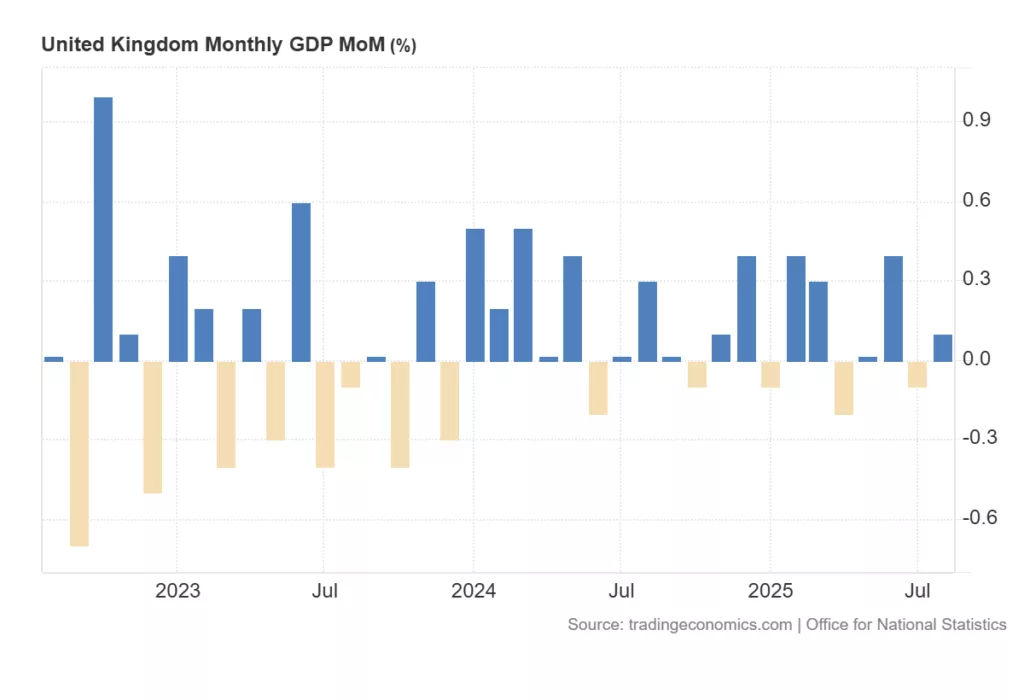

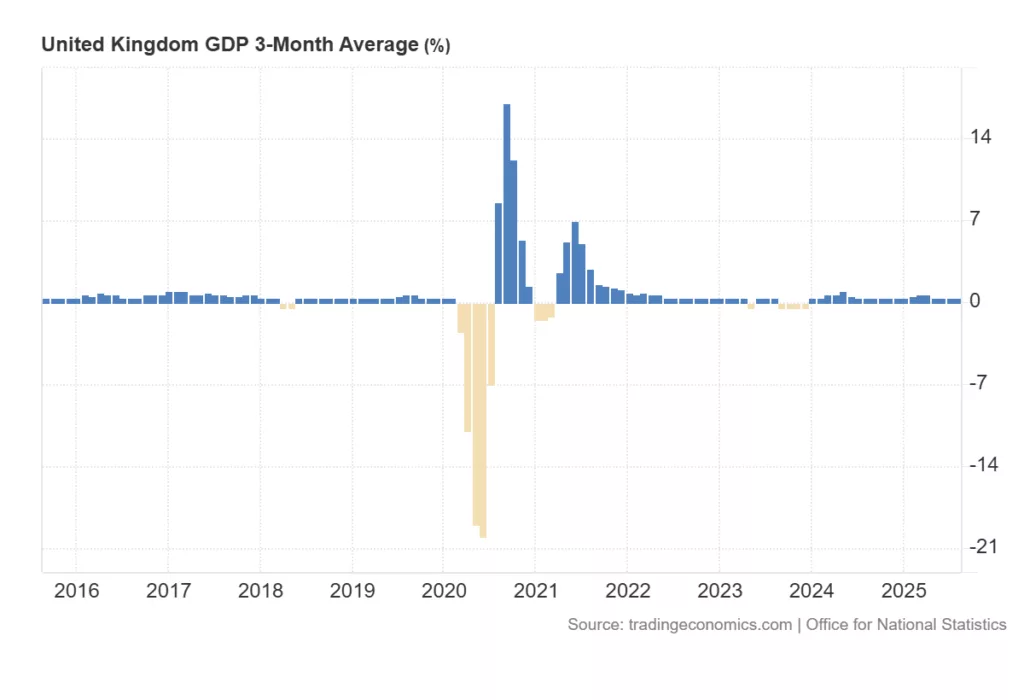

| Metric | August 2025 Performance | Previous Month (July 2025) | Data Source Link |

|---|---|---|---|

| Monthly GDP Growth | +0.1% | -0.1% (revised) | ONS GDP Monthly Estimate, Aug 2025 |

| 3-Month Average GDP Growth | +0.3% | +0.2% | ONS 3-Month GDP Growth Data |

| Annual GDP Growth (YoY) | +1.3% | +1.5% | ONS Annual GDP Growth Data |

Sector Performance in August

Output grew 0.4% month-on-month, rebounding from a 0.4% contraction in July. Key drivers included a 0.7% rise in manufacturing, a 0.4% increase in electricity and gas supply, and a 0.3% growth in water supply. This was partially offset by a significant 2.3% fall in mining and quarrying. Output showed no growth (0.0%) for the second consecutive month. Performance was uneven, with growth in areas like administrative services (up 1.0%) and health and social work (up 0.4%) being cancelled out by declines in retail trade, transport, and arts/entertainment.

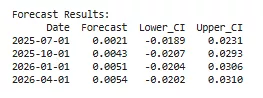

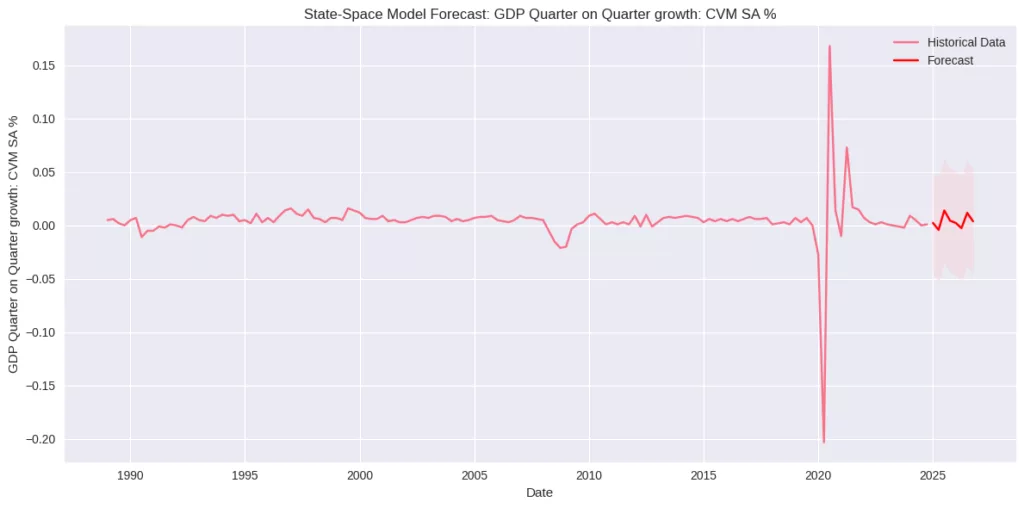

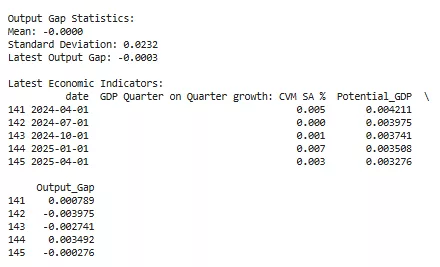

Forecast’s perfectly in line with ONS data, as you can see now

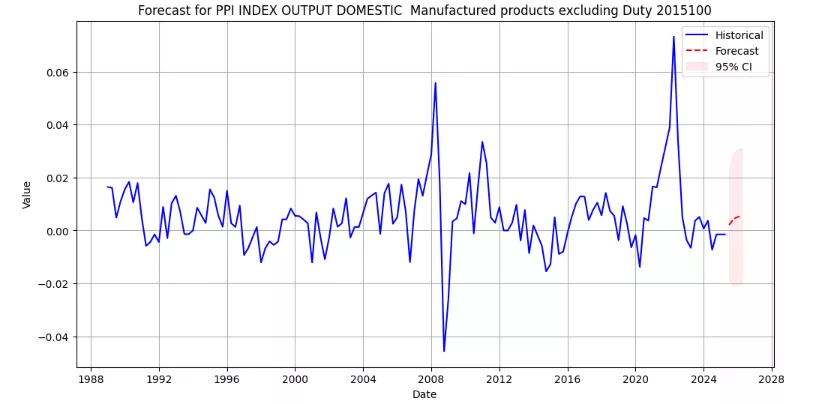

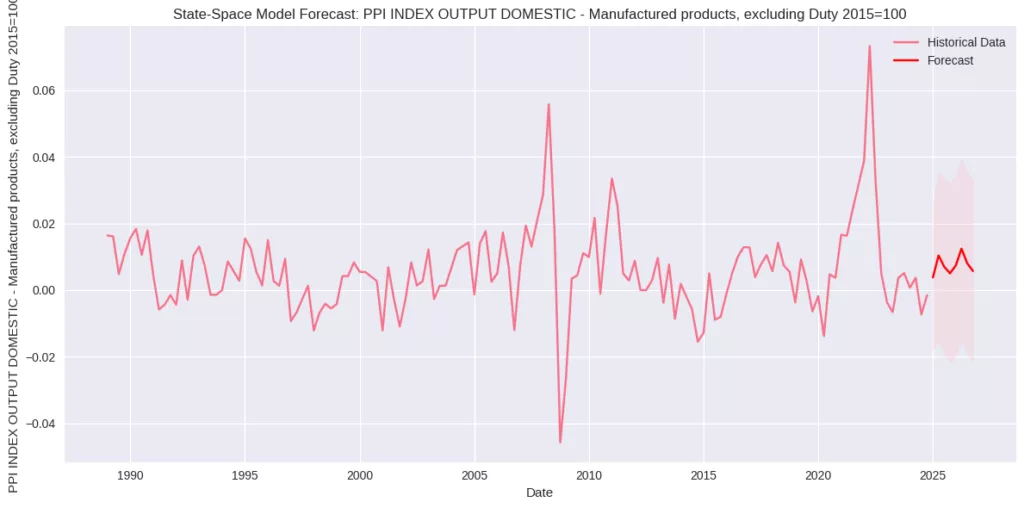

Here we have the quarter-on-quarter PPI Index Output for Manufactured products with the following projected forecast, as a proxy of Manufacturing activity

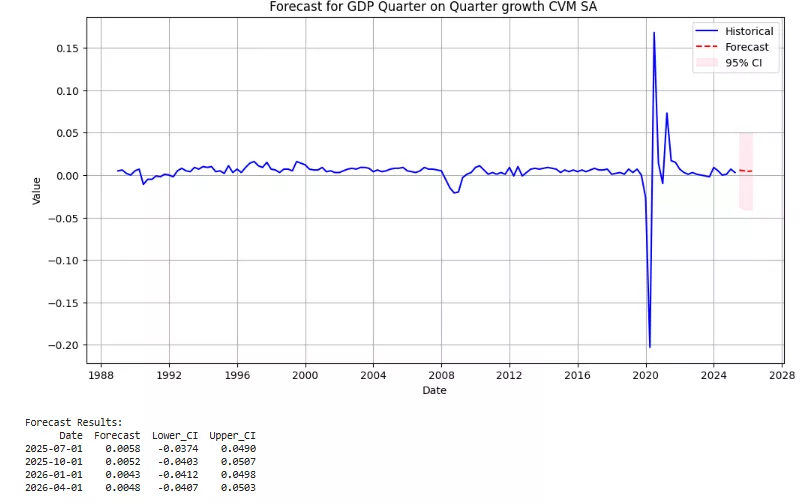

Our Arima (0,0,1) model generated a Real GDP Growth Forecast Quarter-on-Quarter of 0,58% ( red dashed line) in Q3 and 0,52% in Q4 2025, while 0,43% in Q1 2026 and 0,48% in Q2 2026. Our estimates were slightly higher than the actual ONS data,

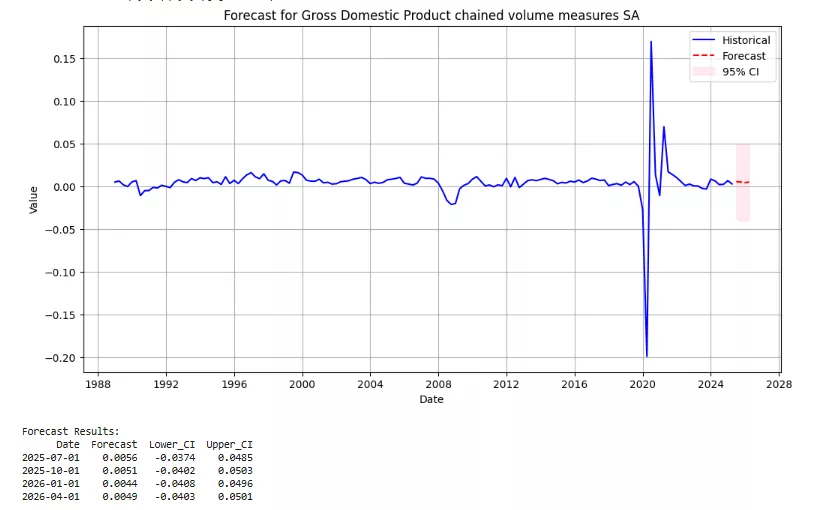

Additionally, GDP chained volume measure estimates are almost in line with the latest ONS macro-data. Our forecast was 0.56% in Q3, 0.51% in Q4, 0.44% in Q1 2026, and 0.49% in Q2 2026.

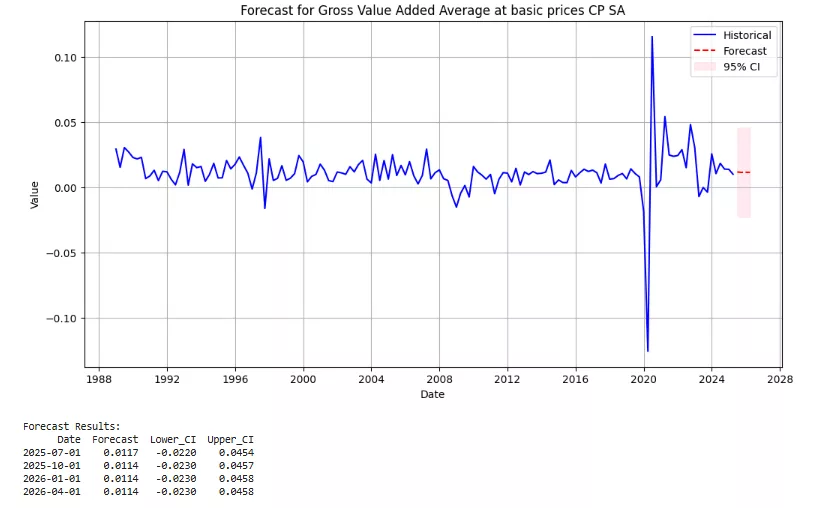

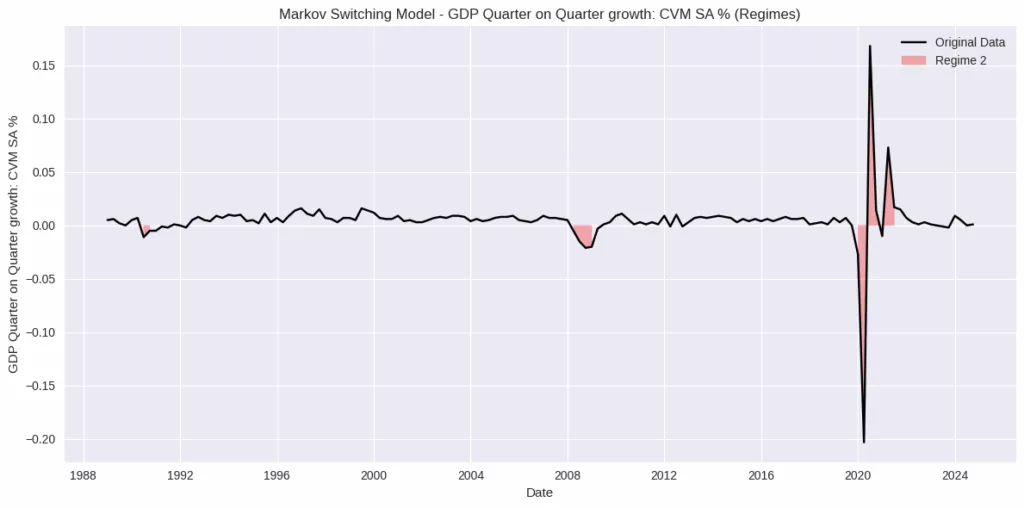

The Forecast of Gross Value Added proves to be in line with year-on-year growth figures of 1,3%, our free range forecast bounds 1,14% | 1,17% up to Q2 2026. Also with a Markov-Switching model, the long-run average quarter-on-quarter estimate describes the UK economy’s steady state with an average quarterly GDP of 0.54%, slightly above actual output; however, the Markov-switching model doesn’t forecast any change in the moderate economic growth trend, unless unforeseen exogenous shocks could switch the economic growth regime into recession with negative average growth of -0.29%.

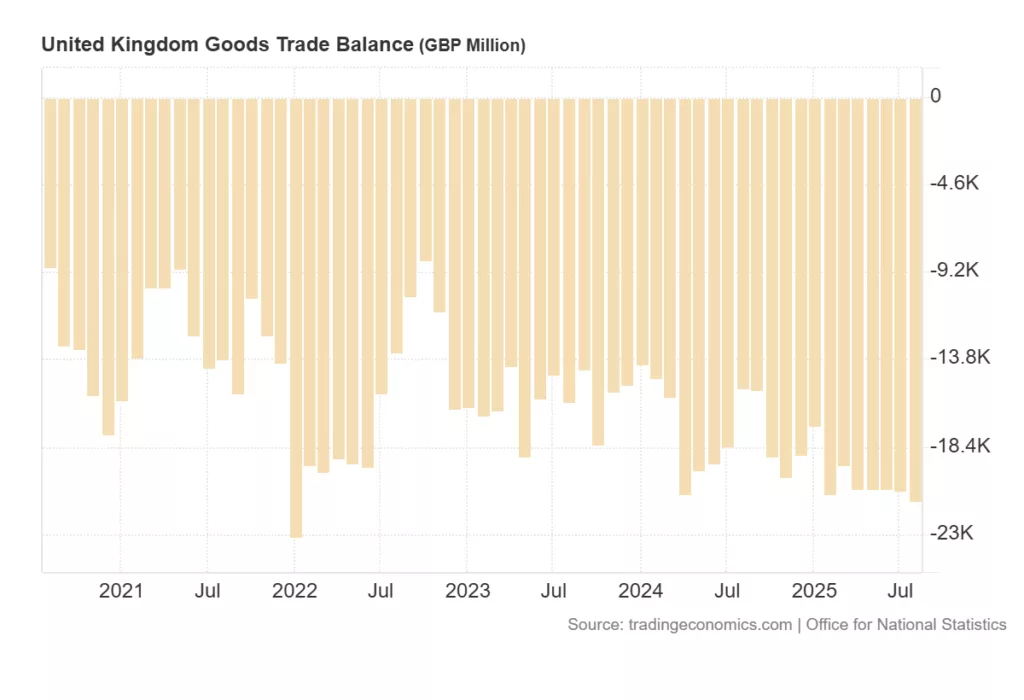

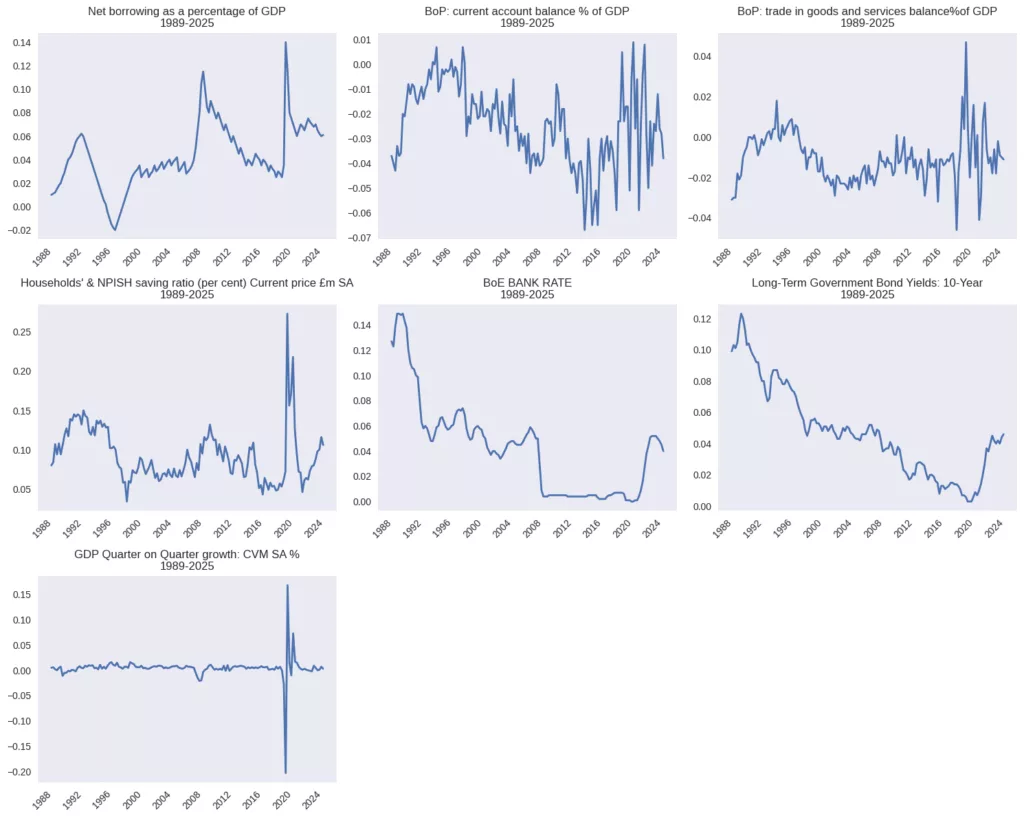

On the Balance of Payment side, the UK’s goods trade deficit widened slightly to £21,18 bln in August, as the economic engine requires import inputs. Our model’s estimate is for an average £24.4 bln Balance of Payment trade deficit, meaning a 3% to 2,9% current account deficit to GDP for the year, t&c applies.

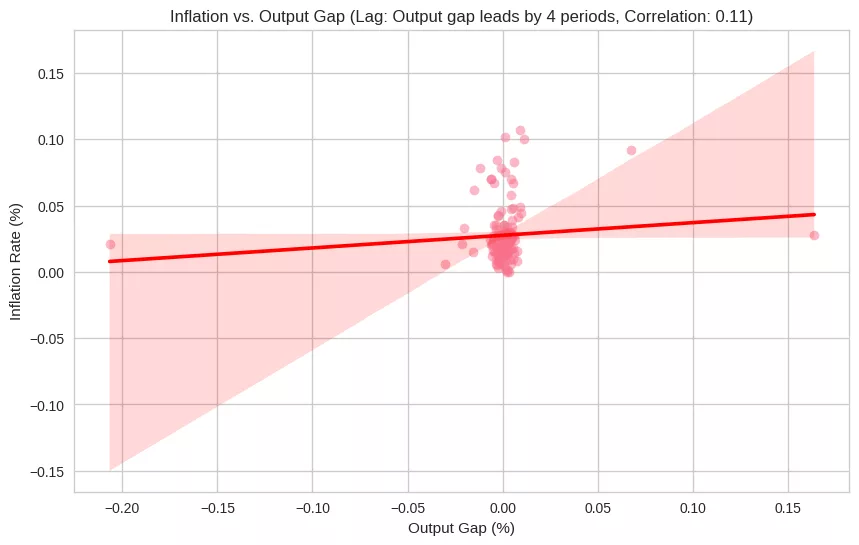

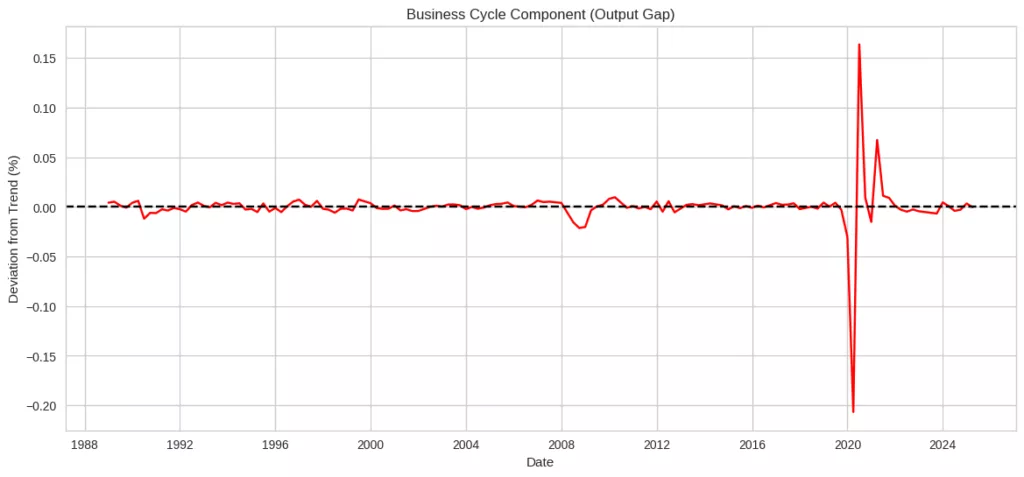

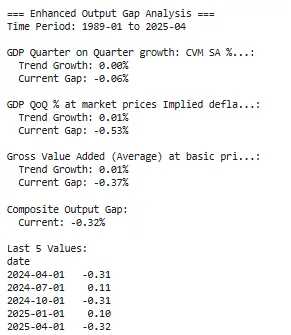

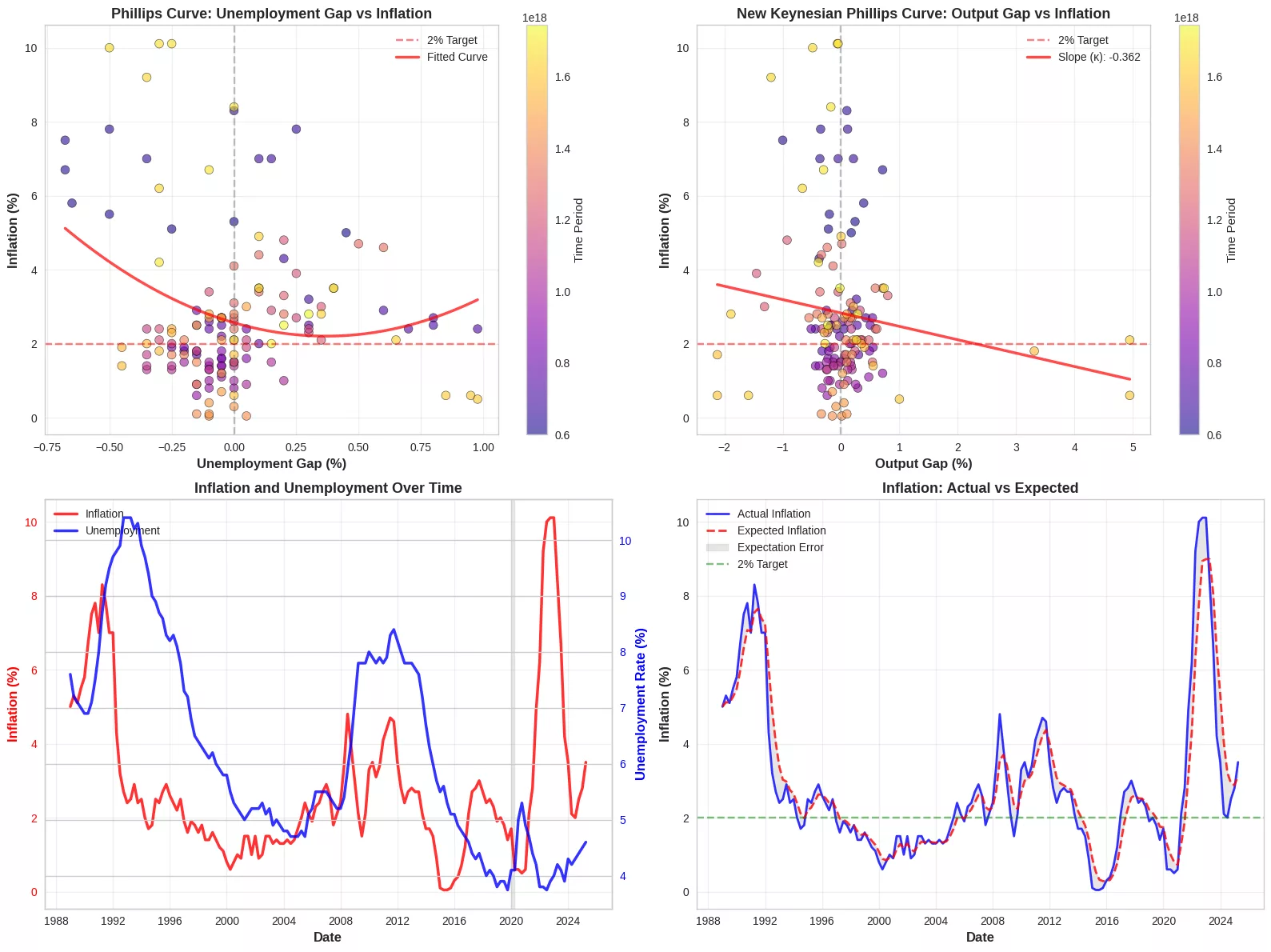

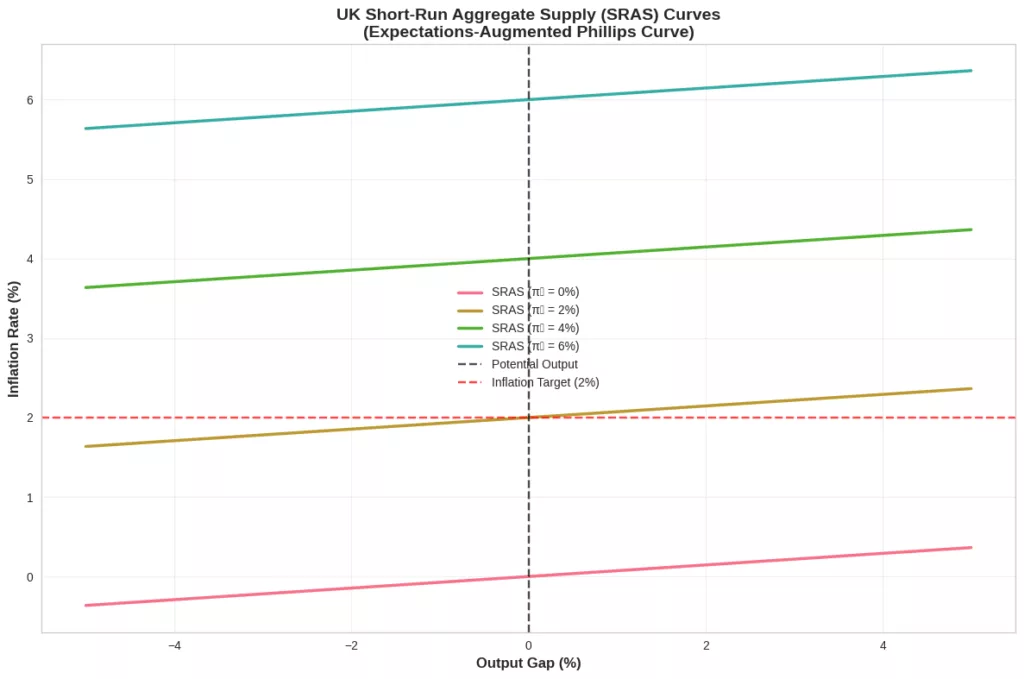

The UK Output Gap Conundrum

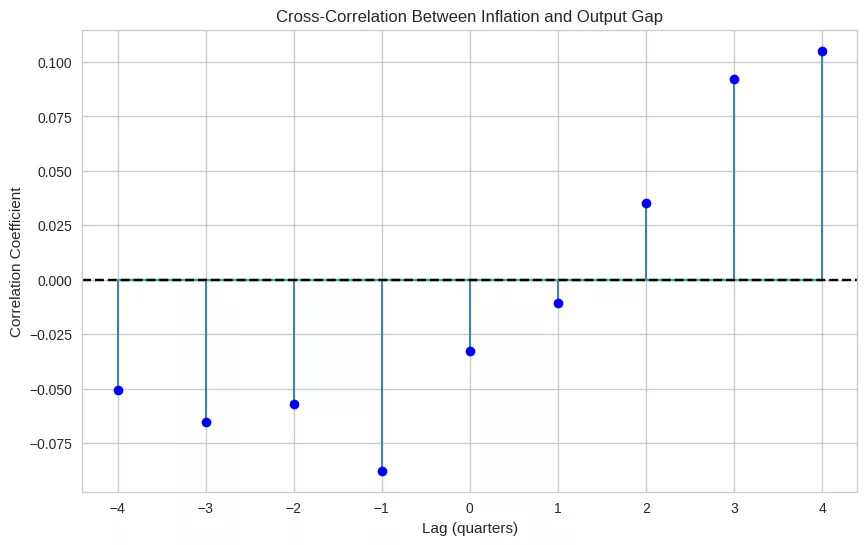

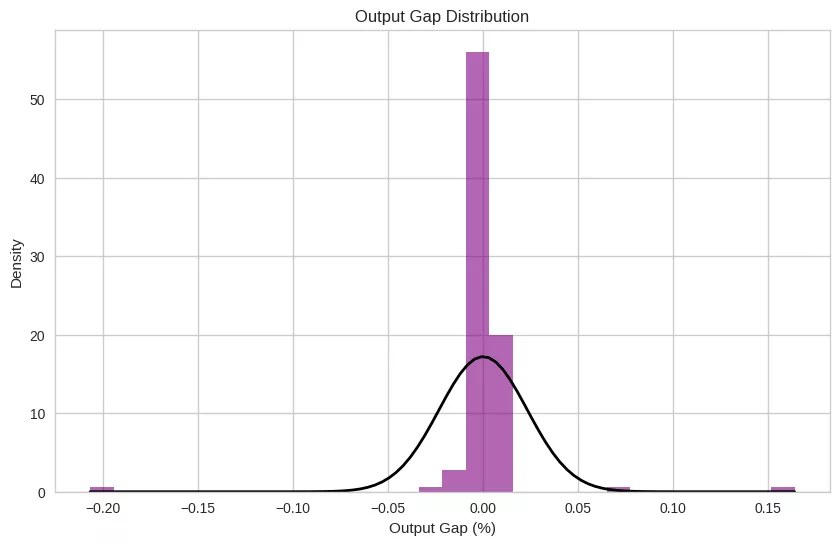

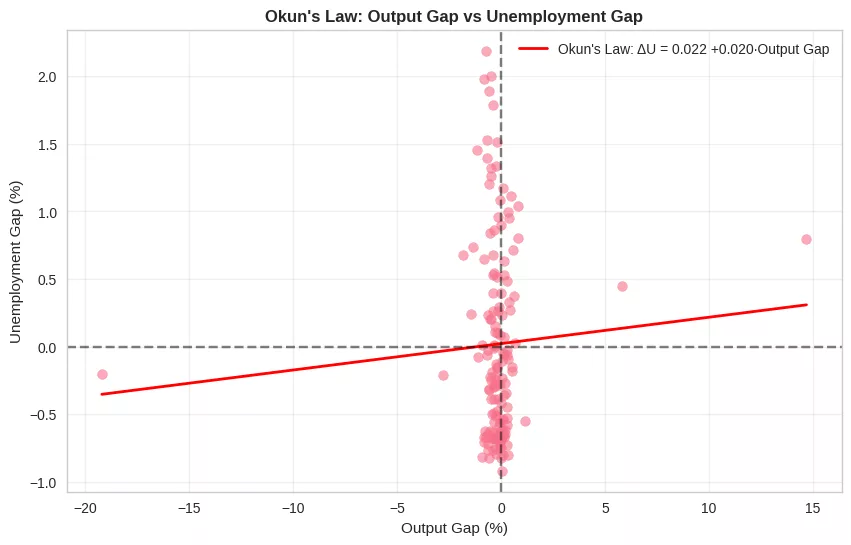

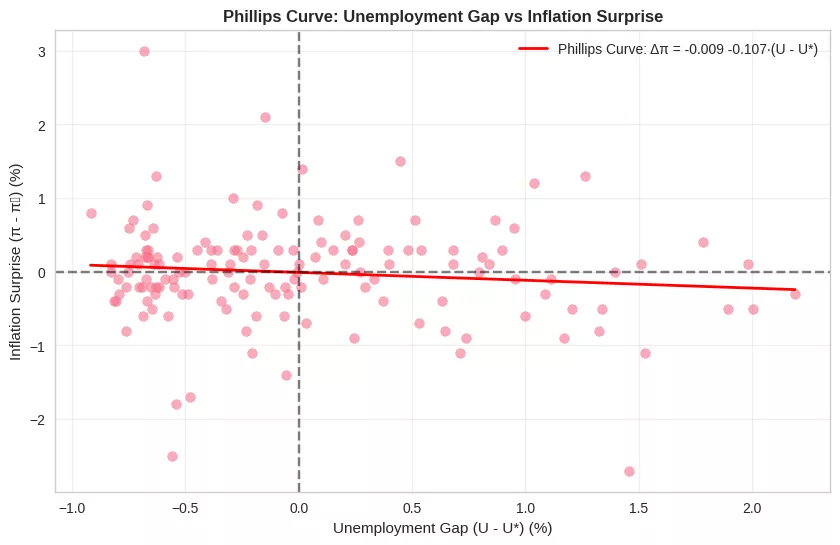

Our models bring to light one of the underlying structural issue of the UK, hence, a flat to slightly negative output gap, correlated with sticky inflation and the inability of large corporate and SMEs to deal with factors and input costs, hence the price adjustments are prolonged and sticky, making inflationary pressures and dynamics more persistent (coefficient 0.543), which make the overall growth picture of stagflationary slow growth, that is not unusual among advanced economies which are reliant mostly on services and consumer demand. What had been determined with modelling it’s that a positive output gap helps in decreasing Inflation (coefficiente -0.010), considering also the observed post-GFC phenomena of the break-down of the Phillips Curve, in our data the maximum correlation between output gap and inflation is only 0.11 (when output gap leads by 4 quarters), and the contemporaneous correlation is essentially zero (-0.035).

Although moderate economic growth, quarter-on-quarter, The UK economy faces a productivity stagnation crisis with broken traditional relationships, while inflation has been sticky and higher between 3.5% to 4.4%, which masks deeper structural problems: a flat Phillips Curve, weak productivity growth, and an economy operating below potential despite fiscal stimulus. Our model of Short-Run-Aggregate-Supply helps explain how the Inflation Persistence coefficient 0.543, links the inflationary spiral to a buildup of inflation expectations from the services industry, through real estate, SMEs businesses and consumers, as an empirical determinant factor of the Phillips Curve signal breakdown. In this framework, the Exchequer Fiscal Stimulus alone doesn’t have the ability to generate enough supply-side aggregate output, at least in the short-term, that can be the shuttle-cock that accelerates the aggregate supply dynamics, also considering a wider global economic slowdown in aggregate output and growth.

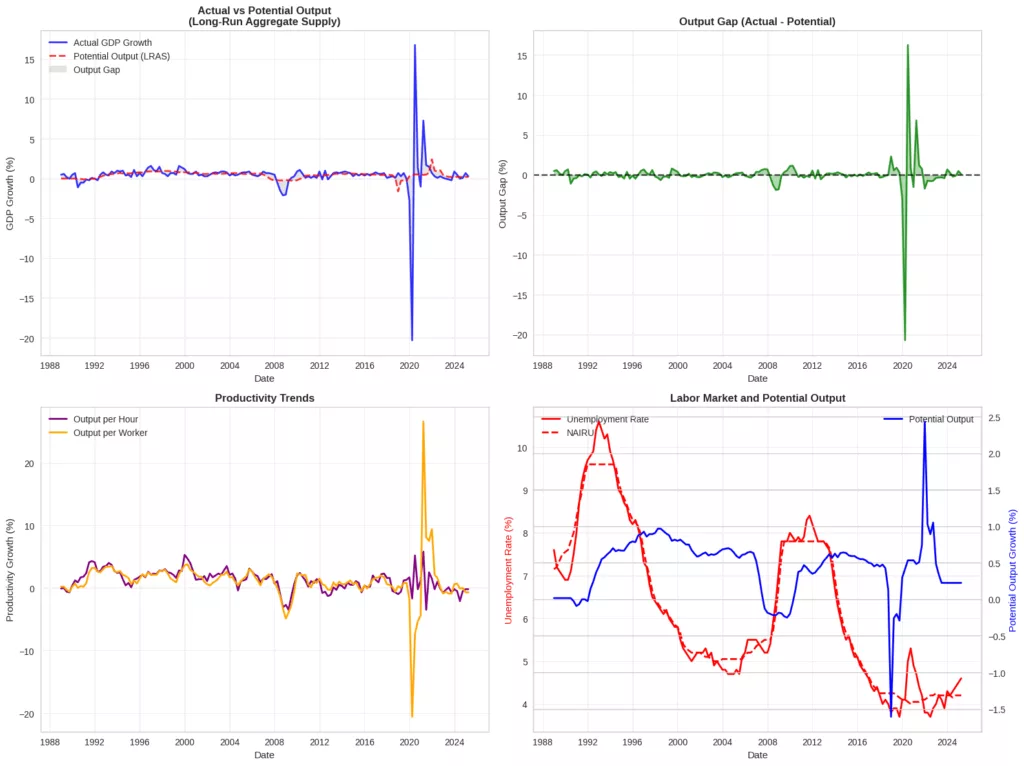

The UK business cycle output gap chart and the output gap histogram distribution provide empirical evidence of a flat as a pancake, slightly negative output gap. Here we have the latest empirical results:

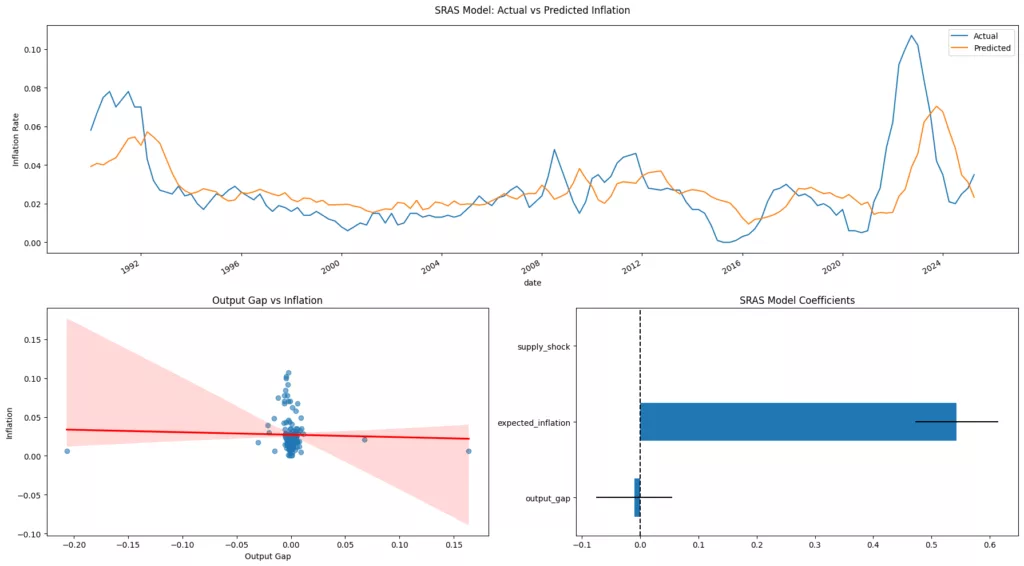

As we can see from the charts, the UK output gap, hence the strength and dynamic of its economic growth have been pretty much flat and slightly negative for many quarters, seemingly close to potential output, although we can also see how the Short-Run-Aggregate-Supply chart shows how actual inflationary pressures in the UK are higher than the model would otherwise suggest, that meaning a flat output gap, generates inflation, or otherwise, even with slow growth, the economy overheats with higher inflation dynamics, which consistently point to stagflationary economic growth. Considering, as mentioned, the observed post-GFC phenomenon of the Phillips Curve dynamics breakdown, policy makers and technicians find it difficult to respond to similar economic dynamics, as defined by the same Rachel Reeves, as ” the economy seems to be feeling stuck”. Otherwise, empirical models confirm how, what seems a subjective perception, can be convalidated by the actual data of persistent inflationary and inputs costs, within a moderate and low economic growth output, and these are dynamics not easily explained by standalone traditional wage-price spirals, but as other major advanced economies, would be reasonable to find empirical evidences of a long-term built up of inflationary assets bubble in parts of the economy, such as real estate and services industry, that in turn generate the dynamics of inflation expectations in the economy, so that withstanding, lower growth, Inflation expectations tend to steadly increase. The stagflationary dynamics are also evident with the rising unemployment rate of 4.8%, in our estimates UK unemployment rate will rise to 5% | 5.5% range, while otherwise the Exchequer Fiscal stimulus of trying to spur investment, will take time to become an uplift in output growth and aggregate supply, as there are no short-term fixes, but only long term structural investments.

What to Fiscally Expect and Where Does the Fiscal Purse Stand

In the near to medium term, the VAR Model provides a macro-picture of the economy, where the CPI Annual Rate of Inflation is expected to peak in the coming quarters, as a lagged effect of the rising unemployment rate, and the labour market slack opening up, consistent with a flat as a pancacke output gap. Unemployment rate is forecast to increase to 5.1% in the coming quarters, CPI to stand around 3.6%, while the Bank of England, depending on the inflationary picture, could try to decrease the bank rate below 4%. The economic picture in the near to medium term is of an economy shifting from higher and persistent inflation towards the BoE price stability aim, while the needs of balancing the budget and fiscal prudence would have to be proven so that inflation expectations and the yield curve risk-premium could eventually be priced toward the downward path, hence the job of the Exchequer would be also of communicating and managing inflation expectations, either for businesses and for taxpayers, that isn’t a small task, as exogenous factors, such as a more benign, global geopolitical backdrop could eventually provide the cooling factor of managing inflation expectations going forward. In so far, the UK macro-economic and fiscal picture isn’t so different, nor better or worse, that any other major advanced economy, there are idiosyncratic structural features that would require adjustment and wholesale restructuring, such as the managing, composition and duration of the outstanding stock of public debt, coupled with a wider more progressive reframing of the income tax brackets and the system of social security contribution, but these never seemed to be the line of thoughts neither the priorities of any Westminster Government, thereby, we can only take stock of the ongoing Fiscal picture and the empirical data.

Our estimates with ONS data see the net borrowing to GDP at around 6%, the latest data from the ONS show provisional figures of £ 149 bln, equivalent to 5.1% of GDP, considering also the Balance of Payment to Primary Account ratio stands around 3% deficit. The UK economy, as well as France, has to grapple with higher Fiscal deficits and the requests of more welfare state spending and infrastructure investments, in a bond market and money market environment of higher borrowing rates and rising yield curve term structure, as debt servicing, particularly debt servicing linked to RPI inflation premium, is the heaviest inflating brunt on the balance sheet.

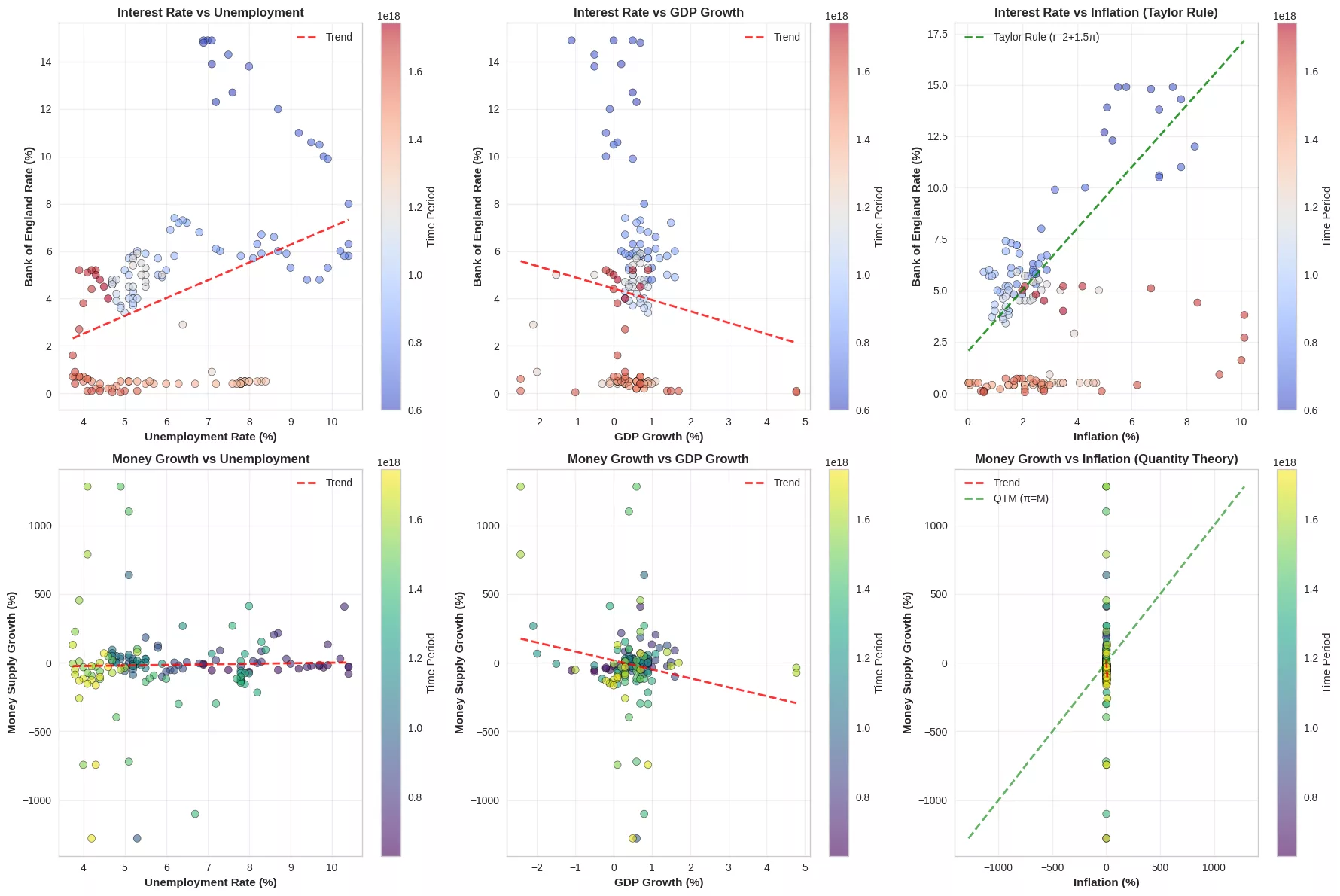

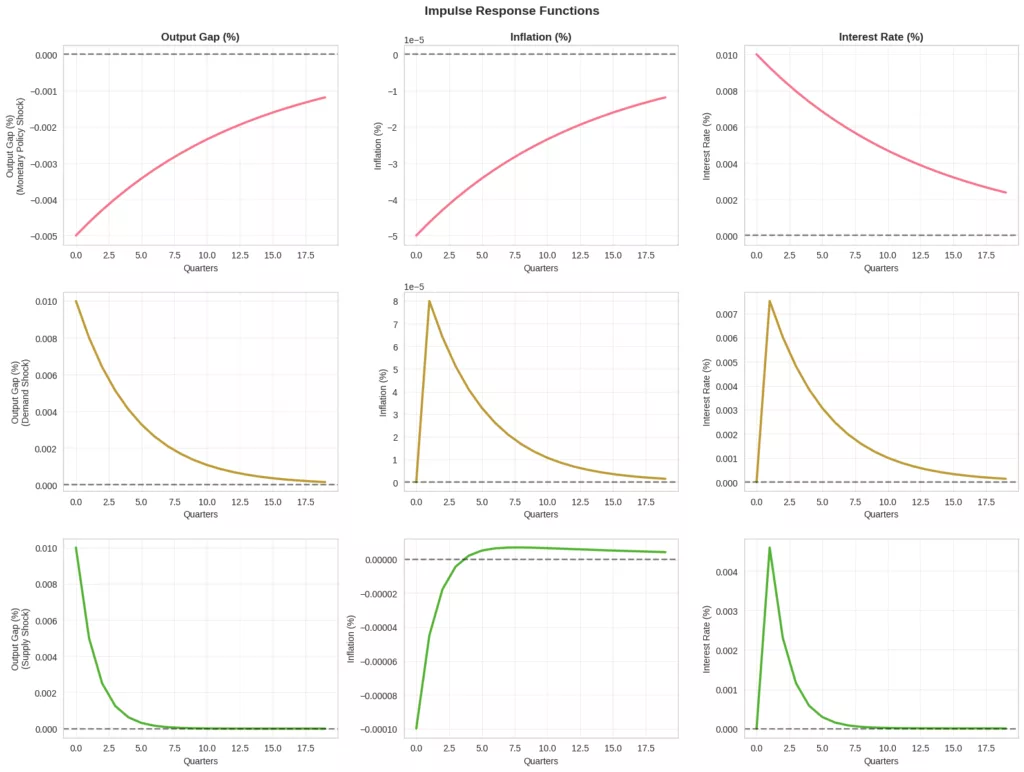

Comprehensive analysis of UK macroeconomic data

Based on a comprehensive analysis of UK macroeconomic data quarter-on-quarter from 1989 to 2025, the UK economy demonstrates a complex interplay of near-equilibrium current conditions alongside challenging structural dynamics. Our model estimation identifies a monetary policy framework with significant interest rate persistence (ρ_r = 0.927) and a balanced approach to inflation targeting (φ_π = 1.10) and output stabilisation (φ_y = 0.9296), while the substantial price rigidity (θ_p = 0.6089) indicates firms update prices approximately every 2.5 quarters on average. The model fit shows excellent performance for the Taylor Rule (RMSE: 0.5829) but challenges in the Phillips Curve equation (RMSE: 174.51), suggesting traditional inflation-output relationships may be misspecified. This is further illuminated by the New Keynesian Phillips Curve analysis, where the Gamma NKPC specification—incorporating marginal costs from wages and import prices—demonstrates superior performance (AIC: 106.98, BIC: 121.55) over both Classic and Hybrid versions, revealing nearly balanced forward and backward-looking inflation expectations (γ_f = 0.4808, γ_b = 0.4332) with significant real wage effects (δ_w = -0.0998). The structural parameter estimates, including a high discount factor (β = 0.9500-0.9869 across models) and moderate risk aversion (σ = 0.5000), paint a picture of a patient consumer base with significant forward-looking behaviour. These results occur within a macroeconomic context of average inflation (3.6%) but substantial volatility (σ=2.13%), combined with modest GDP growth (0.49%), suggesting the UK economy operates with flattened Phillips Curve relationships where traditional demand management policies have diminished effectiveness, requiring instead a sophisticated policy mix that addresses both inflation expectations through credible monetary frameworks and structural constraints through supply-side enhancements, particularly given the significant role of cost-push factors and imported inflation in the current elevated inflation environment.

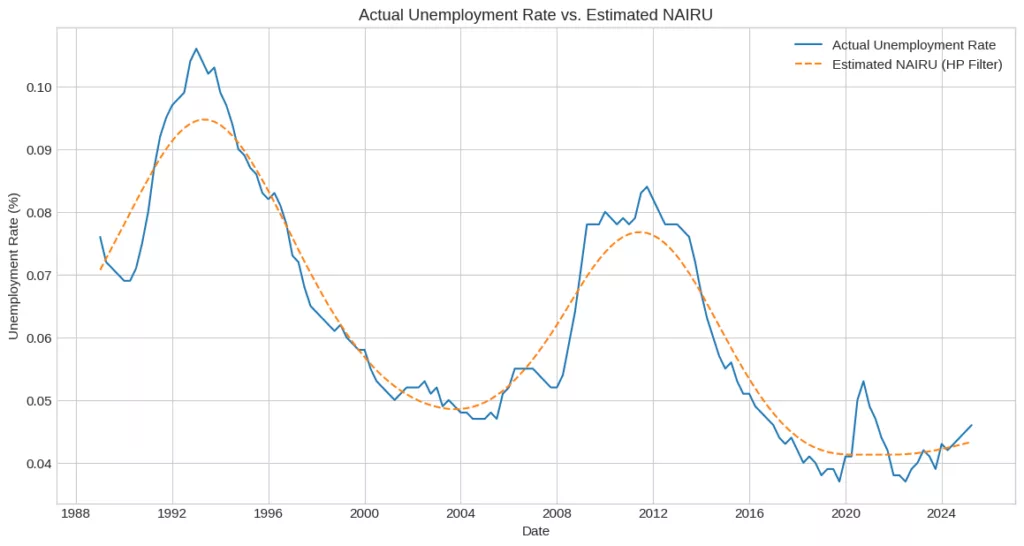

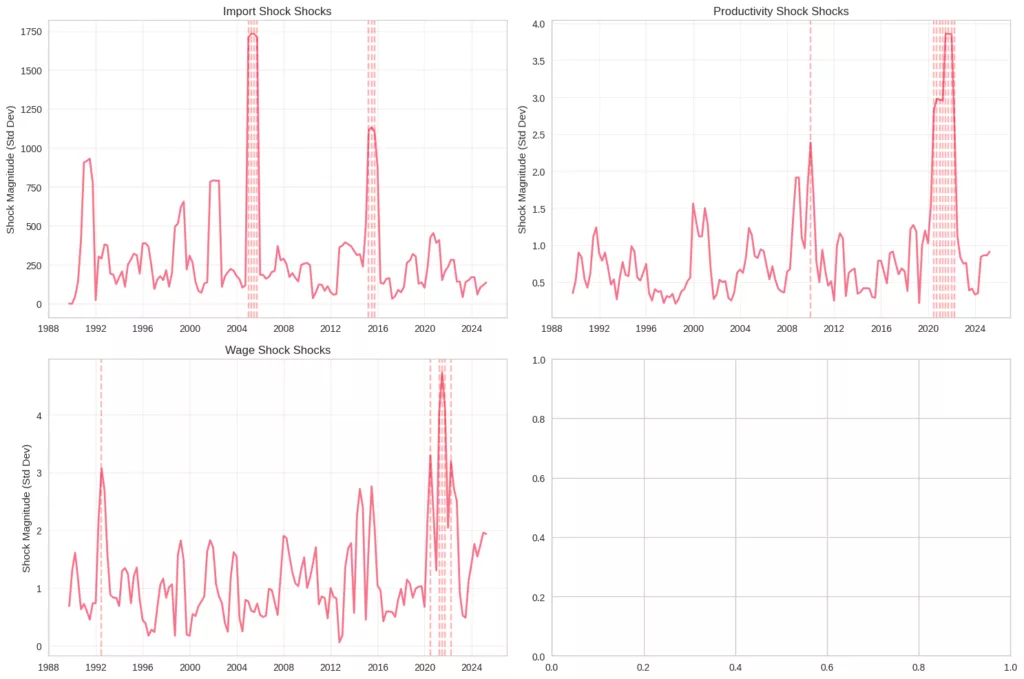

Indeed, with a complete Aggregate Supply and Aggregate Demand econometric model of the UK’s current economic landscape reveals a complex and challenging environment characterised by the paradoxical coexistence of modest positive output gaps and persistently elevated inflation, against a backdrop of significantly weakened structural relationships and concerning supply-side constraints. The UK economy currently operates slightly above its sustainable capacity, with a flat output gap and unemployment at 4.8% resting below the estimated NAIRU of 4.2%, yet inflation remains stubbornly high at 3.5%, well above the 2% target. This apparent contradiction is explained by the dramatically flattened short-run Phillips curve, evidenced by an exceptionally weak slope parameter (β = 0.0728), indicating that traditional inflation-output gap tradeoffs have largely broken down, and demand management policies now yield diminishing returns for price stability. Compounding this challenge, the long-run aggregate supply picture reveals an alarming secular stagnation, with potential growth averaging only 0.45% annually, a rate insufficient for meaningful improvements in living standards, while the economy has experienced 22 major supply shocks since 1989, primarily driven by import price volatility and productivity disruptions, creating persistent inflationary pressures that monetary policy struggles to contain. The superior-performing Gamma NKPC specification further illuminates these dynamics, showing that UK inflation is now best explained through balanced forward and backward-looking expectations (γ_f = 0.4808, γ_b = 0.4332) combined with significant real wage effects (δ_w = -0.0998) and a steeper marginal cost channel (κ = 0.1261), suggesting that cost-push factors and inflation expectations have become more dominant drivers than output gaps. Within this context, the enhanced DSGE model parameters reveal a monetary policy approach characterised by high persistence (ρ_r = 0.927) with moderate inflation targeting (φ_π = 1.10) and active output stabilisation (φ_y = 0.9296), operating alongside substantial price rigidity (θ_p = 0.6089) that slows economic adjustments. The fundamental policy implication is clear: the UK faces a structural rather than cyclical challenge, requiring a fundamental reorientation toward supply-side enhancements—including productivity-enhancing technologies, labor market flexibility improvements, and regulatory reforms—to expand the economy’s productive capacity beyond the current anemic 0.45% trend growth, while monetary policy must carefully navigate the flattened Phillips curve by maintaining a neutral stance that acknowledges the limited anti-inflationary benefits of demand contraction yet remains vigilant against inflation expectations becoming unanchored in this fragile equilibrium.

The identification of 22 major supply shock periods, comprising 7 import shocks, 9 productivity shocks, and 6 wage shocks, reveals a pattern of recurrent economic disruptions that have fundamentally shaped the UK’s inflationary environment and policy challenges. These supply shocks, visualized through their standardized magnitude over time, demonstrate that the UK economy has been particularly vulnerable to external price pressures and domestic productivity constraints, with import shocks typically correlating with global commodity price fluctuations and exchange rate volatility, productivity shocks reflecting the UK’s structural challenges in maintaining consistent efficiency growth, and wage shocks emerging from labor market tightness and bargaining dynamics. The persistence of these shocks, often lasting 2-4 quarters with significant pass-through to inflation, has contributed to the elevated and volatile inflation environment (averaging 3.2% with σ=2.13%) despite generally modest economic growth (0.49% average GDP growth). The current economic situation of elevated inflation (3.8%) alongside only modest output gaps suggests that recent supply shocks may be lingering in the system, requiring a sophisticated policy response that addresses both the immediate inflationary pressures through careful monetary policy calibration (acknowledging the high persistence ρ_r=0.927 and moderate inflation targeting φ_π=1.10 from DSGE estimates) and the underlying structural vulnerabilities through supply-side enhancements that build resilience against future shocks while expanding the economy’s productive capacity beyond the current anemic trend growth rate.

UK Nairu and Output Gap dynamics modelling

Based on the comprehensive UK NAIRU and output gap modelling analysis spanning 1989-2025, the current economic situation presents a nuanced picture of an economy operating remarkably close to its structural equilibrium yet experiencing persistent inflationary pressures that challenge conventional macroeconomic relationships. The consensus estimates reveal an output gap of -0.159%, indicating the economy is operating essentially at its potential capacity, while the unemployment rate sits just 0.262% above the estimated NAIRU of 4.338%, suggesting a labour market near its natural equilibrium. However, the persistence of elevated inflation at 3.50% amidst these near-equilibrium conditions underscores the breakdown of traditional economic relationships, as evidenced by the exceptionally weak Okun’s Law coefficient (-0.0195) with statistically insignificant explanatory power (R²=0.0033, p-value=0.4932) and a relatively flat Phillips Curve slope (0.1065) that also lacks strong statistical significance (p-value=0.1853). This disconnection between conventional gap measures and inflation dynamics suggests that the UK economy is experiencing structural transformations where output and unemployment gaps have diminished predictive power for price pressures, potentially due to globalisation effects, changing inflation expectations formation, or supply-side constraints that are not fully captured in traditional gap measurements. The robustness of these findings is strengthened by the multiple estimation methodologies employed, which show remarkable consistency in NAIRU estimates (ranging from 4.250% to 4.346%) and general agreement on the direction of output gaps despite methodological differences. The policy implications clearly point toward a neutral stance given the economy’s proximity to its estimated potential, but the elevated inflation despite these equilibrium conditions suggests that policymakers must look beyond traditional gap analysis to address the underlying structural factors—including potential productivity weaknesses, supply chain vulnerabilities, or inflation expectations dynamics—that are sustaining price pressures in an economy that otherwise appears to be operating near its sustainable capacity.

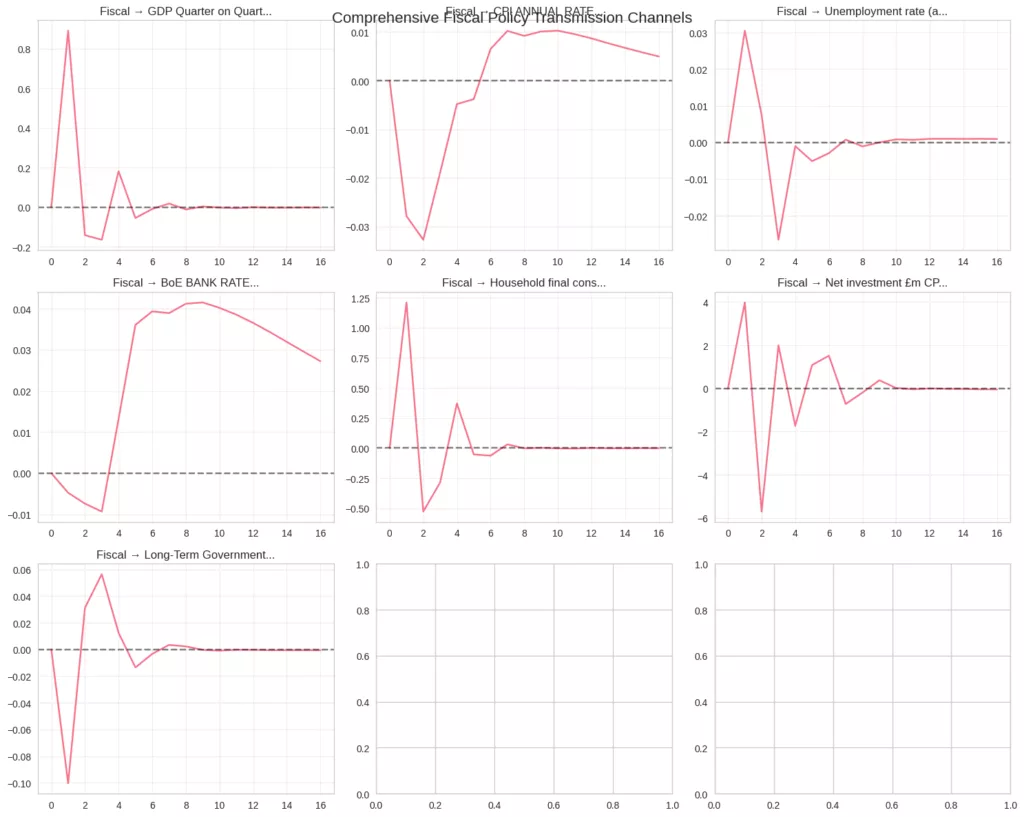

UK Fiscal SVAR and Blanchard’s Structural VAR data reveal a negative Fiscal Multiplier Conundrum

A comprehensive UK Fiscal SVAR analysis employing Blanchard’s structural VAR methodology results reveal a complex fiscal transmission mechanism characterised by a surprisingly negative fiscal multiplier of -0.0533, suggesting that fiscal expansions in the UK context may have contractionary effects in the medium term, potentially due to crowding-out effects, Ricardian equivalence behaviour, or monetary policy offsetting actions. The core Blanchard SVAR identified six key stationary variables: GDP growth, CPI inflation, Bank Rate, and first-differenced unemployment, fiscal balance, and current account, with optimal lag length selection criteria indicating substantial persistence in fiscal transmission (5-8 quarter effects). The model results show intricate contemporaneous relationships, particularly strong direct effects from GDP shocks to other variables and significant inflation responses to multiple shocks, while the sectoral SVAR analyses confirm robust transmission mechanisms across fiscal-monetary, inflation-unemployment, and external-growth dimensions. The negative fiscal multiplier, combined with the structural identification showing complex dynamics between fiscal policy, monetary conditions, and external balances, suggests that traditional Keynesian fiscal stimulus may be less effective in the UK’s open economy with independent monetary policy, requiring a carefully calibrated policy mix that considers the offsetting effects of exchange rate movements, interest rate responses, and private sector reactions. These findings have profound implications for fiscal policy design, emphasising the need for sustainable public finances, coordination with monetary authorities, and structural reforms that enhance fiscal policy effectiveness rather than relying solely on discretionary fiscal measures for macroeconomic stabilisation.

Why More Fiscal Expansion Could Risk of Being Contractionary for the UK Economy

the British economy currently operates in a precarious equilibrium characterized by conflicting signals: while output gaps hover near zero (-0.16%) and unemployment rests just above structural levels (4.60% vs NAIRU of 4.34%), suggesting the economy is at capacity, inflation remains stubbornly elevated at 3.50% alongside a surprisingly negative fiscal multiplier (-0.053) and dramatically flattened Phillips Curve (slope: 0.07-0.11). This paradoxical combination—near-potential output with persistent inflation—indicates deep structural challenges that transcend traditional demand management solutions, including weak productivity growth (0.45% potential output growth), recurrent supply shocks (22 identified episodes), and broken historical relationships (statistically insignificant Okun’s Law). For the upcoming budget, we should therefore expect a nuanced approach that maintains fiscal neutrality given the economy’s proximity to capacity while aggressively pursuing supply-side enhancements: targeted investments in productivity-enhancing technologies, labour market reforms to improve skills matching and reduce structural unemployment, regulatory simplification to boost competition, and infrastructure upgrades to expand productive capacity. The budget likely will avoid traditional fiscal stimulus, given the negative multiplier effects and instead focus on structural reforms aimed at raising the economy’s speed limit while using careful calibration to avoid exacerbating current inflationary pressures, representing a pivotal shift from cyclical management to structural improvement in the UK’s economic fundamentals.

“This article is part of the Capital Market Journal Working Paper Series. All content, analysis, and conclusions presented herein are the intellectual property of the Capital Market Journal, its editors, and publishers. Any reproduction, distribution, or citation by third parties—in whole or in part—without prior written consent is strictly prohibited and constitutes a violation of copyright law. “