From the earliest days of human thought, philosophers have wrestled with the fundamental questions of existence: What does it mean to live? What defines our purpose? Why, despite moments of happiness and triumph, do we seem to suffer and struggle endlessly? For many, the answer lies in the tragic nature of human existence—a condition rooted in our limitations, our illusions of freedom, and our existential confrontation with meaninglessness.

Ancient Greek Philosophy: Limit (kata metron) and the Cycle of Life

In ancient Greek philosophy, the concept of kata metron (limit) plays a central role in understanding the human condition. The Greeks believed in a cosmic order where everything had its place and limit, governed by divine principles. Kata metron signifies living in accordance with natural boundaries, suggesting that life is finite, bound by the cycles of nature and human biology: birth, growth, marriage, procreation, senility, and death. This idea aligns with the notion that life is inherently tragic because it is marked by limits—both physical and existential. Humans, as part of nature, are subject to the same processes of deterioration and death that govern all living things. The philosophy of Heraclitus echoes this view, emphasizing the inevitability of change and the flux that governs existence: “All things flow” (πάντα ῥεῖ). Life is not static; it is an ongoing process of becoming and perishing, creating a sense of instability. The tragedy, according to Heraclitus, lies in the inherent conflict between our desire for permanence and the reality of change.

Aristotle extended this by describing human existence as a balancing act between opposing forces. For Aristotle, human beings must constantly seek “εὐδαιμονία” eudaimonia (flourishing or well-being) through virtuous living, yet this quest is constrained by our finitude. The tragic hero in Greek drama, exemplified in Sophocles’ Oedipus, faces overwhelming forces—fate, the gods, or personal hubris—only to find that their aspirations are thwarted by inescapable limits, leading to suffering and often ruin. Thus, ancient Greek philosophy positions human existence as tragic because we are bound by natural and social forces beyond our control. In addition to anthropos (meaning “human” or “man”), the ancient Greeks had another term to describe human beings: Tzanatos, or “the mortal one.” This designation underscores the Greeks’ deep awareness of life’s inherent impermanence and the inescapable fate of death. To the Greeks, mortality was not a mere biological fact, but a defining characteristic of human existence. They recognized that humans, unlike the gods, are bound by the natural cycle of life and death, subject to forces beyond their control. This understanding is woven into their mythology, philosophy, and literature. For example, in the epic of Homer and the tragedies of Aeschylus and Sophocles, human beings are constantly reminded of their mortality—often referred to as “θνήτος” Thnetos, “the one who dies”—and their limited time on earth. The term “Θάνατος” Thanatos signifies this tragic knowledge, that all who live must eventually die, completing the cycle of birth, growth, decline, and death. In this sense, the Greeks viewed mortality not as a tragedy to be feared, but as an essential aspect of the human condition, one that shapes the entire arc of a person’s life. Life is thus tragic because it is fleeting, a brief interruption in the vast, eternal flow of nature.

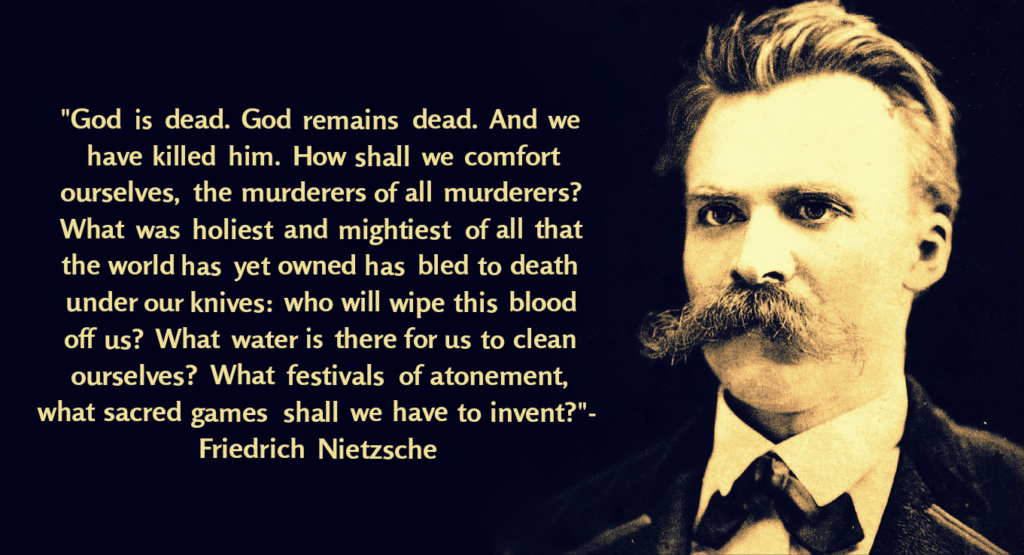

Religion, across various cultures, has often provided a framework for understanding human existence and mortality, but in doing so, it has also created what many philosophers argue is an illusion of freedom and existence beyond life. From ancient civilizations to modern religious beliefs, the promise of an afterlife—whether it be eternal salvation, reincarnation, or transcendence—offers solace to individuals facing the inevitability of death. This religious narrative suggests that human existence extends beyond the natural cycle of birth, growth, and death, into an eternal realm where suffering ceases, and meaning is fully realized. Christianity, for example, teaches that believers are freed from the bondage of sin and death through salvation, offering the promise of eternal life with God. Plato’s concept of the immortality of the soul similarly posits that the soul escapes the limitations of the body, rising to a higher, eternal realm of truth and perfection. However, philosophers like Nietzsche and Sartre have critiqued this religious worldview, arguing that it perpetuates an illusion that distracts people from confronting the realities of their mortal existence. Nietzsche famously declared that “God is dead”

symbolizing the collapse of these religious constructs that once provided meaning to life. In his view, religion prevents individuals from embracing the tragic and finite nature of life, instead fostering a passive acceptance of suffering with the false hope of redemption in another world. Sartre goes further, asserting that the belief in an afterlife or divine plan is a form of bad faith, a self-deception that allows people to avoid the anguish of freedom by clinging to preordained purposes or external sources of meaning. In reality, Sartre argues, humans are left to confront their mortality and create meaning within the confines of this life, without the illusion of existence beyond death.

Paul of Tarsus and the Religious Illusion of Eternal Life

In the Acts of the Apostles in the New Testament, there is an account of Paul of Tarsus (Paolo di Tarso) travelling to Athens to preach the message of Christianity, particularly the belief in life after death through resurrection. Paul stood in the Areopagus, the intellectual heart of Athens, where philosophers, particularly Epicureans and Stoics, gathered to discuss ideas. Paul’s message was discerned by the Stoics even derision. When he spoke about the resurrection of the dead and the existence of his God, many Athenians laughed at him, asking, “Where is your God?” They found his claim absurd, as it contrasted sharply with their own beliefs about life, death, and the cosmos. For the Greeks, particularly in the philosophical tradition, death was understood as a natural part of the human condition, as part of the inevitable cycle of life—birth, growth, and death. The materialist schools, such as Epicureanism, saw death as the end of consciousness, with no life beyond the grave. Even for the Stoics, while they believed in a rational order to the universe, the idea of personal immortality or bodily resurrection seemed foreign and unlikely.

The Athenians’ laughter at Paul was not just a rejection of his specific religious claim but a reflection of their broader philosophical worldview. The notion of resurrection, which was central to Paul’s teaching, clashed with their understanding of death as the final end, with no divine intervention beyond that. The Greeks had developed a profound understanding of mortality, embodied in their term “Θάνατος” Thanatos, for they accepted that human beings are mortal and subject to the unchangeable cycle of life.

Friedrich Nietzsche later recalls this rejection of resurrection in his critique of Christianity. In his works, Nietzsche argued that Religion’s promise of life after death is an illusion that diminishes life on Earth. For Nietzsche, the Greeks, particularly in their tragic literature and philosophy, had a heroic acceptance of death and the limits of life, which he admired. In this sense, the Greek derision of Paul symbolizes a profound cultural clash: while Paul offered hope through faith in the resurrection, the Greeks embodied the tragic awareness of life’s finitude and the strength to face it without the need for a metaphysical crutch. Nietzsche viewed the Greek attitude toward life and death as more authentic and life-affirming than what he saw as the life-denying doctrines of Christianity.

Shakespeare’s theatrical representation of mankind’s tragic condition

The themes of existentialism and the tragic nature of human existence are not only prevalent in philosophy but also permeate the world of literature and theatre. One of the most profound explorations of these themes can be found in the works of William Shakespeare, whose plays often grapple with the core questions of existence, mortality, and meaning. In particular, Hamlet, arguably Shakespeare’s most existential work, embodies the tragic human condition. In the famous soliloquy “To be or not to be, that is the question”, Hamlet contemplates the pain and uncertainty of life, questioning whether it is nobler to endure suffering or to end it all, thereby acknowledging the futility of existence and the unknown beyond death.

Hamlet’s internal struggle reflects existential concerns about the absurdity of life, as he oscillates between action and inaction, caught in a world that appears chaotic and devoid of meaning. This is reminiscent of Sartre’s notion of “anguish”, where the individual must confront the weight of freedom and the lack of inherent purpose, leading to a deep sense of despair. Hamlet’s recognition that “the rest is silence” at the play’s conclusion mirrors the nihilism of Nietzsche, where the individual, upon confronting death and the collapse of metaphysical certainties, realizes that existence is a void into which we are thrust without divine guidance or ultimate truth.

Similarly, Macbeth deals with the fleeting and tragic nature of life. In his soliloquy, “Life’s but a walking shadow, a poor player that struts and frets his hour upon the stage and then is heard no more,” Macbeth reflects on the insignificance and temporality of human existence. His recognition that life is “a tale told by an idiot, full of sound and fury, signifying nothing” echoes existentialist ideas about the absurdity of life, where human efforts and ambitions are ultimately futile in the face of inevitable death. Shakespeare, like existentialist philosophers, presents a world in which humans struggle to find meaning within a framework of chaos, uncertainty, and mortality, ultimately facing the tragic reality of their own limitations.

The advent of Enlightenment an era of reason collides with the constraints of human nature

Immanuel Kant’s philosophical exploration of freedom is deeply intertwined with his critique of the Enlightenment and the notion of human autonomy. Kant heralded the Enlightenment as an era of reason, where individuals were encouraged to think for themselves rather than rely on tradition, authority, or dogma. He famously declared, “Sapere aude!” (“Dare to know!”), urging people to use reason as a tool for understanding the world and their place within it.

However, while Kant celebrated the potential of the Enlightenment to empower individuals, he also acknowledged the inherent limitations that come with it. Kant’s conception of genuine freedom involves acting according to one’s rational will and moral law, guided by the Categorical Imperative, which dictates that one should act only according to that maxim by which they can at the same time will that it should become a universal law. In this framework, true freedom is not simply the absence of constraints; it requires the capacity to make moral decisions based on rationality rather than mere impulse or societal expectations. Despite this ideal, Kant recognized that individuals are often constrained by their human nature. He observed that passions and desires can lead people astray from moral reasoning, trapping them in a state of heteronomy, where their actions are governed by external influences rather than their own rational will. Kant argued that such inclinations could create an illusion of freedom, where individuals believe they are acting freely when, in fact, they are merely responding to their desires or societal pressures. In addition, Kant highlighted the role of social conditions and cultural norms that shape moral understanding. While the Enlightenment emphasized individual reasoning, it also produced a landscape of competing moral frameworks, leading to a form of moral relativism. In this context, individuals may feel free to make choices, but those choices are often dictated by prevailing societal standards, thereby undermining true autonomy. Kant argued that without a universal moral law grounded in reason, individuals might fall into the trap of conforming to social norms, believing they are exercising their freedom when they are actually surrendering it. Kant’s critique of the Enlightenment includes the warning that an overemphasis on individualism could lead to a fragmented understanding of moral obligation. He believed that while the Enlightenment aimed to liberate humanity from the shackles of ignorance, it could inadvertently foster a kind of moral chaos, where the absence of a shared moral framework leaves individuals adrift in a sea of conflicting desires and values.

In essence, Kant’s philosophy reveals the paradox of the Enlightenment: while it promotes the idea of human freedom and autonomy through reason, it also exposes the limitations imposed by human nature and social conditions. Genuine freedom, for Kant, requires a continuous struggle to align one’s desires with rational moral law, thereby transcending the illusions of autonomy fostered by unchecked passions and cultural norms. Ultimately, Kant calls for a more profound understanding of freedom—one that embraces the rational basis of moral duty and recognizes the complexities of human existence in the pursuit of true autonomy.

Rousseau’s Social Contract and The Illusion of Freedom

Jean-Jacques Rousseau famously articulated the paradox of modern society in his work “The Social Contract” with the statement, “Man is born free, and everywhere he is in chains.” This phrase captures the tension between the natural freedom humans are born with and the social and political constraints that bind them as they enter organized societies. While Rousseau believed that in the state of nature, humans were free, uncorrupted, and self-sufficient, he argued that the development of civilization—particularly in the context of capitalism and private property—had led to widespread alienation and inequality. Rousseau’s critique of modern society focuses on how the rise of private property became the root of inequality and the ultimate cause of human alienation. He posits that the formation of bourgeois society—where the ruling class, or bourgeoisie, controls economic resources—was a deliberate act of deception. According to Rousseau, early humans lived in a more egalitarian state, but with the introduction of property rights, the wealthy few managed to appropriate the majority of resources, laying the groundwork for class division and exploitation. He argues that private property led to the establishment of laws and governments that were designed not to protect the liberty of all, but to maintain the status quo that favoured the wealthy and powerful. Rousseau observed that in modern capitalist societies, freedom is an illusion. The bourgeoisie, through their control of economic resources and institutions, created a system where individuals are alienated from their true selves and from one another. People are led to believe they are free because they can choose how to work or spend their money, but in reality, these choices are dictated by the structures of capitalism. The accumulation of wealth and power by the bourgeoisie enforces economic dependencies that limit true freedom for the majority. As the rich consolidate their control over property and production, the proletariat (working class) is left with no real autonomy, becoming increasingly dependent on wage labour to survive. Rousseau explains that this form of alienation extends beyond just material wealth; it also corrupts human relations and the social fabric. In capitalist societies, individuals become obsessed with competition, status, and wealth, striving to meet the demands of an economic system that commodifies human life. This leads to a situation where people no longer relate to one another as equals but are instead divided by social hierarchies. Rousseau laments that in this system, people are constantly driven by amour-propre (a form of pride or vanity that emerges from comparison with others), leading to unhappiness and social discord. Thus, while modern societies claim to value liberty, Rousseau argues that true freedom has been lost. Instead of living in harmony with their natural desires and instincts, individuals are trapped in a web of laws, customs, and economic dependencies that benefit the few and alienate the many. Rousseau believed that this situation was unnatural and detrimental to human well-being, leading him to propose a return to a more egalitarian form of social organization where individuals collectively govern themselves and prioritize the common good over personal gain. Rousseau’s vision of freedom, then, is not the illusory freedom offered by capitalism, which privileges the right to accumulate property and wealth at the expense of others. Rather, he advocates for collective freedom, where individuals participate directly in the formation of laws and share resources equitably, ensuring that no one is subjected to domination by others. Only in such a social contract, according to Rousseau, can true freedom be realized—freedom not just from external constraints, but from the alienation and inequality that arise from private property and capitalist exploitation

Facault’s panopticon and the critical awareness of power structures

Michel Foucault’s exploration of power dynamics reveals a profound critique of the illusion of freedom that pervades modern society. In his later works, particularly in “Discipline and Punish” and “The History of Sexuality,” Foucault posits that power is not merely repressive but is also productive, shaping identities and behaviours through complex social structures. He argues that individuals internalize societal norms and rules, leading to a form of self-surveillance where they regulate their own actions according to the expectations imposed upon them. This pervasive surveillance creates an illusion of freedom, as people believe they are making autonomous choices, when in fact, their options are heavily constrained by institutional practices and cultural narratives.

Foucault’s notion of the “panopticon” illustrates this idea vividly, representing a model of social control where individuals behave as if they are always being watched, thus conforming to norms to avoid punishment. This surveillance extends beyond formal institutions like prisons and schools to everyday interactions and language, which reinforce societal expectations and limit the scope of personal agency. Consequently, human existence becomes tragically defined by the internalized constraints that govern behaviour, resulting in a disconnection from genuine autonomy and the true expression of self.

To overcome this tragic existence, Foucault advocates for a critical awareness of the power structures that shape individual identities. He emphasizes the need for resistance and the importance of questioning accepted norms and values. By recognizing the mechanisms of power that operate subtly within society, individuals can begin to dismantle the illusions of freedom that bind them. Foucault suggests that through critical self-reflection and collective action, people can create spaces of resistance that challenge the status quo, fostering alternative identities and forms of existence that are more authentic and liberated. In doing so, individuals can reclaim their agency and transform the tragic nature of their existence into a more empowered and liberated state of being, cultivating new ways of relating to themselves and others that transcend the limitations imposed by societal structures.

Nietzsche and the Tragic Condition of Human Existence

Friedrich Nietzsche took the Greek conception of tragedy and refashioned it for the modern world. Nietzsche’s “The Birth of Tragedy” reveals his deep admiration for the ancient Greek worldview, particularly the Dionysian understanding of life, which embraces suffering and chaos rather than denying or fleeing from it. He argued that life, at its core, is a continuous cycle of creation and destruction, filled with suffering and irrational forces. The Apollonian side of Greek culture, symbolizing order and reason, attempts to impose meaning on this chaos, but it can only provide temporary solace. For Nietzsche, the tragic condition of human existence is not something to be feared or avoided but embraced. He famously declared, “Man is something that shall be overcome.” The tragedy of human life stems from our limitations, yet within this tragedy lies the possibility of greatness. Nietzsche’s concept of the Übermensch embodies this tension, as it represents a figure who transcends traditional morality and embraces the chaos and suffering of life to create new values. In Nietzsche’s view, life is tragic because it has no inherent meaning, but this very absence of meaning gives individuals the freedom to create their own purpose. In “Thus Spoke Zarathustra,” Nietzsche writes: “To live is to suffer; to survive is to find some meaning in the suffering.” This echoes his broader philosophy of existential struggle, in which individuals must confront the absurdity of life and make meaning through their will to power. Life’s tragic condition, for Nietzsche, is not something to be lamented but celebrated, as it forces humanity to rise above complacency and comfort.

Friedrich Nietzsche, in his exploration of the human condition and social life, famously remarked, “Give me a mask, and I will tell you the truth.” This quote emphasizes how individuals often conceal their true selves behind masks, adopting roles dictated by societal expectations, conventions, and pressures. For Nietzsche, life itself is a masquerade in which people wear these masks to hide their authentic desires, thoughts, and vulnerabilities. In this theatrical existence, truth and authenticity are veiled, and individuals engage in a performance shaped by external influences rather than their own inner essence.

Nietzsche’s idea of life as a masquerade resonates deeply with Martin Heidegger’s concept of “Eigentlichkeit” authenticity and “Uneigentlichkeit” inauthenticity in life. In his seminal work, “Being and Time”, Heidegger explains that most people live in a state of inauthenticity, conforming to societal norms and expectations—what he calls das Man or the “They” (the collective force of society). In this mode, individuals are absorbed in the superficial roles and identities imposed upon them, much like wearing a mask. They lose touch with their true potential and inner self, avoiding the confrontation with their own mortality and the fundamental nature of existence, which Heidegger refers to as Being-towards-death.

However, Heidegger also posits the possibility of living authentically, which involves recognizing one’s finite existence, confronting the anxiety that arises from the awareness of death, and making choices that reflect one’s true self, free from societal constraints. Nietzsche’s metaphor of the mask aligns with Heidegger’s notion that authenticity requires individuals to remove the social and psychological disguises they wear and face the world—and themselves—directly, without illusion. Both philosophers challenge the individual to break free from the inauthentic masquerade of life and embrace the raw, often painful, truth of existence.

This tension between mask and authenticity reflects the broader existential struggle to live meaningfully in a world where societal forces constantly push individuals towards conformity, hiding their deeper selves behind a mask of propriety and expectation.

Sartre and Existential Anguish

Building on Nietzsche’s ideas, Jean-Paul Sartre took the notion of life’s tragic condition into the realm of existentialism. In Sartre’s philosophy, the core tragedy of human existence lies in the concept of freedom, which he ironically views as the very source of our suffering. Sartre posited that humans are “condemned to be free”—there is no preordained essence or purpose to human life, and we are radically free to define ourselves through our choices. However, this freedom also brings with it an overwhelming sense of responsibility and anguish. In “Being and Nothingness”, Sartre explains how humans live in constant tension between their facticity (the unchangeable aspects of their existence, like birth, death, and social constraints) and their transcendence (the ability to project themselves toward the future and shape their lives). Yet, even this freedom is tragic because it forces us to confront the absurdity of existence—there is no inherent meaning, no guiding moral compass beyond what we create. Sartre’s famous statement, “Existence precedes essence,” underscores this idea: humans are not born with a predetermined purpose; they must define their own essence through their actions. Sartre’s conception of bad faith is also essential to understanding the tragic nature of human existence. Bad faith occurs when individuals deceive themselves into believing that their choices are determined by external forces—whether by religion, society, or fate—thus avoiding the anguish of freedom. However, this self-deception only deepens the tragedy of existence, as it leads to a life lived inauthentically, denying one’s freedom and responsibility.

The illusive freedom of consumerism

Modern societies’ illusion of freedom and choice permeates every aspect of consumerism, leading individuals to believe they are exercising autonomy over their lives. Advertisements and marketing strategies paint a picture of abundance, presenting a myriad of products and lifestyles as accessible options that cater to personal desires. However, this so-called freedom often masks the reality that choices are heavily influenced by corporate interests and societal norms. People are bombarded with curated selections that create an illusion of individuality while promoting conformity through brand loyalty and consumer trends. This paradox of choice can leave individuals feeling trapped in a cycle of consumption, where the pursuit of happiness through material possessions ultimately leads to disillusionment and emptiness, reinforcing the tragic nature of human existence in a world where true freedom is but a façade.

Read More:

https://capitalmarketjournal.com/on-capitalism-and-totalitarian-thought/: The thin horizon line at the boundaries of the Tragic Nature of Human Existence https://capitalmarketjournal.com/make-me-a-hinge-produce-in-the-most-efficient-way-in-the-shortest-time-with-essential-utilization-of-material/: The thin horizon line at the boundaries of the Tragic Nature of Human Existence https://capitalmarketjournal.com/on-being-and-existence-according-to-karl-jaspers/: The thin horizon line at the boundaries of the Tragic Nature of Human Existence