Love and Unity: Aristophanes’ Myth of Eros in Plato’s Symposium

Aristophanes manages to relieve himself of hiccups by applying a remedy – sneezing stimulation – suggested by Erissimachus, whose name, intentionally, means “fighter against belching.” The comic, teasing the doctor, notes that – curiously – the harmonious order (kosmion) of his body is restored only with noise and tickling.

Erissimachus jokingly tells him that if he starts laughing even before offering his speech, he will have to act as his guardian (phylax) to prevent him from becoming ridiculous even when he could speak in peace.

In his self-defense, Socrates asserts that Aristophanes, with his Clouds, has built an extraprocessual image that prejudices the process itself. The Republic theorizes the control of poetic activity by philosopher-rulers, called “guardians” (phylakes). Against this background, the exchange of banter between Erissimachus and Aristophanes appears allusive: one must be careful about what the comic poet Aristophanes says because his speech can impose clichés and evoke emotional reactions before reason can intervene to control them.

Aristophanes withdraws his joke and asks Erissimachus not to act as his guardian, because he fears being ridiculed. The doctor advises him to speak as if he had to justify everything he says, adding that he will certainly exonerate him, but only if he wants it. Rendering an account or logon didonai is, in the Republic, a fundamental element of Platonic dialectic. Here, it is approached by a verb typical of criminal procedure: representing the world in the manner of poets, without caring to account for what is said, can be deleterious not only philosophically but also politically, as anyone who remembers the influence of comedy on Socrates’ trial knows. Once again, reading the Platonic corpus as a network of associations adds value even to seemingly innocent exchanges of banter – but not so innocent as to induce Aristodemus to omit them and Apollodorus to omit them.

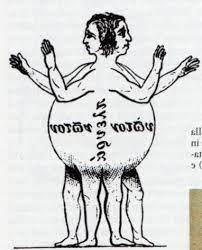

Aristophanes explains, jokingly imitating the style of doctors, that eros has a therapeutic value and is a source of the greatest eudaimonia for human beings. However, to understand it, one must understand human nature and its affections. Our original nature was different from the current one because it had three genders instead of two: male, female, and androgynous. The individual units – as seen in this image – were composed of what are now two men, two women, or, in the case of androgynes, a man and a woman, deriving, if male, from the sun, if female from the earth, and if androgynous from the moon. They were extraordinarily vigorous and proud, to the point of attacking the gods – just like the giants Ephialtes and Otus mentioned by Homer.

“What to do with them?” Zeus wondered. Slaughtering them, as he had done with the Giants, or striking them with lightning, would not have been a good solution, as the gods would have lost the honors and sacrifices they receive from men. The father of the gods, after mature reflection, devised a way to weaken them without suppressing them: by cutting them in two, turning them into bipeds, thus also achieving the advantageous effect of multiplying them. “And if then,” the god considered, “they continue to behave arrogantly, I will cut them again, forcing them to hop on one leg like in the sack race”.

Zeus began to cut, asking Apollo to turn the face of each half towards the cut and to sew their skin to form the navel, so that their punishment would always be before their eyes. However, the halves desperately sought to become whole again by trying to rejoin the other half, until they died. Zeus, to prevent the extinction of the species, moved the genitals to the front – previously they were outside because the original human beings reproduced directly with the earth, so that mating between men and women would produce children and that between males would provide relief and allow a return to normal occupations. This is why reciprocal eros is innate in human beings, because it reunites ancient nature by making two one and healing human nature as it is today. Each of us is only a symbolon of man, having been cut in two, and is in search of the symbolon that best suits him.

The descendants of the androgynous are heterosexual, those of the male or female whole are homosexual. Males who prefer males – says Aristophanes just like Pausanias – are not shameless as some claim, but are the best for audacity, courage (andreia), and virility, excelling in politics. If two halves meet again, they desire to be together with an intensity that cannot be explained solely by sexual union: the soul of each one wants something that it cannot say, but only obscurely presage. And if Hephaestus were to offer to reattach the two lovers, they would accept. This happens because our original nature was whole – and the epithymia of the whole is called eros. In this state of affairs, one must take care to behave orderly towards the gods, to avoid being cut again and having to face an even more difficult search for completion.