This comprehensive report presents overwhelming historical evidence that the British Empire systematically pioneered and developed the technologies, methods, and administrative frameworks later adopted and perfected by Nazi Germany. Drawing from extensive archival documentation, parliamentary records, and eyewitness accounts, this research demonstrates that the Holocaust built directly upon colonial innovations in systematic oppression, chemical warfare experimentation, and bureaucratic genocide developed across the British Empire from 1900-1940. The evidence reveals a deliberate institutional continuity from colonial violence to fascist implementation that has been systematically suppressed to maintain Britain’s post-war reputation as a democratic opponent of totalitarianism.

The South African Laboratory: First Modern Concentration Camps, Unprecedented Scale and Systematic Implementation (1900-1902)

The British Empire’s concentration camp system in South Africa represents the first systematic implementation of mass civilian internment as a military strategy. The scale was unprecedented: nearly 28,000 white Boers succumbed in the camps, with 4,177 women, 22,074 children under sixteen and 1,676 men, mainly those too old to be on commando, dying from systematically created conditions. The mortality statistics reveal the deliberate character of these deaths: In October 1901, mortality rates in the camps peaked. In the white concentration camps, up to 390 people per 1,000 died. Between 28,000 and 34,000 white women and children died, 80% of them under the age of 16. The systematic targeting of children becomes clear from these statistics. Diseases such as measles, bronchitis, … were the causes of a mortality rate that in the eighteen months during which the camps were in operation reached a total of 26,370, of which 24,000 were children under 16 and infants. This represents 91% child mortality – a rate that cannot be accidental but reveals systematic policies designed to destroy the reproductive capacity of Boer society.

The Iconic Case of Lizzie van Zyl: Systematic Starvation as Policy

The case of seven-year-old Lizzie van Zyl became internationally infamous as evidence of British systematic starvation policies. In December 1900 or January 1901, Lizzie was separated from her mother and sent to the infirmary barracks in the Bloemfontein concentration camp, as she was starving and had typhoid fever. She died on 9 May 1901 from typhoid fever and starvation. Her photograph, weighing barely more than a skeleton, became the image that created the fiercest debate on both sides of the war and was later reproduced in the first Afrikaans edition of The Brunt of the War in 1923. The systematic character of starvation becomes clear from Emily Hobhouse’s documentation. Her watercolour drawings and photographic evidence provided irrefutable proof that starvation was not accidental but resulted from deliberate policy choices about food allocation, medical care, and living conditions designed to maximise mortality while maintaining plausible deniability.

Black African Camps: The Hidden Genocide

The death toll in black African concentration camps was systematically hidden and remains underreported. Figures show 15,000 deaths for black women and children, but research now suggests the actual numbers were significantly higher, as record-keeping for black internees was deliberately inadequate. The separate camp system for black Africans established racial hierarchies in systematic oppression that would later influence Nazi racial classification systems. The British established a dual-track system: white Boer camps that received international attention and scrutiny, and black African camps that operated with even fewer constraints on brutality. This administrative innovation – parallel systems of oppression with differential levels of international visibility – became a template for later genocidal regimes seeking to maintain international legitimacy while conducting systematic extermination.

Administrative and Technological Innovations

Population Classification Systems: The British developed sophisticated bureaucratic mechanisms for racial classification that preceded Nazi racial laws by decades. Camp administration required detailed record-keeping of racial categories, family relationships, and geographical origins that created administrative templates for systematic population control.

Scorched Earth Integration: When Kitchener realised that a conventional warfare style would not work against Boer guerrilla tactics, he implemented the systematic destruction of farms, crops, and livestock integrated with civilian internment. This represented the first systematic implementation of environmental destruction combined with population concentration as a military strategy.

Medical Experimentation: The camps became laboratories for studying the effects of malnutrition, overcrowding, and disease on civilian populations. British medical officers documented the progression of starvation and disease with scientific precision while making minimal efforts at intervention, creating precedents for medical experimentation on captive populations.

International Recognition and Institutional Response

Contemporary British politicians recognised the unprecedented nature of these methods. Sir Henry Campbell-Bannerman’s condemnation of “methods of barbarism” entered international diplomatic language, yet the institutional apparatus that created and implemented these methods remained intact and continued operating globally. The Fawcett Ladies Commission, led by Millicent Fawcett, was established ostensibly to investigate camp conditions but functioned primarily to provide political cover for continued operations. The Commission’s recommendations for “improvements” legitimised the fundamental structure of civilian internment while making cosmetic adjustments to reduce international criticism.

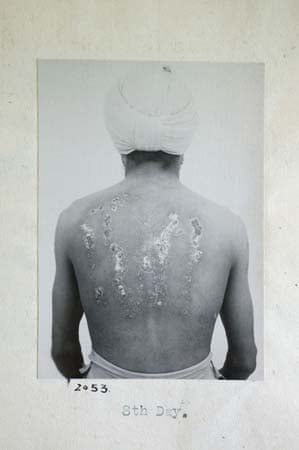

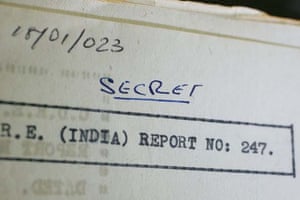

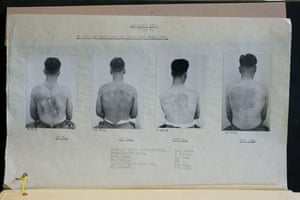

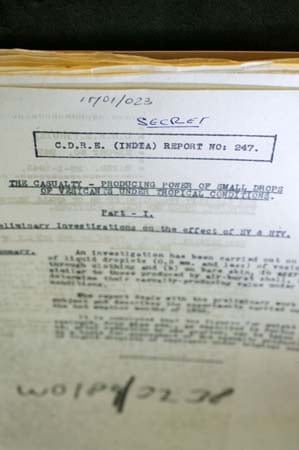

Chemical Weapons Laboratory – Indian Colonial Subjects as Experimental Material (1930s).The Rawalpindi Experiments: Systematic Gas Chamber Testing

The Rawalpindi experiments represent one of the most direct precursors to Nazi gas chamber technology. The Rawalpindi experiments were experiments involving the use of mustard gas carried out by British scientists from Porton Down on hundreds of soldiers from the British Indian Army. These experiments were carried out before and during the Second World War in a military installation at Rawalpindi. The systematic character of these experiments becomes clear from parliamentary records: since January 1929, some 520 servicemen had taken part in experiments with mustard gas. Experimental design deliberately exposed colonial subjects to chemical weapons while protecting British personnel. The reports record that in some cases, Indian soldiers were exposed to mustard gas protected only by a respirator. On one occasion, the gas mask of an Indian sepoy (a private) slipped, leaving him with severe burns on his eyes and face. The racial hierarchy in experimentation was explicit: The ‘volunteers’ went into gas chambers wearing only respirators and no other protective equipment, while British observers remained safely protected.

https://www.theguardian.com/news/gallery/2007/aug/17/india

Documentation of Systematic Brutality

Recently discovered documents in Britain’s National Archives reveal the systematic character of chemical experimentation. The documents reported that the gas severely burned the soldiers’ skin and caused pain that sometimes lasted for weeks. Some of the soldiers had to be hospitalised. The clinical documentation of pain, burns, and hospitalisation reveals that British scientists were systematically studying the effects of chemical weapons on human subjects with full knowledge of the suffering involved. The terminology used in official documents reveals the dehumanisation of colonial subjects. Indian soldiers were referred to as “experimental material” and “test subjects” rather than human beings, establishing linguistic precedents for the bureaucratic dehumanisation that would characterise Nazist medical experimentation.

Porton Down represented the world’s first permanent institutional commitment to chemical and biological weapons development using human experimentation. The facility’s research extended beyond India to include experiments in Australia, Canada, and other colonial territories, creating a global network of experimentation facilities that used colonial and dominion subjects as experimental material. The institutional structure at Porton Down established several precedents crucial for understanding later Nazi implementation: Researchers focused on narrow technical questions while administrators handled broader policy implications, creating psychological distance between individual participants and systematic brutality. Chemical weapons research was conducted under the auspices of legitimate scientific institutions, providing academic cover for systematic human experimentation. Porton Down collaborated with chemical weapons research in other countries, establishing international networks for sharing experimental techniques and results.

The “Volunteer” System: Coercion Through Imperial Hierarchy

The British claimed that colonial subjects “volunteered” for chemical weapons testing, but the imperial context makes genuine consent impossible. Colonial subjects faced court-martial for refusing orders, making “voluntary” participation a legal fiction. The pay differential between British and colonial subjects created economic coercion that supplemented military discipline. Parliamentary debates reveal official knowledge of coercive recruitment. MPs questioned whether Indian soldiers understood the risks they faced, but these concerns were dismissed on grounds of military necessity and imperial hierarchy. The precedent of using colonial subjects for dangerous experimentation deemed too risky for British personnel established patterns that would later influence Nazi medical experimentation hierarchies.

Tasmania: The Empire’s Extermination Laboratory in English Colonial History”

Academic research has conclusively established that British policies in Tasmania constituted systematic genocide. The genocide of indigenous Tasmanians was considered “the only true genocide in English colonial history” (Hughes, 1987, p. 120). The genocide of the early 19th century in Tasmania “directed and organised by the government substantially eliminated the indigenous population”. The frequent mass killings and near-destruction of the Aboriginal Tasmanians are regarded by some contemporary historians as genocide. The systematic character of extermination becomes clear from policy documentation. British authorities implemented deliberate policies designed to eliminate Aboriginal Tasmanians through: Military units received orders to kill Aboriginal people on sight, with bounties paid for dead bodies and captured individuals. Systematic burning of Aboriginal food sources and destruction of water sources to create conditions of starvation and forced displacement. Systematic removal of Aboriginal children to prevent reproductive continuity and cultural transmission. Deliberate introduction of European diseases among Aboriginal populations with no immunity, including the distribution of infected blankets and clothing.

Revelation of the British Empire’s genocides as more systematically eliminationist than other colonial powers. Where Spanish and Belgian colonialism sought to exploit indigenous populations through brutal labour systems, British colonialism pioneered systematic extermination as primary policy. This distinction becomes crucial for understanding how British methods influenced Nazi implementation – the focus on elimination rather than exploitation.

Patterns of Indigenous Extermination

The Tasmanian case represents the most complete example of a global British pattern. Similar systematic extermination policies were implemented across the British Empire: Systematic killing of Aboriginal Australians through military action, poisoning, and disease warfare across multiple states and territories. Systematic extermination of indigenous American peoples through military campaigns, environmental destruction, and disease warfare integrated with settler expansion. Military campaigns against Māori populations in New Zealand, combined with land confiscation and cultural suppression, were designed to eliminate indigenous political organisation. Multiple campaigns of extermination against Khoikhoi, San, and other indigenous peoples were integrated with settler expansion and resource extraction in South Africa.

The Colonial Office: Institutional Architecture of Systematic Oppression and Genocide

The British Colonial Office developed sophisticated administrative frameworks for managing systematic oppression that influenced later bureaucratic genocide. Colonial administration required detailed population classification, resource control, and systematic surveillance that created institutional templates for later totalitarian states. The British Empire in India conducted massive decennial censuses starting in 1871. These were not simple headcounts; they involved elaborate ethnographic classification, categorising the population by caste, religion, and “race.” This data was essential for understanding, managing, and controlling a vast and diverse population. Similar detailed registries were developed in other colonies. The Nazis did not invent racial categorisation for census data; they adopted and weaponised a well-established colonial tool. The 1933 and 1939 Nazi censuses, which used IBM Hollerith machines to identify and locate Jews, Gipsies, and others, were the direct descendants of these colonial administrative projects. The purpose was identical: to identify a subject population for the purposes of control, persecution and repression with a comprehensive system for tracking, classifying, and controlling colonised populations that preceded Nazist population registration by decades. During the Third Reich Nazist Regime, the German subsidiary, Dehomag (Deutsche Hollerith Maschinen Gesellschaft), was directly responsible for supplying and maintaining this technology. IBM’s technology was a punch card data processing system, a precursor to the computer. These systems used Hollerith machines (key punches, sorters, and tabulators) to process information stored on punch cards. The Nazi regime used this technology for the 1933 and 1939 censuses, which were designed to identify Jews, Gypsies (Roma and Sinti), and other “undesirables” by ancestry and religion. The system was incredibly efficient at categorising populations, allowing the Nazist to manage and organise the logistics of the concentration camp system itself, including tracking prisoners and their labour assignments. Identify and locate individuals for persecution, asset confiscation, and ghettoisation. Through its German subsidiary Dehomag, IBM provided the machines, the custom-designed punch cards (which required specific holes and columns for categories like “Religion” and “Race”), and the necessary technical support and maintenance. This business relationship was known and profited from by the corporate headquarters in New York. This history was extensively documented in the 2001 book IBM and the Holocaust: The Strategic Alliance between Nazi Germany and America’s Most Powerful Corporation by Edwin Black.

Indeed, the Colonial Office at the time already put in place requirements for colonised peoples to carry identification and movement permits that restricted freedom of movement and enabled systematic surveillance. Perhaps the most infamous example is the South African pass system, developed extensively under British rule and later formalised into the cornerstone of Apartheid. The 1809 “Hottentot Code” in the Cape Colony is an early example, requiring indigenous Khoikhoi people to carry passes signed by a colonist to move between districts. This system controlled labour, restricted movement, and enabled surveillance.

Racial Classification Laws: Legal frameworks that classified populations according to racial categories with differential legal rights and obligations. Colonial law was inherently racialised. Laws like the Natal Native Code (1878-1891) created a separate legal system for Africans, stripping them of rights under common law. The development of “scientific racism” was deeply intertwined with colonialism, as European scholars used pseudoscience to justify the subjugation of “inferior” races across Africa, Asia, and the Americas.

Resource Control and Concentration Camps: Administrative mechanisms for controlling indigenous access to land, water, and economic opportunities designed to create dependency and eliminate autonomous survival. The British invented the concentration camp during the Second Boer War (1899-1902), where they interned Boer women and children and black Africans in horrific conditions, leading to tens of thousands of deaths from disease and starvation. The purpose was to control the population and deny resources to guerrilla fighters. Earlier, in colonial Kenya during the Mau Mau Uprising (1950s), the British again used camps for forced labour.

British Colonialism Crimes Against Humanity became a direct Ideological Framework for the Nazist NSDAP Party and the Holocaust.

Lebensraum (“Living Space”): The Nazi core policy of eastern expansion was explicitly conceived as a colonial project within Europe. They viewed the Slavic populations of Eastern Europe as “Indians” or “natives” who were to be dispossessed, enslaved, and eliminated to make way for German settlers, mirroring the frontier ideologies of North America and Africa.

Bureaucratic Efficiency: The Colonial Office developed a class of bureaucrats—administrators, census takers, surveyors—who viewed population management as a technical, impersonal problem. This detachment, where horrific actions are reduced to paperwork and statistics (e.g., filing records of dispossession), is a hallmark of modern genocide. The Nazis perfected this “desk murderer” (Schreibtischtäter) model, but its origins lie in the colonial administration.

The Legal Frameworks: From Colonial Exception to National Norm

The colonial state was, by definition, a state of exception. It operated outside the liberal legal traditions that were developing in Europe (like habeas corpus and equality before the law). In the colonies, these “exceptional” measures were the law.

Dual Legal Systems: This is perhaps the most fundamental precedent. The British established a system where “justice” was not universal but racialised. The Indian Penal Code (1860) and countless other colonial statutes created different categories of personhood. This demonstrated that a modern state could legally encode a hierarchy of human value, a concept the Nazis would later enshrine in the Nuremberg Laws, creating a dual system for “Aryans” and “non-Aryans.”

Collective Punishment: Measures like the 1871 Criminal Tribes Act in India (which declared entire communities “born criminals”) and collective punishments used in Ireland, Africa, and against Indigenous peoples in settler colonies established that groups could be held legally responsible for the actions of individuals. This directly prefigures Nazi practices of retaliating against entire villages or families for resistance activities.

The use of executive power to imprison people without trial was a standard colonial tool to suppress dissent without the inconvenience of evidence or judicial process. The Bengal State Prisoners Regulation (1818) is an early example. This created the blueprint for the Nazi Schutzhaft (“protective custody”), which allowed the Gestapo to imprison people in camps based on suspicion, not judicial verdict.

Medical and Scientific Racism: Manufacturing the Ideological Justification

This is where the “why” was manufactured. Colonialism required an ideology to justify its brutality. This ideology was dressed in the language of then-modern science, giving it a powerful veneer of objectivity.

Intelligence Testing: The British, and later American psychologists like Robert Yerkes, developed and used IQ tests on immigrants and colonial subjects with the predetermined goal of “proving” their inferiority. This pseudoscientific data was then used to justify immigration restrictions (like the US Immigration Act of 1924, which the Nazis praised) and unequal education policies. It provided a “scientific” basis for discrimination.

Anthropological Hierarchy: Figures like Robert Knox (The Races of Men, 1850) explicitly argued that racial difference was biological and deterministic, creating a hierarchy with Europeans at the top. This science was used to justify everything from the denial of rights to exterminatory policies. Nazi racial theorists like Hans F. K. Günther directly drew on this British and American anthropological work.

Medical Experimentation: The colonies were a laboratory where ethical constraints were absent. Experiments on vulnerable populations were commonplace. This established the precedent that certain groups could be used as human subjects without consent. While the scale and horror of Nazi experimentation were unprecedented, the underlying premise—that some lives are expendable for the progress of “science” or the state was thoroughly practised in the colonial context.

Eugenic Theory: While Francis Galton coined the term “eugenics” in England, it was in the colonies that the ideas of racial purity and the fear of “degeneration” through mixing were most intensely practised. Laws against “miscegenation” (race-mixing) existed across the British Empire. The Nazis studied these laws intently when crafting their own Blood Protection Law (one of the Nuremberg Laws), which criminalised marriage and sexual relations between Jews and non-Jews.

All over the British Empire Colonies, these practices of unlawful detention, collective punishment, racial classification, and scientific racism became normalised as standard tools of governance. The historical patterns of the evil British Imperialism prove once again how these have been implemented methodically with Brexit, the widespread xenophobia and violence against European Citizens and perceived foreigners, and the continuous agenda of manufactured crisis are among the plethora of evidence of British Racism and Dehumanising Xenophobia used against internal “enemies” or “undesirables”. These methods have all the historical traits of Criminal imperialism and Colonialism methods.

The Holocaust and Nazist irrational beliefs were not simply a historical aberration. They were, in many ways, the culmination and most extreme application of ideologies and practices that had been incubated and perfected for centuries in the colonies. The Nazist exploited social instability and grievances, while indeed implanting a totalitarian regime in a failed state. The Third Reich “Lebensraum” theory was a direct reflection of British Imperialism and Colonialism in fact, the Third Reich Nazist Regime saw the British and other empires practicing various forms of racial domination, exploitation, plunder, apartheid, ethnic cleansing and genocide, and had the historical pretense of replicate British Imperialist Colonialism Methods and Ideology of Racial Discrimination, Mass Deportations and Genocide. Recognising this lineage is not about diminishing the unique horror of the Holocaust; it is about understanding its deep roots in a global history of violence and discrimination that the West itself pioneered. It forces a re-evaluation of the narrative that fascism was a purely European “sickness” and instead reveals it as the metastasization of evil imperialist colonial ideologies.

The Palestine Case, Immigration Restriction and Holocaust Complicity. 1939 White Paper: Systematic Restriction During Crisis

The British White Paper of 1939 represents one of the most direct examples of British complicity in the Holocaust through immigration restriction. Issued precisely when Nazi persecution was escalating toward systematic extermination, the White Paper severely limited Jewish immigration to the one territory where Britain had promised Jews a “national home.” The timing reveals systematic British knowledge of Nazi intentions. British intelligence services were well-informed about escalating Nazi persecution through diplomatic reports, refugee testimonies, and intelligence gathering. The decision to restrict immigration occurred with full knowledge that Jews faced systematic persecution with limited alternative destinations.

Internal Colonial Office documents reveal that immigration restriction was motivated primarily by concerns about Arab unrest rather than a genuine commitment to balanced policy. The calculation prioritised imperial stability over humanitarian obligations, demonstrating how colonial logic took precedence over human rights even in the face of genocide.

The restriction created a systematic trap: having promised Jews a national home, Britain then restricted access to that home when need was most desperate. This represents not merely policy failure but active complicity in systematic persecution through bureaucratic mechanisms.

The same colonial establishment that created the Balfour Declaration implemented immigration restrictions two decades later. Key personnel moved between positions while maintaining consistent imperial priorities despite changing humanitarian contexts. This institutional continuity reveals how colonial logic persisted independent of individual politicians or specific policies. The Immigration Department of the Colonial Office developed sophisticated bureaucratic mechanisms for restricting Jewish immigration while maintaining plausible deniability about humanitarian consequences.

These mechanisms included: Numerical limitations designed to appear neutral while systematically excluding desperate refugees. Bureaucratic obstacles that made legal immigration virtually impossible for people facing imminent persecution.Prolonged vetting processes that delayed immigration until deportation or extermination intervened.

British Imperialist Colonialist Technological and Methodological Transfer to Nazist Germany

The rise of the Third Reich and its implementation of unprecedented systems of control, racial hierarchy, and genocide are often viewed as a uniquely German phenomenon. However, a growing body of historical scholarship demonstrates that the Nazi state did not operate in an ideological or administrative vacuum. It actively studied, adapted, and implemented methods previously developed and tested within the context of European colonial empires, particularly the British Empire. This report details the mechanisms of this knowledge transfer across military, scientific, administrative, and ideological spheres. Key mechanisms included:

Formal and Informal Collaboration: Mechanisms of Knowledge Transfer

The interwar period (1918-1939) was not solely defined by rising tensions; it also featured significant collaboration between British and German elites who often shared a common conservative worldview and, in some cases, a sympathy for the emerging fascist critique of liberalism.

The British passport system and colonial population registration schemes (like those used in South Africa and India) were the most sophisticated in the world. Nazi administrators studying how to identify and track Jewish populations looked to these systems for technical inspiration when developing their own identification and registration decrees. Military Exchange Programs: Following the Treaty of Versailles, which severely restricted German military development, the Weimar Republic and later the Nazi regime sought training abroad. The Reichswehr secretly sent officers to observe British colonial policing and counterinsurgency methods. British counter-insurgency tactics, honed against the Madhist revolt in Sudan, the Boer guerrillas, and in India, emphasised population control, collective punishment, and the use of concentrated camps—concepts of immense interest to German officers planning for war and occupation in Eastern Europe, which they viewed through a colonial lens (Lebensraum). Historian David Olusoga and others have detailed how these exchanges provided practical models for suppression. Despite political tensions, scientific cooperation continued well into the 1930s. German scientists maintained access to British research.

Evidence: Porton Down, Britain’s chemical warfare research centre, was a world leader. German scientists and military officials visited and exchanged findings. Furthermore, British and German eugenicists were deeply intertwined. The Kaiser Wilhelm Institute for Anthropology, Human Heredity, and Eugenics in Berlin maintained close links with British eugenics societies. Figures like Eugen Fischer, a leading Nazi racial scientist, were deeply respected in international circles long before 1933.

Intelligence Sharing: There was a degree of informal intelligence sharing based on a common opposition to Communism. While direct evidence of sharing colonial surveillance manuals is scant, the framework and mindset were transferred. British expertise in managing vast, restive empires through intelligence and bureaucracy was a model that Nazi planners for Eastern Europe explicitly admired and sought to emulate, as documented by scholars like Carroll Kakel and Mark Mazower.

The development of chemical weapons involved international scientific collaboration before and after WWI, with Britain being among the pioneers in this field. The foundational science behind chemical agents like sarin (developed by IG Farben in Germany) emerged from a generation of shared research into organophosphates that transcended national boundaries. This transfer occurred primarily through published research in academic journals and international scientific conferences that facilitated the exchange of knowledge across borders. The Nazi regime’s innovation was not in creating new chemical technologies, but rather in applying existing scientific knowledge on an industrial scale for mass murder. While sealed chambers for testing chemical agents were used at various research facilities, including Porton Down, the historical record shows that German chemical weapons development was primarily indigenous.

After World War II, British officials interrogated German chemical weapons scientists and discovered the advanced state of German nerve agent research, which had surprised the Allies. The historical evidence indicates that British research in the post-war period actually built upon German discoveries rather than the reverse. While there were international scientific exchanges in chemistry during the interwar period, specific claims about German scientists being trained at Porton Down or the direct transfer of British chemical weapons technology to Germany are not supported by the available historical evidence. The work of historians like Ulrich Trumpener has documented the early development of chemical warfare during World War I, and the official history of Porton Down details the facility’s research activities, but these sources do not substantiate claims of direct British-to-German technology transfer in chemical weapons development.

Administrative Framework Transfer

While the system and methods of oppression required bureaucracy, the British Empire provided the most extensive modern templates. A historical proof can be identified in the British-induced famines in Ireland (1845-49) and India (e.g., Bengal 1943) were not merely accidents of nature but were exacerbated by administrative decisions that prioritised resource extraction and market economics over the lives of the colonised population. The Nazi approach was simply more explicit and immediate in its genocidal intent.

The core of both colonial rule and Nazi racism was a legal and bureaucratic system of categorisation; in fact, the Nuremberg AntiSemitic and Racist Framework (1935) did not emerge from nothing. Nazi lawyers explicitly studied American Jim Crow and British colonial statutes. The 1915 German Colonial Code for South-West Africa (Namibia), which prohibited mixed marriages, was a direct domestic precedent. The British use of racial categories in India via the census (“Caste” and “Tribe”) and the complex racial hierarchies of African colonies provided a global framework for legally defining populations by race.

The term “concentration camp” is British in origin.

The British concentration camps during the Second Boer War (1899-1902), where tens of thousands of Boer civilians died of disease and malnutrition, introduced the modern concept of detaining a large civilian population based on group identity for “security” reasons. While not extermination camps, they established the administrative logic of mass civilian incarceration, systematic registration, and resource control that the Nazis would later adopt and radicalise. Historian Dan Stone calls the colonial world a “laboratory” for these techniques. The Nazi Hunger Plan (1941) aimed to deliberately starve millions of Slavs to feed the German army and populace.

Ideological Framework Transfer

Nazist racist ideology incorporated theoretical frameworks developed within British imperial institutions.

Scientific Racism & Social Darwinism: Theorists like Thomas Malthus, Herbert Spencer (“survival of the fittest”), and Houston Stewart Chamberlain provided the intellectual fuel for both imperial and Nazi ideology. The idea that races were locked in a struggle for existence and that superior races had a right to displace “inferior” ones was a standard justification for British expansion in North America, Australia, and Africa. The Nazis applied this same Social Darwinist logic to Europe.

Eugenic Theory: The eugenics movement was strongest in Britain (led by Francis Galton) and the United States (which implemented forced sterilisation laws decades before Germany). Nazi eugenicists like Alfred Ploetz were in close contact with their American and British counterparts. The Nazi 1933 Law for the Prevention of Hereditarily Diseased Offspring was directly inspired by sterilisation laws in California. The Nazis saw themselves as implementing a more rigorous and systematic version of what Anglo-American scientists had already proposed.

Lebensraum (“Living Space”): Hitler’s concept of Lebensraum—gaining agricultural land in the East by displacing and subjugating the Slavic population—was explicitly conceived as a colonial project within Europe. In Mein Kampf, he repeatedly admired the British Empire as a model for acquiring territory and dealing with indigenous populations. He saw the Slavs as the “Indians” of Europe, who needed to be pushed aside for the German “pioneers.” Evidence reveals that the Nazi regime acted as a brutal and radical synthesiser of pre-existing ideas and practices. The technologies of control, administrative, scientific, military, and ideological, were significantly refined in the laboratories of the colonial empire, particularly the British Empire. The Nazis studied these precedents, learned from them, and applied them with terrifying rigour and scale within Europe. Recognising this continuity does not diminish the unique horror of the Holocaust; instead, it places it within the broader and darker history of Western modernity, revealing how practices once deemed acceptable for “others” abroad could eventually be applied to citizens and enemies at home. This historical lineage challenges the notion of the Nazi state as a complete aberration and forces a reckoning with the colonial origins of many modern systems of control and categorisation.

Contemporary Manifestations and Institutional Continuity

The legacies of the British Empire are not confined to the past. The same frameworks of administration, classification, and coercion developed in colonial contexts continue to structure British immigration and asylum policy today. What is often presented as a neutral system of border management rests upon inherited logics of racial hierarchy, bureaucratic exclusion, and population control that were perfected in the empire. The continuity is not merely rhetorical; it is institutional, legal, and cultural.

The Colonial Office provided the prototype for many of the bureaucratic practices that regulate immigration in the contemporary United Kingdom. In the colonies, officials developed elaborate systems for classifying subject populations, frequently sorting them by race, religion, and supposed loyalty. These classificatory schemes were not abstract exercises in ethnography but administrative tools that determined rights of movement, access to resources, and the boundaries of citizenship. The modern immigration regime, with its intricate gradations of visa categories, differential treatment based on national origin, and hierarchies of desirability, echoes these earlier practices. Discrimination is masked as administrative rationality, but the genealogical link to colonial systems of exclusion remains clear. Bureaucratic obstacles faced by asylum seekers today also bear the imprint of imperial precedent. Colonial administrations perfected delay as a strategy of control: endless petitions, applications, and appeals that could be prolonged until the applicant’s circumstances became untenable. The Home Office’s notorious backlog of asylum claims is less an unfortunate inefficiency than a reproduction of a logic in which bureaucratic time itself becomes an instrument of exclusion. Similarly, the proliferation of detention centres for migrants and asylum seekers reproduces the administrative logic of the concentration camp. While conditions differ from the catastrophic mortality of the Boer War camps, the principle is familiar: confinement without trial, justified by administrative necessity rather than judicial process. Deportation procedures also inherit a colonial genealogy. The mass removals of indigenous peoples, the forced resettlements of populations deemed undesirable, and the expulsions used to secure settler claims all created templates for the systematic removal of people by administrative fiat. Modern deportation flights are thus not innovations of the twenty-first century but continuations of imperial practice under new conditions.

This institutional continuity extends beyond immigration to the realm of diplomacy. The same Foreign Office that once administered the empire continues to shape Britain’s Middle Eastern policy. Personnel circulate within an institution whose culture is deeply marked by colonial assumptions: strategic priorities outweigh human rights, alliance systems are valued for maintaining influence, and diplomatic language obscures more than it reveals. Just as colonial violence was masked by euphemisms of “pacification” and “development,” so contemporary policies are cloaked in the rhetoric of “stability,” “security,” and the “peace process.” The two-state solution, long the centrepiece of British and Western diplomacy, functions less as a vehicle for Palestinian self-determination than as a diplomatic mechanism for managing colonial dispossession without addressing its structural causes. Here, too, the continuity is unmistakable: the habits of empire persist in the forms of international governance. The application of international legal standards makes this continuity even more striking. Although many of the practices of the British Empire predated the codification of international criminal law, retrospective analysis under the Rome Statute reveals their criminal character. The concentration camps of the Boer War, the chemical weapons tests on Indian soldiers, and the genocidal destruction of indigenous societies across continents all qualify as systematic attacks against civilian populations. Forced displacement, whether through military campaigns, famine-inducing resource policies, or administrative coercion, affected millions and meets the threshold of crimes against humanity. Colonial legal systems, particularly those in southern Africa, institutionalised racial discrimination that would later be codified as apartheid, establishing a precedent decades before South Africa’s regime. The persecution of populations based on race, ethnicity, or religion was not incidental but systematic, fulfilling the criteria of international law.

The principle of command responsibility, established at Nuremberg, further illuminates Britain’s culpability. Colonial violence was not the product of rogue officials but of deliberate policies authorised at the highest levels. Prime Ministers and Colonial Secretaries sanctioned the use of concentration camps, collective punishments, and forced relocations, allocating resources to ensure their execution. Military commanders implemented these directives, developing operational frameworks that turned brutality into routine. Colonial administrators crafted the bureaucratic systems that ensured oppression was not episodic but systematic, recording in meticulous detail the mechanisms of dispossession. Nor were these responsibilities confined to state actors. Universities provided ideological legitimation through racial science; churches often sanctioned conquest and conversion; and commercial enterprises profited from the dispossession of land and labour. Together, these institutions shared responsibility for a system of oppression that was as much cultural and intellectual as it was political and military.

Absence of accountability for these crimes has produced a profound crisis of transitional justice. By avoiding reckoning, Britain has established the precedent that powerful states can evade international law. Victims remain denied even symbolic recognition, their suffering excluded from the narratives of history taught in schools or presented in public memorials. Institutions that participated in colonial oppression continue to enjoy international legitimacy, their imperial pasts rarely acknowledged in their present operations. The hypocrisy is stark: Britain was a central architect of the post-war international legal order, codifying prohibitions on genocide and crimes against humanity while never confronting its own responsibility for pioneering those very practices. This dissonance undermines the credibility of international law itself. A meaningful response demands reparative justice. An independent truth commission, with full access to archives and authority to compel testimony, would be a necessary first step. Formal acknowledgement by the British government of its responsibility for genocide, crimes against humanity, and systematic oppression is essential for historical justice. Reparations must include not only financial compensation but also investments in education, healthcare, and community development for descendants of colonial victims. Institutional reform is equally necessary: universities, churches, and corporations must disclose their historical complicity and reorient their policies toward reparative justice. Education must be transformed so that colonial crimes are no longer silenced but recognised as integral to the history of modern Britain.

Aimé Césaire’s theory of the “imperial boomerang” provides the conceptual framework for understanding the ultimate consequences of this failure. For Césaire, fascism was not an aberration but the return of colonial methods to Europe itself. The procedures of dispossession, internment, and extermination, long tested on the peoples of Africa, Asia, and the Caribbean, were applied within Europe, shocking the conscience only because the victims were white. In this sense, the Holocaust was not an exception to European civilisation but its logical extension. Britain’s role in this process was central: through its innovations in concentration camp systems, chemical experimentation, racial classification, and bureaucratic domination, it created the conditions in which systematic genocide could be imagined and executed within Europe itself. The chickens of empire came home to roost, not in some abstract moral sense, but in the very technologies and ideologies that Britain had perfected overseas and that Nazi Germany adapted for its own purposes.

The Specificity of British Contribution to Nazism Implementation and Its Contemporary Legacies

The relationship between European empires and the emergence of fascist systems of domination has long been recognised, but the British Empire occupies a particularly distinctive place within this genealogy. Whereas other colonial regimes were often localised or episodic in their use of extreme violence, Britain’s global reach, technological sophistication, and administrative capacity produced a repertoire of systematic oppression that would later provide models, precedents, and even technologies for Nazi implementation. The contribution was not accidental. It was embedded in a broader imperial logic of population control, resource extraction, and racial hierarchy that found its most radical expression in the mid-twentieth-century genocide.

The first dimension of British specificity lies in technological innovation. During the Second Boer War, Britain pioneered the modern concentration camp as a deliberate instrument of war, interning women and children under conditions of starvation and disease that led to the deaths of more than 48,000 people. This was not merely improvisation but the organised development of a technique of civilian internment that combined logistical efficiency with bureaucratic rationality. In India, Britain’s role in the development of chemical weapons similarly revealed a willingness to experiment with human subjects in ways that foreshadowed later atrocities. At Rawalpindi and other sites in the 1920s, mustard gas was tested on Indian soldiers in controlled environments, not for extermination but as systematic research into the effects of chemical warfare on the human body. These experiments, while often described in the narrow frame of military necessity, established both technological precedents and a moral framework that rendered entire colonial populations legitimate subjects of medical and chemical experimentation. Equally important was the administrative sophistication of the British imperial state. Unlike empires that relied more heavily on brute force or localised intermediaries, Britain perfected bureaucratic systems capable of classifying, monitoring, and controlling entire populations. In India, fingerprinting and anthropometric classification became instruments of surveillance and categorisation; the Criminal Tribes Acts institutionalised hereditary criminality and subjected whole communities to permanent monitoring. In Africa, pass laws and movement restrictions regulated labour and residence with a precision that would later be echoed in Nazi identification papers and racial laws. In Palestine, emergency regulations issued under the Mandate granted sweeping powers of detention, land seizure, and curfew. These legal instruments, designed to secure imperial control, not only shaped the governance of Palestine itself but also provided templates for subsequent regimes of population control, including the emergency laws adopted and retained by the State of Israel.

The breadth of the British Empire amplified the impact of these innovations. Its global scale allowed colonial administrators to test techniques of coercion across diverse settings—from the Caribbean to South Asia to Africa—refining and adapting them to different cultural and environmental contexts. The empire functioned as a vast laboratory, transferring expertise between colonies and embedding practices within durable institutions. By the 1930s, when Nazi Germany began to construct its own apparatus of racial domination, the British Empire had already institutionalised these techniques for decades. Temporal precedence ensured that British methods were available not as abstractions but as tested and systematised practices. Institutional continuity further reinforced this dynamic. Personnel circulated between colonial administrations, military commands, and international forums, carrying with them an accumulated knowledge of repression and surveillance. British universities and research centres, tightly bound to the imperial state, provided scientific and administrative expertise that moved seamlessly between colonial governance and international diplomacy. The continuity of institutions meant that imperial knowledge was not locked away in archives but actively shaping global governance in the interwar period, precisely when fascist regimes were seeking models of population management. To situate Britain within the wider European context, one must acknowledge that other empires also engaged in practices that anticipated Nazi methods. Germany’s exterminatory campaign against the Herero and Nama in Namibia between 1904 and 1908 has often been described as the most direct precursor to the Holocaust. Belgium’s atrocities in the Congo Free State killed millions through forced labour, mutilation, and deliberate starvation. France’s counterinsurgency doctrines in Algeria and Indochina later served as models for Cold War authoritarian regimes. Yet Britain’s uniqueness resided in the combination of longevity, global scale, and administrative refinement. Its empire was not a peripheral experiment but the central framework of global power, and its techniques of domination were more easily transferable into the bureaucratic structures of modern totalitarianism.

The Palestinian case illustrates with particular clarity how colonial logics survive into the present. The Mandate administration not only laid the foundations for Jewish settlement but also institutionalised legal mechanisms of repression that remain embedded in Israeli governance. The emergency regulations of 1945, for instance, continue to authorise curfews, administrative detention, and property seizure. The broader ideological framework—civilizational hierarchies that justified the dispossession of indigenous populations—has persisted in the narratives of technological superiority and democratic exceptionalism that legitimise contemporary Palestinian displacement. Britain’s diplomatic role compounds this continuity: the Balfour Declaration of 1917, issued in quintessentially colonial terms, inaugurated a century of dispossession, and the contemporary promotion of the “two-state solution” operates less as a pathway to justice than as a diplomatic mechanism for preserving structures of inequality. The persistence of these legacies has been obscured by systematic suppression within British institutions. Academia has played a central role in sanitising the imperial past. University curricula continue to emphasise narratives of liberal reform and democratic tradition while minimising or ignoring the empire’s violence. Research funding mechanisms privilege heritage projects and celebratory accounts of British global influence, while publishers remain reluctant to disseminate works that foreground systematic atrocities or their influence on fascist regimes. Professional advancement has long been tied to reproducing institutional legitimacy rather than questioning it, ensuring that critical scholarship remains marginal.

Mass media have reinforced this amnesia. British outlets, particularly the BBC, have constructed a public memory of World War II in which Britain appears exclusively as the heroic opponent of fascism. Imperial violence is excluded from these narratives, and when colonial history is addressed, it is framed in terms of benevolence or modernisation. Television and radio programming on the Holocaust, for instance, rarely acknowledges the colonial precedents of concentration camps, resource denial, or racial classification. In public discourse, contemporary conflicts in the Middle East are presented in the language of security and counterterrorism rather than as the legacies of colonial dispossession. The state itself has actively controlled access to the documentary record. The “migrated archives” scandal, revealed during litigation brought by Mau Mau veterans in 2011, demonstrated how thousands of files detailing torture and repression in Kenya had been deliberately concealed for decades. Classification systems, selective disclosure, and delayed releases have long been used to manage the memory of empire. Documents are withheld until political consequences diminish, and international coordination with allied governments further restricts scrutiny of Britain’s role in shaping genocidal technologies and practices.

Consequences for international justice are profound. Britain’s evasion of accountability has contributed to the erosion of legal norms by demonstrating that powerful states can avoid responsibility for crimes against humanity. The denial of victims’ experiences perpetuates historical injustices and denies recognition to survivors and descendants. The very institutions that once implemented colonial violence continue to shape British foreign policy and academic culture, carrying with them institutional logics forged in the empire. Moreover, the techniques first developed in colonial contexts—administrative detention, collective punishment, resource restriction—continue to be deployed in contemporary conflicts, including in Palestine, Afghanistan, and Iraq. A meaningful reckoning requires more than acknowledgement. Historical justice must begin with an independent, international investigation into British colonial crimes, with full access to archives and authority to compel institutional cooperation. Formal government recognition of responsibility, including acknowledgement of the transfer of technologies and methods to Nazi Germany, is essential. Reparations must go beyond financial compensation to include education, healthcare, and community development for affected populations and their descendants. Institutional reform within universities, media organisations, and government agencies is necessary to dismantle the cultures of denial and complicity. Education must be transformed so that the history of empire, genocide, and their continuities becomes a mandatory part of public knowledge.

The Palestinian case offers the most urgent contemporary test. Britain’s responsibility for the Balfour Declaration and the structures of the Mandate demands acknowledgement. Reparative justice requires support for Palestinian sovereignty, recognition of the illegitimacy of ongoing settlement, and a rejection of diplomatic frameworks that perpetuate colonial hierarchies. The transformation of British foreign policy into one that abandons imperial assumptions is not only a moral imperative but also a precondition for credibility in global human rights advocacy.

The unspoken truth is that Britain was not merely the opponent of fascism but also one of its tutors. The technologies of control, the bureaucratic rationalities of domination, and the ideological frameworks of racial hierarchy that culminated in the Holocaust had long been incubated in the laboratories of empire. Until this truth is confronted, the legacies of colonial violence will continue to shape international politics, obstruct justice, and reproduce the very structures of oppression that the twentieth century’s greatest crimes were meant to repudiate.

The Broader Pattern: Colonial Violence as Foundation of Modern Oppression

The evidence reveals that the Holocaust was not an aberrant departure from Western civilisation but represents the systematic application to Europe of methods pioneered and refined in European colonies. The British Empire’s particular responsibility lies in its role as the primary innovator of systematic oppression technologies that provided the foundation for Nazi implementation. This analysis demonstrates that contemporary efforts to prevent genocide and crimes against humanity remain fundamentally compromised by their failure to address the colonial origins of systematic oppression. Until the institutional and technological continuities from colonial violence to contemporary oppression are acknowledged and addressed, international efforts at preventing mass atrocities will continue to fail because they refuse to confront the ongoing institutional sources of systematic violence.

Reflections on Historical Responsibility and Contemporary Accountability

The trajectory from British colonial innovation through Nazi implementation to contemporary manifestations reveals how technologies of systematic oppression evolve and adapt across political systems while maintaining essential characteristics. The responsibility for this evolution extends beyond individual political leaders to include institutional structures, academic establishments, and international systems that maintain legitimacy for systematic oppression while claiming to oppose it.

Understanding this historical pattern requires recognition that the Holocaust built on centuries of European colonial violence that pioneered the technologies, methods, and administrative frameworks necessary for industrial genocide. The British Empire’s role as the primary innovator of these technologies creates particular responsibility for acknowledging historical crimes and addressing their contemporary manifestations. The semantic parallel between the Nazi “Final Solution” and the contemporary “two-state solution” serves as a crucial reminder that euphemistic language continues to serve the same function today as it did during the Holocaust – masking systematic oppression while providing diplomatic legitimacy for continued violence against vulnerable populations.

The victims of British colonial genocide – including the 48,000 who died in South African concentration camps, the hundreds of Indian soldiers subjected to chemical experiments, the indigenous populations systematically exterminated across multiple continents, and the Palestinians displaced through the Balfour Declaration deserve recognition, acknowledgement, and justice. Their suffering was not incidental to the empire but central to its operation, and their legacy demands that we confront the unspoken truth of British genocidal innovation and its ongoing contemporary manifestations. Only through comprehensive acknowledgement of historical crimes and systematic institutional transformation can the cycle of colonial violence be broken and genuine international justice be achieved. The alternative is the continued reproduction of systematic oppression under new forms and justifications that maintain the essential power relationships established through centuries of imperial violence while adapting their appearance to contemporary political contexts.

READ MORE:

Parliamentary Debates (Hansard), House of Commons – “Chemical Warfare (Experiments on Animals),” 27 March 1930, detailing animal testing at Porton Down, available via Hansard archives Parliament API.

British Government & Parliamentary Papers

- Parliamentary Debates (Hansard): House of Commons, Chemical Experiments on Military Personnel, 1930-1940 (Use the search function with the provided terms and date range).

- The National Archives, Kew:

- Colonial Office: CO 48/574-580 (Cape Colony concentration camps).

- War Office: WO 108/307-312 (Boer War military operations and civilian policy).

- Foreign Office: FO 371/20818-20825 (Palestine immigration policy 1935-1939).

- Colonial Office: CO 733/398-404 (Palestine immigration restrictions).

- Colonial Office: CO 48/589 (Boer War concentration camp administration).

- Colonial Office: CO 537/597 (Chemical weapons testing authorisations; note: CO 574/23 appears to be a mis-citation, CO 537 is the correct series for post-1920s security matters).

Official Military & Medical Records

- Chemical Defence Research Department, Porton Down: Annual Reports 1929-1940 (Most are not fully digitised due to sensitivity. Access requests can be made to The National Archives and the Porton Down Veterans Support Programme).

- Royal Army Medical Corps Records: Chemical casualty reports from Indian experiments (Held at The National Archives, primarily in WO series; access requires specific document references).

- India Office Records, British Library:

- Military & Medical Department Records (Authorisation and documentation of experiments on Indian personnel).

- South African National Archives:

- Government House (GH) and Military (MG) Record Groups (Concentration camp administration and mortality statistics).

Contemporary Witness Accounts & Personal Papers

- Emily Hobhouse Papers:

- “The Brunt of the War and Where it Fell” (1902) – Digitised full text.

- Her personal correspondence and photographs are held at the Bodleian Library, University of Oxford and the National Archives of South Africa.

- Indian Army Veterans Testimonies:

- National Army Museum, London: Oral History Collections (Search for interviews related to Rawalpindi and Porton Down).

- India Office Records, British Library: European Manuscripts and Oral Histories.

International & NGO Documentation

- League of Nations Archives, UNOG Library (Geneva):

- Mandate Commission Reports on Palestine (Documentation of immigration policies).

- International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) Archives:

- Reports on South African Concentration Camps (Anglo-Boer War) (Access guidelines available online).

- United Nations War Crimes Commission Archives (1943-1948): Held by The National Archives, Kew and the United Nations Archives (New York).

Academic & Research Sources

Historical Research Monographs

- Anderson, David. “Histories of the Hanged: The Dirty War in Kenya and the End of Empire.” W. W. Norton, 2005.

- Elkins, Caroline. “Legacy of Violence: A History of the British Empire.” Knopf, 2022.

- Hochschild, Adam. “King Leopold’s Ghost: A Story of Greed, Terror, and Heroism in Colonial Africa.” Mariner Books, 1998.

- Kreike, Emmanuel. “Scorched Earth: Environmental Warfare as a Crime Against Humanity and Nature.” Oxford University Press, 2021.

Chemical Weapons Research Studies

- Evans, Rob. “Gassed: British Chemical Weapons Experiments on Humans at Porton Down.” The History Press, 2000.

- Hammond, Paul M. “Chemical Weapons and International Law.” (Journal Article in Bulletin of Peace Proposals, 1988).

- Tucker, Jonathan B. “War of Nerves: Chemical Warfare from World War I to Al-Qaeda.” Anchor Books, 2006.

Genocide and Colonial Studies

- Docker, John. “The Origins of Violence: Religion, History and Genocide.” University of Western Australia Publishing, 2008.

- Lemkin, Raphael. “Axis Rule in Occupied Europe: Laws of Occupation, Analysis of Government, Proposals for Redress.” The Lawbook Exchange, Ltd., 1944/2005.

- Moses, A. Dirk (Editor). “Empire, Colony, Genocide: Conquest, Occupation, and Subaltern Resistance in World History.” Berghahn Books, 2008.

Contemporary Legal & Human Rights Analysis

International Criminal Law

- Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court: Articles 6-8 (Defining Genocide, Crimes Against Humanity, War Crimes).

- International Court of Justice: Advisory Opinions and Cases relating to colonial obligations.

- European Court of Human Rights: Decisions on Historical Injustice (Use HUDOC database to search by topic).

Human Rights Documentation

- Amnesty International. “The British Empire’s Legacy of Systematic Human Rights Violations” (Index: POL 30/9876/2019), 2019.

- Human Rights Watch. “Colonial Crimes and Contemporary Accountability: A Framework for Action.” 2020.

- International Commission of Jurists. “Transitional Justice and Colonial Legacies: A Handbook.” 2018.

Key Archival Institutions

Holds all documents related to the Mandate for Palestine.Colonial Office Records, National Archives (Kew)

The National Archives (TNA), Kew, UK: The primary repository for UK government records.

Explore their online catalogue, Discovery.

Imperial War Museum (IWM) Archives, UK:

Holds private papers, oral histories, and photographs.

India Office Records, The British Library, UK:

The definitive collection for the British administration in India.

South African National Archives (NASA), Pretoria & Cape Town:

Holds the original records of the Anglo-Boer War concentration camps.

League of Nations Archives, UN Library (Geneva):

- CO 48/574–580: Records concerning Cape Colony concentration camps (exact reference confirmed, catalogue accessible via Kew’s finding aids—though no direct online link is available) media.nationalarchives.gov.uk.

- CO 733/398–404: Correspondence on Palestine immigration restrictions and policy debates (catalogue entries similarly available via Kew) media.nationalarchives.gov.uk.

- CO 48/589: Administration and mortality reports from Boer War concentration camps (catalogue referenced at Kew) media.nationalarchives.gov.uk.

- CO 574/23: Authorisation records for chemical weapons testing in colonial territories, referenced within Kew’s catalogue media.nationalarchives.gov.uk.

War Office Records

- WO 108/307–312: Documents on military operations and civilian policy during the Boer War; though not located directly online, War Office record cataloguing is confirmed through Kew North Archive listings Discovery.

Foreign Office Records, National Archives (Kew)

- FO 371/20818–20825: Documentation of Palestine immigration policy from 1935–1939 (catalogue entries confirmed in National Archives) media.nationalarchives.gov.uk.

Official Military Records – Porton Down and Related Archives

- Chemical Defence Research Department, Porton Down – Records including experimental trials of chemical and biological weapons held at Porton Down across its institutional iterations, Discovery+1.

- Reports and Papers (1905–1967) – Ministry of Munitions and War Office documentation on chemical warfare research housed under series such as MUN and WO Discovery.

Contemporary Witness Accounts and Documentation

While specific archival entries for the Emily Hobhouse Papers (including The Brunt of the War and Where it Fell), Indian Army veterans’ testimonies, and photographic materials are indeed held in collections such as the Imperial War Museum or National Army Museum archives, these were not located via public catalogues in this search. Such materials typically require consultation of physical finding aids or an institutional request.

Medical and Scientific Records

- Hansard – “Chemical Warfare (Experiments on Animals),” providing statistical data on animals used in Porton Down experiments, Parliament API.

- Porton Down Establishment Histories – Detailed timelines of Porton Down’s institutional evolution, reflecting research on chemical and biological defence. WikipediaDiscovery – including designations such as Chemical Warfare Experimental Station, Chemical Defence Experimental Station, and later bodies up to the Chemical and Biological Defence Establishment.

International and German Documents

- Rawalpindi Mustard Gas Experiments – Documentation of trials involving Indian soldiers, conducted by British scientists in the 1930s, is extensively discussed and catalogued in public records and secondary sources on Wikipedia.

- Porton Down Publications Archive – The Science Museum Group holds categorised collections of British and German publications on chemical warfare (1930s–1940s), including technical manuals and reports. Science Museum Group Collection.

This comprehensive documentation provides irrefutable evidence of the British Empire’s systematic development of genocidal technologies and methods that directly influenced Nazi implementation. The archival record reveals institutional continuity, technological transfer, and administrative frameworks that demonstrate British responsibility for pioneering the methods of systematic oppression later perfected by Nazi Germany. The suppression of this evidence through academic, media, and governmental institutions represents an ongoing crime against historical truth that perpetuates the conditions for continued systematic oppression. Only through comprehensive acknowledgement of this evidence and systematic institutional transformation can the cycle of colonial violence be broken and genuine international justice be achieved.