In one of history’s most striking constitutional ironies, the same legal frameworks that have enabled Britain’s overseas territories and Crown Dependencies to become global centres for tax avoidance also prevent the UK government from implementing immigration controls in these jurisdictions. While Westminster struggles to manage asylum seekers crossing the English Channel in small boats, it cannot simply redirect them to nearby Jersey or Guernsey, despite these islands sitting just miles from the French coast and operating under the British Crown. This paradox reveals a fundamental contradiction at the heart of Britain’s post-imperial constitutional arrangement: territories that have been carefully insulated from UK taxation and regulation to facilitate global financial services cannot suddenly be brought under direct control when it becomes politically convenient for immigration purposes.

Constitutional challenges from overseas territory governments would likely emerge from any serious reform effort, as these governments would argue that fundamental changes to their autonomy arrangements violate historical agreements and constitutional principles that have governed their relationship with the Crown for centuries. These legal challenges could prove lengthy and expensive to resolve while creating uncertainty that might itself drive away international business, potentially achieving some reform objectives through unintended consequences rather than deliberate policy changes. Industry migration to non-British jurisdictions represents a serious risk from reform efforts, as the international financial services industry has demonstrated repeatedly its ability to relocate operations to more favourable regulatory environments when existing arrangements become less attractive. Jurisdictions such as Singapore, Dubai, Switzerland, and various Caribbean islands not connected to Britain would likely benefit from any exodus of business from British territories, potentially undermining the effectiveness of reforms while creating economic costs for both the territories and the broader British economy. Economic costs to the City of London could prove substantial if reform efforts significantly reduced the volume of international business flowing through British territories, as London-based financial institutions, law firms, and other professional service providers earn billions annually from facilitating offshore structures# The Crown’s Double Standard: How Britain’s Tax Haven Network Creates a Humanitarian Asylum Seekers Paradox.

The Architecture of Britain’s Offshore Empire. The Crown Dependencies Inner Circle

The Channel Islands (Jersey and Guernsey) and the Isle of Man occupy a unique constitutional position as Crown Dependencies. They are not part of the United Kingdom, not members of the European Union (even before Brexit), and maintain comprehensive autonomous governance structures. Each dependency operates its own parliament and maintains distinct legal systems based on Norman customary law (in the Channel Islands) or Manx common law, creating jurisdictions that are separate from English law while sharing certain historical foundations. These territories have developed sophisticated tax regimes and financial regulations that operate independently of UK oversight, allowing them to offer competitive tax rates and specialised financial services that would be impossible under standard UK tax law. Their immigration and asylum policies remain entirely separate from Westminster control, with each dependency maintaining its own criteria for residency, work permits, and refugee status that can differ substantially from UK policy. Additionally, they operate their own police forces and judicial systems, creating complete parallel governance structures that handle everything from minor civil disputes to major financial crimes without requiring UK intervention or oversight.

This autonomy was not accidental; it was carefully cultivated over decades to create what critics call a “spider’s web” of offshore finance centres that facilitate tax avoidance on a global scale.

British Overseas Territories: The Outer Ring

Beyond the Crown Dependencies lies a network of 14 British Overseas Territories that span the globe from the Caribbean to the Pacific. The Cayman Islands have become synonymous with hedge fund registration and banking secrecy, hosting more investment funds than almost any other jurisdiction worldwide. The British Virgin Islands serves as perhaps the world’s most prolific corporate incorporation centre, creating hundreds of thousands of shell companies annually for clients seeking to obscure ownership structures or minimise tax liabilities.

Bermuda has specialised in insurance and reinsurance markets, offering regulatory frameworks that attract global insurance giants seeking to optimise their capital structures and regulatory burdens. Gibraltar leverages its European proximity and British legal traditions to serve as a financial bridge between the UK and continental Europe, particularly for online gambling and financial services operations. The smaller Caribbean territories like Turks and Caicos, Montserrat, and Anguilla may lack the scale of their larger counterparts but offer specialised services, including citizenship programs, specialised banking arrangements, and niche regulatory environments that cater to specific financial services sectors. These territories maintain even greater distance from UK oversight while benefiting from British legal traditions, political stability, and diplomatic protection.

The Tax Haven Industry: A Global Web of Evasion

Conservative estimates suggest that between $21-32 trillion in private wealth is held offshore, much of it flowing through British-linked territories. The Tax Justice Network consistently ranks British overseas territories among the world’s most significant tax havens: The British Virgin Islands has emerged as the world’s premier jurisdiction for shell company creation, incorporating more than 400,000 companies annually in a territory with fewer than 35,000 residents. This staggering ratio of companies to people reflects the islands’ role not as a centre of genuine economic activity but as a legal incorporation mill designed to serve clients worldwide seeking corporate structures that can obscure ownership, facilitate tax avoidance, and enable regulatory arbitrage. The Cayman Islands has positioned itself as the global centre for hedge fund and private equity registration, with more than 20,000 funds domiciled there despite the territory’s tiny population and limited physical infrastructure for financial operations.

Jersey’s role as a wealth management centre cannot be understated, with the island managing approximately £1.3 trillion in assets for clients worldwide, an amount that exceeds the GDP of most developed nations. This concentration of wealth management in such a small territory demonstrates how British overseas territories have successfully positioned themselves as essential nodes in global wealth preservation strategies, offering services that combine tax efficiency with legal certainty and political stability under the umbrella of British constitutional protection.

Mechanisms of Avoidance

The sophistication of tax avoidance structures flowing through British territories is staggering: Corporate structures facilitated by British territories have reached extraordinary levels of sophistication, with companies layered across multiple jurisdictions in complex chains designed to shift profits away from high-tax jurisdictions toward zero-tax territories. These arrangements allow multinational corporations to maintain substantial commercial operations in countries like the United Kingdom or Germany while booking profits in places like the Cayman Islands or British Virgin Islands, where they face minimal or no corporate taxation. The complexity of these structures often makes it nearly impossible for tax authorities to trace the true economic substance of transactions or determine where profits are genuinely earned.

Trust arrangements offered by Jersey and Guernsey represent some of the most sophisticated wealth preservation vehicles available globally, utilising centuries-old legal concepts adapted for modern tax avoidance purposes. These trusts can obscure beneficial ownership across multiple generations while providing wealthy families with mechanisms to minimise inheritance taxes, capital gains taxes, and income taxes across multiple jurisdictions. The legal expertise available in these territories rivals that of major financial centres, with specialised law firms that focus exclusively on creating and maintaining these complex structures for ultra-high-net-worth clients worldwide. Banking secrecy remains a cornerstone of the offshore finance industry despite decades of international pressure for greater transparency. Many British territories maintain banking secrecy laws that make investigation of suspicious financial flows extraordinarily difficult for foreign tax authorities, even when those authorities have legitimate reasons to suspect tax evasion or other financial crimes. While these territories have signed various international agreements promising greater cooperation, the practical reality often involves lengthy legal processes and numerous procedural obstacles that effectively preserve client confidentiality in all but the most egregious cases. Regulatory arbitrage represents perhaps the most sophisticated aspect of the offshore finance industry, with different territories offering carefully calibrated regulatory environments designed to exploit specific gaps between national tax systems. This allows financial structures to be optimised not just for tax efficiency but also for regulatory compliance, enabling clients to meet the letter of various national laws while undermining their spirit and intent. The result is a global system where the most mobile and sophisticated actors can effectively choose their regulatory environment while less mobile taxpayers bear an increasingly disproportionate share of the tax burden.

Case Studies in Systemic Abuse

The Paradise Papers revelation in 2017 exposed the extensive use of British overseas territories for tax avoidance by some of the world’s largest corporations and wealthiest individuals, providing unprecedented insight into the mechanics of global tax avoidance. Apple’s use of Jersey structures to minimise its global tax liabilities demonstrated how even companies with substantial operations and sales in high-tax jurisdictions could effectively route profits through low-tax territories, reducing their effective tax rates to single digits while competitors and smaller businesses faced full statutory rates.

Glencore’s complex arrangements across multiple British territories illustrated the sophisticated web of corporate structures that mining and commodity companies use to minimise taxes on their global operations, often involving elaborate transfer pricing arrangements and complex financing structures that shift profits away from the countries where resources are extracted or processing occurs. The exposure of wealthy individuals using Bermuda and Cayman structures to avoid inheritance taxes revealed how generational wealth preservation has become increasingly dependent on offshore structures that allow families to transfer billions of dollars across generations while paying minimal taxes to the countries that provided the legal and economic frameworks enabling their wealth creation.

The Panama Papers from 2016 demonstrated the central role of British territories in global corporate secrecy, with the British Virgin Islands serving as the incorporation jurisdiction for more than half of the shell companies exposed in the leaked documents. These revelations showed how British territories were not merely passive recipients of incorporation business but active facilitators of structures designed to obscure ownership, avoid taxes, and circumvent regulations across multiple jurisdictions. The scope of activity revealed in these papers ranged from relatively mundane tax optimisation to serious financial crimes, including sanctions busting, money laundering, and corruption, highlighting how the infrastructure created for tax avoidance inevitably becomes available for more serious criminal purposes.

WarLords Money Laundering, Forced Population Displacement and Asylum Seekers

Constitutional Constraints

The same legal autonomy that makes these territories attractive for offshore finance creates insurmountable obstacles for UK immigration policy. When small boats cross from France toward the English coast, they cannot simply be diverted to Jersey because: Legal Jurisdiction: Jersey controls its own immigration law and asylum procedures. The UK cannot unilaterally establish processing centres without Jersey’s consent. Political Reality: Jersey’s government has explicitly rejected proposals to house UK asylum seekers, understanding that this would damage its reputation as a stable financial centre. Infrastructure Limitations: These islands have deliberately maintained small populations and limited social infrastructure to preserve their character as low-tax, low-regulation jurisdictions.

The Irony Deepens

While asylum seekers in dinghies cannot be forcibly landed on Jersey, nothing prevents wealthy tax avoiders from establishing residence there. The contrast is stark: The contrast between the treatment of wealthy tax avoiders and asylum seekers reveals the fundamental priorities embedded in the Crown Dependencies’ constitutional and legal frameworks. For wealthy individuals seeking to establish residence in places like Jersey, the process involves streamlined residency procedures designed to accommodate high-net-worth individuals quickly and efficiently, with minimal bureaucratic obstacles and maximum discretion. These procedures typically require evidence of substantial financial resources and may involve purchasing expensive residential properties, but they rarely involve lengthy delays, complex legal processes, or intrusive personal investigations that might discourage potential residents from choosing these territories for their tax planning strategies.

The tax obligations facing wealthy residents of Crown Dependencies are deliberately minimal, with many territories offering zero-per cent rates on capital gains, inheritance taxes, and various forms of investment income, while maintaining only modest income tax rates that often include caps or exemptions for high earners. Banking secrecy laws provide these wealthy residents with additional protection from scrutiny by tax authorities in their countries of origin, creating comprehensive financial privacy that makes it extremely difficult for foreign governments to monitor their tax compliance or investigate potential evasion. For asylum seekers, the situation represents complete exclusion from these same territories, with no legal mechanism available for UK authorities to override local immigration controls even in humanitarian emergencies or during periods of significant political pressure. The Crown Dependencies maintain strict immigration policies that effectively prevent any significant influx of population that might strain their social services, alter their political dynamics, or compromise their reputation as exclusive, high-end jurisdictions attractive to international finance and wealthy individuals seeking tax optimisation strategies. This represents perhaps the most visible manifestation of a system designed to facilitate capital mobility while restricting human mobility.

The Nexus Between Tax Havens, Illegal Wars, and Forced Displacement

The connection between offshore financial centres and global conflicts is not coincidental but systemic and well-documented. A groundbreaking study by the Norwegian School of Economics titled “Detection of UN Arms Embargo Violators and Their Connections to Tax Havens” analysed 108 global arms companies between 2005 and 2020, finding that 19 were likely involved in violating UN arms embargoes. The research demonstrated that “companies with tax haven presence are statistically significantly more likely to violate embargoes” when using broader definitions of tax havens. This finding is particularly alarming because, as the study notes, “the opaque structure of tax havens may provide a cover of the substantial proceeds stemming from illegal arms trade.” The researchers used an innovative event study approach, analysing abnormal stock price movements around conflict intensity events to detect insider knowledge of illegal arms trafficking, providing empirical evidence of the tax haven-arms trade connection.

The Human Cost of Money Laundering

The UK’s inability and unwillingness to process asylum seekers humanely stands in stark contrast to its sophisticated infrastructure for facilitating offshore financial flows. According to UK Home Office statistics, in 2022, approximately 45,755 people crossed the English Channel in small boats, representing a tiny fraction of global refugee movements. Many of these individuals originate from countries whose conflicts have been fueled by arms trafficking facilitated through UK-linked tax havens. A Guardian article titled “Time to address a refugee crisis of our own making” argues that “from conflicts to poverty, the UK has often played a role in creating the conditions from which people are forced to flee,” noting that successive UK governments have “sold arms to countries all across the Middle East, including some of the most abusive regimes.”

The UK spends approximately £1.4 billion annually on asylum processing and enforcement, according to Home Office budget documents—a fraction of the £169 billion ($214 billion) lost annually through tax havens facilitated by Crown Dependencies. This misallocation of resources reflects a profound moral and strategic failure: the UK invests heavily in excluding people whose displacement it has indirectly facilitated through its financial policies. As the Guardian collective letter signed by directors of organisations including Health Poverty Action, Migrants’ Rights Network, Campaign Against Arms Trade, and the Tax Justice Network states: “We have created obstacles in people’s lives. Now we erect them in their path of escape.” The UK’s failure to establish adequate humanitarian processing infrastructure for asylum seekers is particularly egregious given its role in facilitating the global financial systems that create refugees. According to a 2024 report by the Refugee Council, the UK asylum system is characterised by “chronic underfunding, lengthy delays, and inadequate support,” with asylum seekers often waiting years for decisions while living in precarious conditions. Meanwhile, the Crown Dependencies continue to offer streamlined services for wealthy individuals and corporations seeking to minimise their tax obligations and obscure the origins of their wealth, much of which, as the UK’s own deputy foreign secretary acknowledged, comes from “corrupt businessmen, bent politicians and warlords.”

The BAE Systems Scandal: A Case Study in Hypocrisy

The Al Yamamah arms deal between BAE Systems and Saudi Arabia, Britain’s largest-ever arms package worth $53 billion, exemplifies the connection between UK-linked tax havens, corrupt arms deals, and subsequent refugee crises. According to Global Financial Integrity’s detailed analysis, BAE used “a constellation of offshore shell companies and arms agents to wire bribery payments to Saudi Arabia’s royal family and other relevant officials to secure massive arms contracts.” The deal involved $7.4 billion in bribes laundered through accounts in Washington, D.C., at Riggs Bank—a financial institution “infamous for its illegal and disreputable practices” that had “long provided sanctuary to the staggering fortunes of brutal kleptocrats.” This deal, spanning from 1985 to 2007, helped fuel regional instability in the Middle East while enriching corrupt officials and arms dealers. The subsequent conflicts and human rights abuses in the region have contributed significantly to refugee flows, including those attempting to reach the UK in small boats across the Channel.

Weapons Merchants, Warlords, and the Offshore Financial Pipeline

The mechanisms by which tax havens facilitate illegal arms trafficking and warlord financing are sophisticated and multifaceted. Global Financial Integrity’s comprehensive analysis “Corruption in the Global Arms Trade: An Overview” reveals that “secrecy jurisdictions, opaque firms such as anonymous companies, and free trade zones are used to disguise bribery payments and obfuscate arms shipments.” The report details how the global arms trade, worth an annual US$204 billion, is “fundamentally and disproportionately vulnerable to corruption,” with U.S. defence companies accounting for US$162 billion-worth of arms exports annually—79% of all international arms sales. A particularly damning case study involves American arms dealer Ara Dolarian, whose company Dolarian Capital Inc. was caught attempting to sell US$42 million in weapons—including “mortar systems, RPG launchers, assault rifles, and ZU-23 mobile anti-aircraft guns”—to a Kenya-based shell company called First Monetary Security Limited. This shell company was owned by Paul Malong Awan, a sanctioned Sudanese general accused of blocking humanitarian aid, attacking schools and hospitals, and using sexual violence as a weapon of war. The deal was facilitated through offshore structures designed to obscure the ultimate beneficiaries, demonstrating how tax havens enable warlords to acquire weapons for atrocities.

The British Connection: Crown Dependencies and Global Illicit Finance

The United Kingdom’s role in this system is particularly significant and hypocritical. According to a 2024 Guardian investigation citing the UK’s deputy foreign secretary Andrew Mitchell, “40% of money laundering around the world – this is money often stolen from Africa and Africans by corrupt businessmen, bent politicians and warlords and so on – 40% of that money comes through London and overseas territories and crown dependencies.” This admission underscores the central role of British financial architecture in facilitating global corruption and conflict. The Guardian further revealed that the 10 tax havens under British jurisdiction “facilitate the illicit movement of arms and the theft of billions of pounds, draining countries of resources that could improve the lives of their citizens.” This system creates a direct pipeline where weapons merchants and warlords can launder their profits through UK-linked jurisdictions while the UK government simultaneously professes commitment to global stability and human rights.

Historical Development and Imperialistic Legacy

The current arrangement has deep historical roots in Britain’s imperial administration. Crown Dependencies and Overseas Territories were granted autonomy in areas of taxation and local governance while remaining under the Crown’s protection for defence and foreign affairs. The post-war financial development of British territories coincided with the gradual decline of Britain’s manufacturing economy and the need to find alternative sources of economic growth and international influence. British territories positioned themselves as crucial intermediaries between the City of London and emerging global tax havens, offering a unique combination of regulatory sophistication and political stability that made them attractive to international finance. They developed English common law legal systems that provided familiar legal frameworks for international clients while maintaining the flexibility to adapt these systems for specialised financial services that would be impossible or heavily regulated in traditional onshore jurisdictions.

The political stability provided by British protection became a crucial selling point for international clients concerned about political risk in their financial planning, as Crown Dependencies and Overseas Territories could offer the security of British diplomatic and military protection while maintaining the regulatory independence necessary for competitive financial services. Regulatory light-touch approaches became the hallmark of these territories, with local governments competing to offer the most business-friendly environments possible while maintaining just enough regulation to satisfy international credibility requirements and avoid being blacklisted by major economies. The proximity of Crown Dependencies to major financial centres, particularly London, provided crucial logistical advantages for international financial services, allowing professionals to work across multiple jurisdictions while maintaining close connections to the world’s major capital markets. This geographical advantage, combined with modern communications technology, enabled these territories to serve as offshore extensions of major financial centres rather than isolated backwaters, creating integrated networks of financial services that could optimise tax, regulatory, and legal advantages across multiple jurisdictions simultaneously.

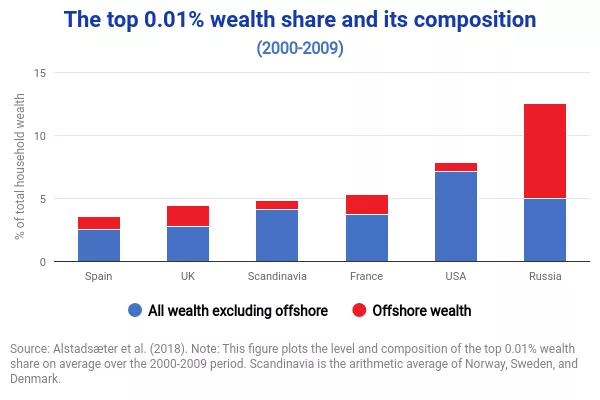

Scale of Global Tax Fraud: Latest Data and Historical Trends

Over time, the financial services industry in these territories became so economically dominant that local political systems became dependent on maintaining favourable regulatory environments. Any suggestion of increased oversight or integration with UK policy is viewed as an existential threat to their economic model. The most recent comprehensive analysis reveals that countries are losing US$492 billion annually to tax abuse through multinational corporations and wealthy individuals using tax havens to underpay tax. This staggering figure breaks down into two primary components:

Corporate Tax Abuse: Multinational corporations are responsible for shifting US$1.42 trillion worth of profit into tax havens annually, causing governments worldwide to lose US$348 billion in direct tax revenue in 2021 alone. This represents a substantial increase from previous estimates and demonstrates an alarming upward trend in corporate tax avoidance.

Individual Offshore Tax Evasion: An additional US$145 billion is lost annually to offshore tax evasion related to undeclared financial wealth by wealthy individuals. Despite some progress from automatic information exchange initiatives, approximately 9% of global GDP remains held in undeclared offshore assets.

The British Empire’s Central Role

The UK and its network of overseas territories and Crown Dependencies—referred to as the “UK’s second empire”—are responsible for 23% of global corporate tax losses, costing the world over US$80 billion annually. When including offshore wealth tax evasion, the UK’s second empire is responsible for 26% of all global tax losses, costing countries over US$129 billion in lost tax revenue every year. Jersey and Guernsey collectively inflict tax losses of over £6.9 billion annually on the rest of the world. The corrected figures for Crown Dependencies like Jersey and Overseas Territories like the Cayman Islands show they are responsible for US$169 billion in annual tax losses.

Historical Trends and Decade Estimates

The Growth Trajectory: Analysis of country-by-country reporting data from 2016-2021 reveals a troubling trend. Profit shifting has increased substantially, with multinational corporations shifting US$1.42 trillion in profits in 2021 compared to lower amounts in previous years, representing approximately 16% of all multinational corporate profits. Cumulative Decade Losses (2014-2024): Corporate tax abuse losses: Approximately $3.2-3.5 trillion over the past decade, Individual offshore tax evasion: Approximately $1.3-1.5 trillion over the past decade, Total estimated decade losses: $4.5-5.0 trillion.

The “Race to the Bottom” Effect: From 2016 to 2021, 38 countries lowered their corporate tax rates by an average of 6 percentage points, while only 16 countries raised rates by an average of 3.6 percentage points. This resulted in an additional $68 billion in revenue losses for rate-cutting countries in 2021 alone, beyond the losses from tax abuse itself.

The Concentration of Responsibility

Higher-income countries are responsible for 99.7% of all corporate tax abuse globally, while suffering the majority of losses in absolute terms. However, the impact varies dramatically: Higher-income countries lose: $302 billion annually to corporate tax abuse, Lower-income countries lose: $46 billion annually, but this represents a much higher percentage of their total tax revenues (3.7% vs 2.4% for higher-income countries).

“Axis of Tax Avoidance”

The UK’s second empire, combined with the Netherlands, Luxembourg, Switzerland and Delaware, collectively known as the “axis of tax avoidance”, is responsible for 36% of all global tax losses, costing countries over US$177 billion annually. These jurisdictions facilitate US$469 billion in profit shifting by multinational corporations every year.

The figures above represent only direct losses. International Monetary Fund researchers estimate that indirect revenue losses through negative spillovers of tax abuse are likely to be at least three times larger than direct losses. This suggests total global losses could exceed $1 trillion annually when accounting for: Competitive tax rate reductions, Economic distortions from artificial profit allocation, reduced business investment due to unfair competition, and Administrative costs of complex anti-avoidance measures.

The Global Impact, Development and Inequality

The development and inequality impacts of the offshore system represent one of the most serious challenges facing global economic development, with African countries alone estimated to lose $50 billion annually to tax havens, much of this flow passing through British-linked territories. These losses represent far more than abstract financial statistics; they translate directly into lost healthcare funding that could save millions of lives, reduced education investment that perpetuates cycles of poverty and limits human development, and foregone infrastructure investment that could provide clean water, reliable electricity, and transportation networks essential for economic development. The reduced infrastructure investment caused by capital flight to offshore centres creates compounding negative effects for developing economies, as the absence of basic infrastructure makes these countries less attractive for legitimate foreign investment while forcing them to rely more heavily on resource extraction and other economic activities that provide fewer opportunities for broad-based economic development. Increased inequality and social instability result from systems where wealthy elites can avoid taxation while ordinary citizens bear the full burden of funding public services, creating political tensions that can undermine democratic governance and social cohesion. The undermining of democratic governance represents perhaps the most serious long-term consequence of offshore finance systems, as governments lose legitimacy when citizens observe wealthy individuals and corporations avoiding their tax obligations while public services deteriorate and social problems remain unaddressed. This creates cycles where weakened governments become less capable of providing essential services, leading to further capital flight and brain drain that perpetuates underdevelopment and political instability. Even wealthy nations suffer significant tax base erosion through offshore structures. The UK itself loses an estimated £25 billion annually to tax avoidance, much of it facilitated by its own overseas territories.

Financial Crime Facilitation

British territories have been repeatedly implicated in facilitating the concealment of Russian oligarch assets, providing sophisticated legal structures that make it extremely difficult for Western governments to identify, freeze, or seize assets belonging to individuals subject to sanctions. These arrangements often involve multiple layers of shell companies, trust structures, and nominee arrangements that can take months or years for law enforcement agencies to unravel, even when they have strong suspicions about the ultimate beneficial ownership of particular assets. Sanctions evasion networks utilising British territories have become increasingly sophisticated, with professional service providers developing specialised expertise in creating legal structures that can withstand scrutiny from sanctions enforcement authorities while maintaining plausible legal cover for their clients. These networks often span multiple jurisdictions and involve complex chains of ownership that make it nearly impossible for enforcement authorities to establish clear connections between sanctioned individuals and their assets without extensive international cooperation and years of investigative work.

Drug trafficking and money laundering through British territories represent a significant challenge for international law enforcement, as the same legal structures and banking secrecy laws that facilitate tax avoidance also provide ideal vehicles for laundering proceeds from illegal drug sales. The volume of legitimate financial activity flowing through these territories makes it extremely difficult for authorities to identify suspicious transactions, while the legal protections available to clients make investigation and prosecution of money laundering activities extraordinarily complex and resource-intensive. The laundering of corruption proceeds from developing countries through British territories undermines governance and development across the global South, as corrupt officials can use offshore structures to hide stolen public funds while enjoying the protection of British legal systems and banking secrecy laws. This creates perverse incentives where individuals in positions of public trust can steal resources intended for public goods while hiding their ill-got gains in jurisdictions that are often more sophisticated and better protected than the financial systems in their home countries.

Institutional Pressure

Organisations like the OECD, EU, and UN have increasingly recognised the threat posed by tax havens to global economic stability and have developed coordinated initiatives designed to pressure these jurisdictions into greater transparency and cooperation with tax authorities worldwide. The Common Reporting Standard represents the most ambitious attempt to create automatic exchange of tax information between countries, requiring financial institutions to identify foreign tax residents among their clients and report their account information to both their home countries and countries of tax residence, though implementation has been uneven and enforcement remains challenging. Country-by-country reporting requirements for multinational corporations represent an attempt to create greater transparency around where profits are actually earned versus where they are reported for tax purposes, though these reports are typically shared only between tax authorities rather than being made public, limiting their effectiveness in creating public accountability for corporate tax behavior. Beneficial ownership registries have been promoted as a mechanism for identifying the ultimate human owners of complex corporate structures, though many British territories have resisted making these registries public or have created registries with significant exceptions and limitations that preserve much of the opacity that makes offshore structures attractive to their clients.

Anti-tax avoidance directives from organisations like the European Union have attempted to create common standards for addressing tax avoidance schemes, but their effectiveness is limited by the ability of offshore jurisdictions to remain outside these frameworks while continuing to offer services to clients within the jurisdictions covered by these directives, creating ongoing opportunities for regulatory arbitrage and continued tax base erosion.

British Government Ambivalence

The economic benefits derived by the United Kingdom from its network of offshore territories create a fundamental conflict of interest in any reform efforts, as the offshore finance industry contributes substantially to the City of London’s continued dominance as a global financial centre and generates significant economic activity that benefits the broader British economy. London-based banks, law firms, accounting firms, and other professional service providers earn billions of pounds annually from facilitating offshore structures and serving clients who utilise British overseas territories for tax optimisation, creating powerful domestic constituencies that resist meaningful reform efforts that might reduce this business. The political costs associated with ongoing tax avoidance scandals create domestic pressure for action, particularly when high-profile cases reveal that wealthy individuals and large corporations are paying lower effective tax rates than middle-class taxpayers, but this political pressure often dissipates quickly unless sustained by ongoing media attention and must compete with economic interests that have more consistent and focused political influence. Growing international pressure from partner countries and international organisations creates additional political complications, as the UK government must balance its relationships with allies who view British territories as undermining their tax systems against domestic economic interests that benefit from the current arrangements.

The limited leverage available to the UK government over its overseas territories creates practical obstacles to reform that go beyond political considerations, as the constitutional autonomy that makes these territories attractive for financial services also constrains the UK’s ability to impose reforms unilaterally. Any meaningful changes require either voluntary cooperation from territory governments or fundamental constitutional changes that could trigger legal challenges and political crises that might ultimately prove more costly than the status quo, creating a situation where even well-intentioned reform efforts face substantial practical and legal obstacles.

Offshore Territories Dodge Transparency Requirements

Offshore Territories governments consistently dodge transparency requirements by arguing that financial services provide essential economic diversification for small jurisdictions that have limited alternative sources of economic activity, particularly given their geographic isolation, small populations, and limited natural resources. These arguments carry significant weight because many of these territories genuinely lack obvious alternative economic development strategies that could provide comparable levels of prosperity and employment for their residents, creating legitimate concerns about the social and economic consequences of major changes to their business models. The competitive pressure argument maintains that increased regulation would simply drive business to non-British competitors without meaningfully improving global tax compliance or transparency, merely shifting the problem to other jurisdictions that may be less responsive to international pressure and less committed to maintaining even minimal regulatory standards. Territory officials argue that their jurisdictions already comply with international standards and that they have made significant improvements in transparency and cooperation in response to international pressure, though critics contend that these improvements often involve technical compliance that preserves the substance of bank secrecy and tax avoidance opportunities. Constitutional autonomy arguments invoke centuries-old arrangements and legal precedents to argue that fundamental changes to territory governance or regulation would violate historical agreements and constitutional principles that form the foundation of their relationship with the Crown, creating potential legal challenges that could prove costly and time-consuming to resolve, while uncertain to succeed in achieving meaningful reform objectives.

Global Tax Transparency and Minimum Global Tax Requirements

Global tax initiatives, particularly the OECD’s global minimum tax agreement, represent the most significant threat to traditional tax haven business models in decades, as they attempt to create floor rates below which multinational corporations cannot reduce their effective tax rates regardless of the sophistication of their offshore structures. These reforms could fundamentally undermine the value proposition of many British territories by eliminating the tax rate advantages that have attracted much of their international business, forcing these jurisdictions to find new ways to compete for international finance or face significant economic disruption.

Digital taxation initiatives present additional challenges to offshore tax planning strategies by attempting to tax multinational corporations based on where they generate sales and user activity rather than where they book profits, potentially reducing the effectiveness of profit-shifting strategies that have been central to the offshore finance industry. These initiatives recognise that traditional concepts of tax residence and profit attribution have become inadequate for addressing the realities of digital economy business models that can generate substantial economic value in high-tax jurisdictions while booking profits in low-tax territories with minimal economic substance.

Geopolitical tensions, particularly those arising from sanctions against Russia and other countries, have highlighted how offshore structures can undermine foreign policy objectives by providing mechanisms for sanctioned individuals and entities to evade restrictions and maintain access to international financial systems. This realisation has created new political pressure for reform that goes beyond traditional tax policy considerations to encompass national security and foreign policy objectives, potentially creating broader coalitions for reform that include defence and security constituencies alongside traditional tax reform advocates.

Public awareness of offshore tax avoidance has increased dramatically following high-profile data leaks that have provided unprecedented insight into the mechanics of global tax avoidance and the extent to which wealthy individuals and corporations utilise these structures. This increased awareness has created political pressure for reform that may prove more sustained than previous reform efforts, as public understanding of these issues has moved beyond abstract policy debates to concrete examples of how offshore structures enable wealthy individuals to pay lower tax rates than middle-class taxpayers while accessing superior public services and legal protections.

Conditional autonomy arrangements would represent a fundamental shift in the constitutional relationship between Britain and its overseas territories, making territorial autonomy contingent upon cooperation with UK policy objectives, including immigration policy, tax cooperation, and regulatory compliance. This approach would recognise that the benefits of British protection, legal systems, and international recognition come with corresponding obligations to support broader British policy objectives, potentially including requirements to provide facilities for asylum processing or other immigration-related activities when requested by the UK government. Revenue-sharing mechanisms could require territories to share tax revenue with the UK in exchange for defence, diplomatic, and legal services, recognising that these territories benefit substantially from British protection and international reputation while contributing minimally to the costs of providing these services. Such arrangements might involve territories paying annual fees based on their financial services revenue or sharing a percentage of their tax collections with the UK government, creating financial incentives for territories to cooperate with UK policy objectives while generating revenue that could help offset the costs of immigration processing and other shared policy challenges. Beneficial ownership transparency requirements could mandate public beneficial ownership registries across all British territories, eliminating much of the corporate secrecy that makes these jurisdictions attractive for tax avoidance and financial crime while maintaining their ability to offer other competitive advantages such as efficient incorporation procedures, sophisticated legal systems, and favourable regulatory environments. Public registries would enable tax authorities, law enforcement agencies, and civil society organisations to identify the ultimate human owners of complex corporate structures, dramatically reducing the utility of these structures for illicit purposes. Financial crime cooperation mechanisms could establish automatic information-sharing arrangements for law enforcement purposes, enabling UK and international law enforcement agencies to access information about suspicious financial activities in British territories without requiring lengthy legal processes or formal requests that can be delayed or denied by local authorities. This would recognise that financial crime often spans multiple jurisdictions and requires rapid information sharing to be effectively investigated and prosecuted.

A System Built on Contradictions, Institutional Corruption and Criminality

The inability to house asylum seekers on Jersey while that same island facilitates billions in tax avoidance represents more than just an administrative inconvenience—it reveals the fundamental contradictions at the heart of Britain’s post-imperial constitutional arrangement. The same legal frameworks that insulate British territories from UK taxation and regulation also prevent their use for politically difficult but legally necessary functions like immigration processing. This arrangement serves the interests of mobile capital while constraining democratic governance and policy implementation.

The spider’s web of British offshore territories represents one of the most sophisticated systems for tax avoidance ever created, facilitating massive wealth concentration while undermining tax bases globally. Yet this same system’s constitutional protections mean that when the UK government faces the humanitarian and political challenge of managing asylum seekers, it cannot simply commandeer these territories for public policy purposes. This paradox will likely persist until there is fundamental reform of either the constitutional relationship between Britain and its territories or the international tax system that makes offshore finance so profitable. Until then, the dinghies crossing the Channel will continue to highlight the absurdity of a system where tax avoiders enjoy easy access to British territories while asylum seekers are kept firmly away—not by British policy choice, but by the very legal structures that make tax avoidance possible. The ultimate irony is that a system designed to facilitate the free movement of capital has created constitutional obstacles to the sovereign management of human movement, even in times of political crisis. In this way, the needs of offshore finance have come to constrain the basic functions of democratic governance, revealing who the British constitutional system ultimately serves.

READ MORE:

https://www.fedortax.com/blog/global-loss-of-us-492-billion-for-underreported-offshore-tax

https://offshoreleaks.icij.org/nodes/80139510

https://offshoreleaks.icij.org/nodes/110007715

https://offshoreleaks.icij.org/nodes/80104896

https://offshoreleaks.icij.org/nodes/82005286

https://offshoreleaks.icij.org/nodes/82001401