The Buy Now Pay Later sector has emerged as one of the most consequential developments in consumer finance since the proliferation of subprime credit cards in the early 2000s. With global transaction volumes exceeding $560 billion projected for 2025 and growth rates approaching 14% annually, BNPL has transitioned from a fintech novelty to systemic significance. This review examines the credit exposure architecture of the sector, analyses the financial vulnerabilities of market leader Klarna following its September 2025 initial public offering, and assesses whether parallels to the 1920s instalment credit boom presage broader financial instability.

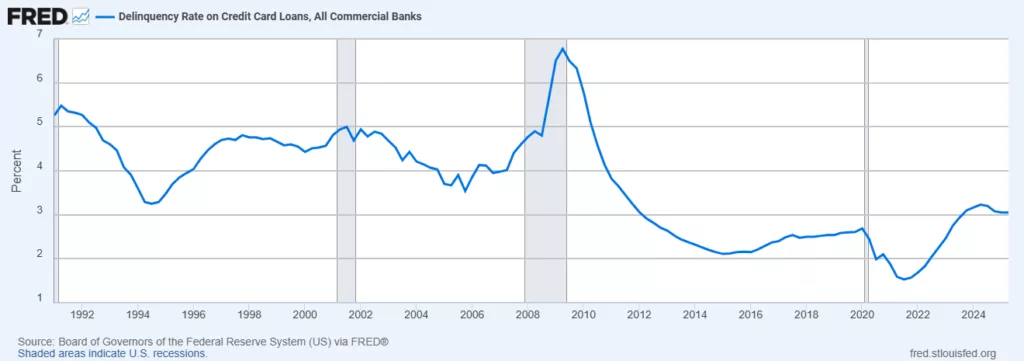

Our analysis reveals troubling divergences between reported delinquency metrics and actual financial performance. While Klarna advertises delinquency rates below 1% on its core BNPL products, the company reported $136 million in consumer credit losses during the first quarter of 2025 alone, contributing to a net loss of $99 million that more than doubled year-over-year losses. Industry-wide data presents an even more concerning picture, with approximately 30% of BNPL instalments past due as of January 2025 and 43% of users reporting at least one missed payment. These figures suggest a sector experiencing severe credit stress despite operating in relatively benign macroeconomic conditions, raising profound questions about resilience during genuine economic distress.

The historical comparison to the 1920s instalment credit expansion proves instructive but not deterministic. Both periods featured rapid democratisation of consumer credit, light regulatory oversight, and acceleration of consumption beyond sustainable income levels. However, critical differences in institutional architecture, regulatory frameworks, and relative scale suggest BNPL alone is unlikely to precipitate a systemic crisis comparable to the Great Depression. Nevertheless, the sector functions as a canary in the coal mine, revealing dangerous fragility in consumer balance sheets and merchant revenue models that could amplify and transmit shocks during the next economic downturn.

Market Architecture and Credit Exposure Analysis

The global BNPL market exhibits exponential growth characteristics that warrant careful scrutiny from both market participants and prudential regulators. Transaction volumes grew from approximately $14.5 billion during the 2022 holiday season to $18.2 billion in 2024, with single-day records reaching $991.2 million during Cyber Monday 2024. These figures represent not merely incremental growth in an established credit channel but rather the emergence of an entirely new consumer credit architecture operating largely outside traditional banking regulation.

Market valuation metrics underwent dramatic recalibration during 2024 and 2025 as investors confronted the reality of structural profitability challenges. Klarna, once valued at $45.6 billion during its 2021 funding round, completed its September 2025 initial public offering at a $14 billion valuation, representing a 69% decline despite intervening market growth. The company’s shares closed their first trading day at $45.82, yielding a market capitalisation exceeding $17 billion, but this premium reflects IPO scarcity rather than fundamental conviction about the business model’s sustainability. Bloomberg Intelligence analysts estimated fair value between $12 billion and $16 billion, suggesting even the reduced IPO valuation incorporated optimistic assumptions about margin improvement and credit performance.

The fundamental economics of BNPL reveal why profitability remains elusive despite rapid revenue growth. Providers like Klarna pay merchants immediately upon transaction authorisation, then assume full collection risk from consumers over the subsequent six to eight weeks. This model inverts traditional payment processing, where merchants bear chargeback risk while payment processors collect fixed fees with minimal credit exposure. During the first half of 2025, Klarna operated with an expense-to-revenue ratio of 109%, indicating the company spent more than one dollar for every dollar of revenue generated. Such metrics are unsustainable outside venture capital-subsidised growth phases, yet they characterise not aberrant performance but rather the structural reality of competing in BNPL markets.

Credit exposure concentrates in demographic cohorts least equipped to absorb economic shocks. Generation Z and millennial consumers account for the vast majority of BNPL usage, populations characterised by limited savings, high existing debt burdens from student loans, and employment concentrated in sectors vulnerable to recessionary layoffs. Consumer behaviour studies reveal that 43% of BNPL users have missed at least one payment, with younger cohorts disproportionately represented among delinquent accounts. This demographic concentration creates correlated default risk, where macroeconomic shocks affecting youth employment could trigger cascade failures across BNPL portfolios simultaneously.

The invisibility of BNPL debt in traditional credit reporting systems represents perhaps the most significant structural vulnerability in contemporary consumer credit markets. Most BNPL loans do not appear on credit bureau reports, meaning traditional lenders making mortgage, auto, or credit card underwriting decisions cannot assess applicants’ total payment obligations accurately. This information asymmetry enables what financial economists term “debt stacking,” where consumers accumulate multiple BNPL obligations across different providers without any single lender possessing visibility into total indebtedness. Anecdotal evidence suggests consumers frequently maintain concurrent BNPL loans from four or more providers, creating total payment obligations that exceed prudent debt-to-income ratios but remain invisible to credit scoring algorithms.

Klarna Case Study: Anatomy of Fintech Fragility

Klarna’s September 2025 initial public offering provides unprecedented transparency into BNPL economics, revealing business model characteristics that suggest broader sector vulnerabilities. The company reports 100 million active consumers globally and has established dominant market positions across European and North American markets. Yet despite this scale and network effects that should confer pricing power, Klarna continues posting substantial losses that expanded rather than contracted during 2025. The company’s reported credit metrics present a paradox that demands explanation. Klarna advertises delinquency rates of 0.88% on its core BNPL product for the second quarter of 2025, down from 1.03% the previous year, and 2.18% on its longer-term Fair Financing product. These figures compare favorably to credit card delinquency rates and suggest a well-underwritten portfolio. However, first-quarter 2025 financial statements revealed $136 million in consumer credit losses alone, contributing to a net loss of $99 million that exceeded $47 million in losses the previous year. Simple arithmetic reveals that credit losses of this magnitude require either dramatically larger loan portfolios than publicly disclosed, higher effective default rates once charge-offs and collection costs are included, or some combination of both. Several explanations reconcile this apparent discrepancy between reported delinquency rates and actual credit losses. First, the definition of delinquency in the BNPL context differs fundamentally from traditional lending. A BNPL loan might have a single late payment triggering intensive collection efforts and partial charge-offs without meeting the technical definitions of delinquency if the consumer makes sporadic subsequent payments. Second, the short duration of BNPL loans means that loans transition from current to charged-off status much faster than instalment loans or credit cards, potentially understating delinquency snapshots while losses accumulate. Third, Klarna’s global operations span jurisdictions with vastly different collection environments and consumer protection regimes, meaning aggregate statistics may obscure considerable geographic variation in actual credit performance. The valuation trajectory from $45.6 billion in 2021 to $14 billion at IPO reflects investor recognition of these structural challenges. Public market investors demanded a 69% valuation reduction before providing permanent capital, and even this reduced valuation assumes significant operational leverage improvements and margin expansion that may prove elusive in competitive markets. The company’s ability to more than double its monthly active users in August 2025 compared to the prior year demonstrates continued growth momentum, but growth without profitability increasingly appears unsustainable absent a fundamental business model transformation. Klarna’s regulatory positioning creates additional uncertainty. The company operates in a jurisdictional grey area where it provides consumer credit without maintaining bank capital ratios or submitting to bank supervision. This light-touch regulation conferred competitive advantages during the growth phase but creates existential risk if regulators impose bank-like requirements retroactively. The Consumer Financial Protection Bureau’s May 2024 interpretive rule attempted to classify BNPL providers as credit card issuers subject to Truth in Lending Act requirements, though the agency subsequently reversed this position in 2025 following a political transition and industry litigation. This regulatory volatility compounds investor uncertainty about whether current business models remain viable under future regulatory regimes.

The 1920s Parallel: Instalment Credit and Economic Instability

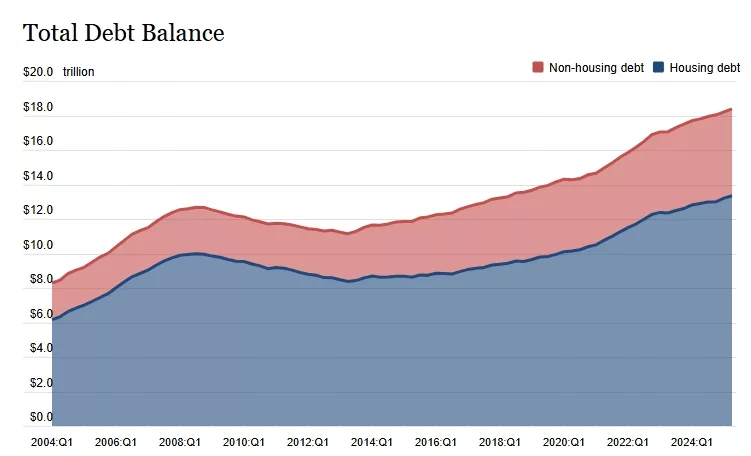

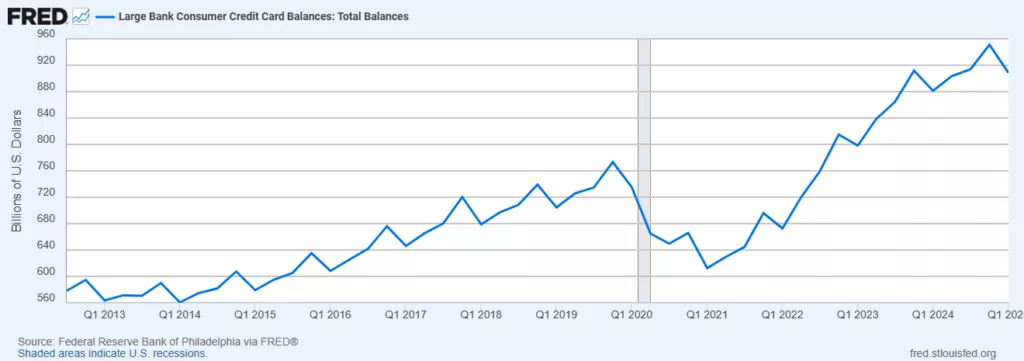

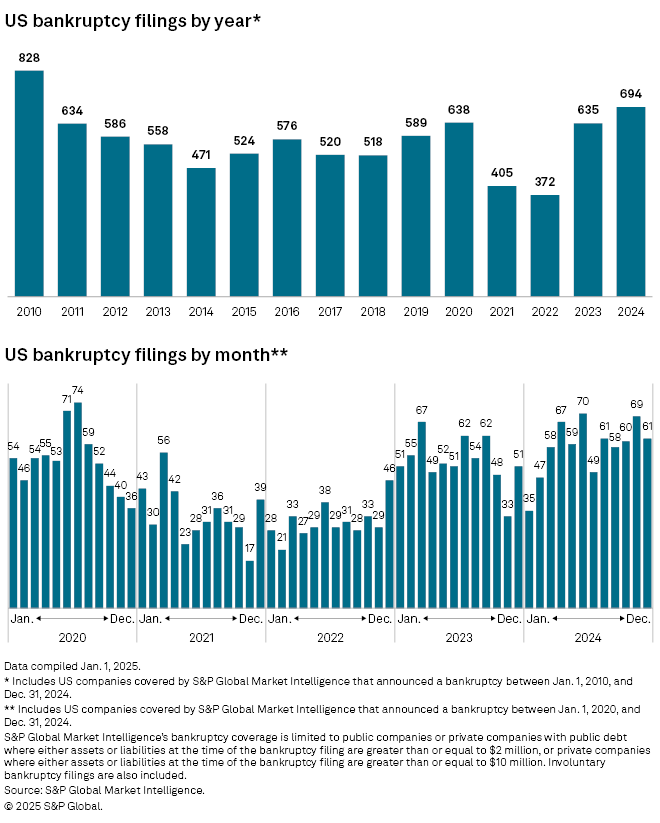

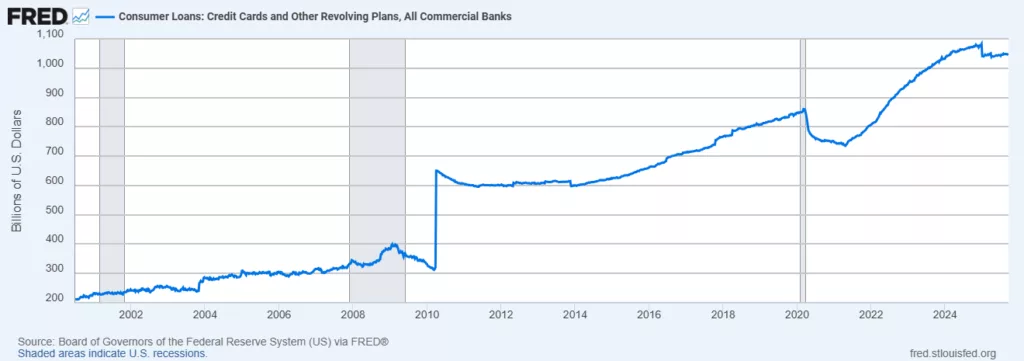

Historical analysis reveals striking parallels between contemporary BNPL growth and the instalment credit boom that characterised the American economy during the 1920s. Instalment credit gained widespread acceptance during that decade, particularly for financing automobiles, household appliances, and other consumer durables. Specialised finance companies issued cash orders payable in instalments that leading retailers accepted for virtually any goods except food, creating credit availability that transformed consumer behaviour and accelerated economic activity. The sociological impact of instalment credit in the 1920s resembles BNPL’s contemporary influence. Credit transitioned from a stigmatised necessity to a mainstream financial tool, enabling middle-class consumers to acquire goods previously accessible only to the wealthy. Commercial banks, initially hesitant to engage in consumer lending, established instalment loan departments and expanded mortgage lending in response to competitive pressure from finance companies. This democratisation of credit access drove economic growth but also facilitated consumer overextension as households accumulated multiple credit obligations without comprehensive financial planning or regulatory oversight. The 1929 market crash and subsequent Great Depression revealed the fragility of credit-dependent consumption. The sharp contraction in asset values and employment resulted in widespread payment defaults as consumers lost the income necessary to maintain instalment obligations. These defaults propagated through the financial system as specialised finance companies and their bank creditors absorbed losses, constraining credit availability precisely when economic conditions demanded counter-cyclical expansion. The procyclical nature of instalment credit, expanding during booms and contracting during busts, amplified rather than dampened economic volatility. Critical differences between the 1920s and contemporary contexts suggest that BNPL alone is unlikely to trigger comparable systemic instability. The relative scale proves determinative—BNPL represents a small fraction of total consumer credit, whereas instalment debt constituted a much larger share of household obligations during the 1920s. Total U.S. household debt currently exceeds $17.9 trillion, including $12.6 trillion in mortgages, $3.2 trillion in student and auto debt, and $1.2 trillion in credit card balances. BNPL exposure, while growing rapidly, remains orders of magnitude smaller than these established credit categories. Modern institutional architecture provides substantial buffering capacity, absent during the 1920s. Deposit insurance eliminates the bank run risk that converted liquidity problems into solvency crises during the Great Depression. The Federal Reserve’s evolution into an effective lender of last resort enables monetary authority intervention to prevent credit market seizures. Automatic fiscal stabilisers, including unemployment insurance and progressive taxation, provide income support during downturns that dampen default cascades. These institutional innovations, products of New Deal reforms and subsequent financial crisis responses, fundamentally alter the transmission mechanisms through which consumer credit stress propagates into systemic instability. Nevertheless, the historical parallel illuminates concerning dynamics. Both periods feature rapid credit expansion to demographically concentrated populations with limited experience managing debt. Both involve credit products marketed as consumer convenience rather than borrowing, obscuring the obligations being assumed. Both concentrate credit provision in specialised institutions operating outside traditional banking regulation. And both demonstrate how credit-enabled consumption can exceed sustainable income levels, creating illusions of prosperity that reverse violently during economic contractions.

Regulatory Vacuum and Systemic Risk Transmission

The regulatory treatment of BNPL exemplifies the challenge of maintaining financial stability amid rapid fintech innovation. BNPL providers extend credit but typically avoid classification as banks or credit card issuers, enabling operation with minimal capital requirements, light supervision, and limited consumer protection obligations. This regulatory arbitrage confers competitive advantages but creates systemic blind spots where regulators lack visibility into credit quality, consumer overextension, or emerging stress. The Consumer Financial Protection Bureau’s confused regulatory trajectory illustrates the difficulty of adapting credit regulation to novel products. In May 2024, the agency issued an interpretive rule classifying BNPL providers as credit card issuers under Regulation Z, subjecting them to Truth in Lending Act disclosure requirements, dispute resolution obligations, and other consumer protections. The industry immediately challenged this interpretation, arguing that BNPL loans structured as individual closed-end transactions with fixed payment schedules bear little resemblance to revolving credit card accounts. The impossibility of providing periodic statements for loans that mature in eight weeks or less highlighted the awkward fit between existing regulatory frameworks and BNPL product characteristics. Following the January 2025 political transition, the Bureau reversed course, announcing in May 2025 that it would not prioritise BNPL enforcement and subsequently withdrawing the interpretive rule entirely. Officials characterised the previous rule as procedurally defective and substantively misguided in applying open-end credit regulations to closed-end loan products. By June 2025, the agency confirmed it would not issue revised BNPL regulations, effectively returning the sector to its previous unregulated status. This regulatory volatility creates planning uncertainty for both providers and merchants while leaving consumer protections undefined. The regulatory vacuum creates several transmission channels through which BNPL stress could affect broader financial stability. First, funding dependencies connect BNPL providers to traditional banking institutions. Most BNPL companies finance their loan portfolios through warehouse credit lines from commercial banks, asset-backed securitisations purchased by institutional investors, or equity capital from venture funds and public markets. Klarna’s IPO prospectus revealed significant reliance on debt financing to fund loan originations, creating counterparty exposure for lending banks. If BNPL credit performance deteriorates sharply, losses would transmit to bank balance sheets through credit line draw-downs, securitisation impairments, and equity value destruction. Second, merchant dependencies create business disruption channels. Retailers increasingly structure merchandising and pricing strategies around BNPL availability, with studies showing that BNPL options increase average transaction sizes by 20-30%. If major BNPL providers suddenly tightened credit standards, failed operationally, or exited markets due to regulatory intervention, merchants would face immediate revenue shortfalls. Small and medium retailers with concentrated BNPL exposure could face liquidity crises, potentially triggering broader distress in commercial real estate and small business lending markets. Third, consumer behaviour feedback loops amplify downside risks. BNPL enables consumption above sustainable income levels during economic expansions, creating artificial demand that pulls forward future purchases. When economic conditions deteriorate or BNPL availability contracts, the reversal affects not merely incremental consumption but also baseline spending as over-leveraged consumers retrench. The concentration of BNPL usage among younger demographics means this demand destruction would disproportionately affect sectors serving millennial and Generation Z consumers, including fast fashion, electronics, and experiential retail. Fourth, information asymmetries prevent early detection of emerging stress. Because most BNPL debt remains invisible to credit bureaus and traditional underwriting processes, regulators and market participants cannot accurately assess household leverage or default risk. This opacity recalls the shadow banking opacity that contributed to the 2008 financial crisis severity, where off-balance-sheet vehicles and credit default swaps obscured true risk exposures until the crisis crystallisation. The lack of comprehensive BNPL reporting means systemic stress might remain undetected until it manifests in dramatic provider failures or merchant payment disruptions.

Delinquency Dynamics and Credit Performance Stress

Industry-wide delinquency data reveal credit performance substantially worse than individual provider disclosures suggest. Approximately 30% of BNPL instalments were past due as of January 2025, a figure representing tenfold or greater delinquency rates compared to traditional consumer credit products. Consumer surveys confirm this stress, with 43% of BNPL users reporting at least one missed payment. These statistics indicate widespread consumer difficulty managing BNPL obligations despite the relatively small individual loan amounts and short repayment periods. The demographic distribution of BNPL delinquencies provides insight into underlying vulnerabilities. Generation Z users demonstrate the highest delinquency rates, followed closely by millennials. These cohorts face structural economic challenges including high student debt burdens, stagnant wage growth relative to housing costs, and employment concentration in service sectors vulnerable to automation and economic cycles. The appeal of BNPL to these demographics reflects not consumer preference but rather economic necessity, as traditional credit card access remains limited for younger consumers with thin credit files or damaged credit histories. The paradox of high delinquency rates coexisting with continued rapid growth suggests adverse selection dynamics characteristic of credit market dysfunction. As BNPL providers compete for market share, underwriting standards deteriorate to capture incremental customers. The short-term revenue benefits of expanded originations manifest immediately in top-line growth metrics that attract venture funding and support high valuations. However, the long-term cost of credit losses emerges with considerable lag, particularly when young borrowers initially maintain payments using additional BNPL advances from competing providers. This pattern of robbing Peter to pay Paul creates artificial credit performance that collapses once consumers exhaust available BNPL sources. Comparison between Klarna’s reported delinquency rates and industry averages suggests either superior risk management or definitional differences that obscure comparable metrics. Klarna’s 0.88% delinquency rate on core BNPL products appears dramatically better than the 30% industry past-due rate, raising questions about measurement methodology. If Klarna’s superior performance proves real rather than definitional, it suggests the bulk of industry delinquencies concentrate among smaller providers with less sophisticated underwriting and collection capabilities. This concentration would increase systemic fragility, as numerous small provider failures could trigger merchant disruption and consumer confusion even while market leaders survive. The procyclical nature of BNPL credit quality represents perhaps the greatest systemic concern. Current delinquency rates emerged during relatively benign macroeconomic conditions, with unemployment near historic lows and consumer spending supported by pandemic-era savings and fiscal transfers. The deterioration in credit performance despite favourable conditions suggests profound vulnerability during genuine economic stress. A recession producing 8-10% unemployment and negative income shocks would likely drive BNPL delinquencies to levels incompatible with business model survival for most providers.

Macroeconomic Implications and Contagion Channels

The macroeconomic significance of BNPL extends beyond the sector’s absolute size to encompass its role in consumption dynamics and financial stability architecture. BNPL effectively lowers the immediate cost of consumption by fragmenting payments across multiple periods, enabling purchases that consumers would defer or forego if required to pay immediately. This credit-enabled consumption increases aggregate demand during economic expansions but creates dangerous fragility during contractions. The multiplier effects of BNPL availability deserve particular attention. When consumers use BNPL to purchase goods, merchants receive immediate payment from BNPL providers, supporting inventory investment and employment. This initial spending generates additional economic activity as merchants and their suppliers spend the proceeds. However, the subsequent BNPL payment obligations reduce consumer disposable income in future periods, constraining future consumption. The intertemporal substitution remains approximately neutral during stable economic conditions but becomes problematic during transitions between growth and contraction. Consider a stylised scenario where BNPL suddenly becomes unavailable due to provider failures, regulatory intervention, or dramatic credit tightening. Consumers who previously financed 20% of purchases through BNPL would need to either increase current income, reduce consumption, or shift to alternative credit sources. Increasing income proves difficult in short timeframes, particularly during recessionary conditions. Reducing consumption by 20% would trigger dramatic demand destruction affecting retailers, manufacturers, and service providers. Shifting to credit cards or personal loans faces capacity constraints, as consumers with BNPL dependence typically have limited access to traditional credit or have already exhausted available lines. Concentration of BNPL usage in specific retail categories amplifies sector-specific impacts. Apparel, footwear, electronics, and home furnishings demonstrate the highest BNPL penetration rates, with some online retailers reporting that 25-30% of transactions involve BNPL payment methods. These sectors would experience disproportionate demand shocks if BNPL contracted, potentially triggering retail bankruptcies, commercial real estate distress, and employment losses. The geographic concentration of retail employment in economically vulnerable regions would transform BNPL stress into localised economic crises.

International contagion represents an underappreciated dimension of BNPL systemic risk. Klarna operates across 45 countries with significant market positions in Sweden, Germany, the United Kingdom, and Australia, in addition to the United States. Other major providers, including Afterpay, Affirm, and PayPal, similarly maintain international operations. A credit crisis originating in one jurisdiction could propagate globally through both direct financial channels and behavioural spillovers as consumers in unaffected markets anticipate similar credit contraction. The interaction between BNPL stress and monetary policy transmission creates additional complexity. Central banks attempting to stimulate economies during recessions rely on credit channel transmission, where lower policy rates reduce borrowing costs and encourage consumption and investment. However, if BNPL providers respond to deteriorating credit performance by tightening underwriting standards or exiting markets entirely, this non-bank credit channel would contract precisely when monetary policy seeks expansion. The resulting credit crunch would offset monetary stimulus, reducing central bank policy effectiveness and requiring more aggressive interventions to achieve desired macroeconomic outcomes.

Merchant Ecosystem Dependencies and Cascade Risks

The integration of BNPL into merchant business models has progressed beyond an optional payment method to structural revenue dependency for many retailers. E-commerce platforms particularly demonstrate deep BNPL integration, with payment options featured prominently during checkout and merchandising strategies designed around instalment affordability messaging. This dependency creates bidirectional risk where BNPL provider stress affects merchants while merchant failures impact BNPL provider portfolios. Merchants derive multiple benefits from BNPL integration beyond simple payment processing. Average order values increase 20-30% when BNPL options are available, as consumers purchase more expensive items or add additional products, knowing they can spread payments across time.

Cart abandonment rates decrease as price sensitivity diminishes when consumers focus on per-payment amounts rather than total cost. Customer acquisition costs decline as BNPL providers market directly to consumers, driving traffic to merchant websites and physical stores. These benefits have convinced merchants to accept BNPL terms that typically involve higher transaction fees than credit card processing, with merchants paying 4-6% compared to 2-3% for card payments. The merchant economics reveal troubling implications for sudden BNPL contraction. Retailers who structure pricing, merchandising, and financial projections around BNPL-enhanced revenue would face immediate margin compression and volume shortfalls if BNPL became unavailable. Small and medium businesses with limited financial buffers could face liquidity crises within weeks of BNPL disruption. Larger retailers with diversified payment options would experience slower erosion but still face significant impacts if BNPL represents 20-25% of transaction volume. The concentration of merchant exposure among specific retail categories creates potential cascade dynamics. If fashion retailers experience BNPL disruption simultaneously, the sector-wide stress could trigger supplier payment defaults, inventory liquidations, and commercial lease defaults. These merchant-level stresses would transmit to commercial real estate markets, textile manufacturers, logistics providers, and other ecosystem participants. The high leverage characteristic of retail sector balance sheets amplifies these transmission effects, as relatively modest revenue shortfalls can trigger covenant violations and acceleration of debt obligations. International merchants face additional currency and regulatory risks from cross-border BNPL operations. A European retailer accepting BNPL from a U.S. provider assumes foreign exchange risk between customer payment obligations and merchant settlement. Regulatory fragmentation creates compliance complexity as different jurisdictions adopt varying BNPL treatment. Merchants operating globally must navigate this patchwork of regulation while maintaining consistent customer experiences, creating operational complexity that increases implementation costs and error risk. The feedback loop between merchant and BNPL provider stress could create self-reinforcing downward spirals. If merchants reduce BNPL usage due to concerns about provider stability or increased fees, reduced transaction volume impairs BNPL provider economics further. This volume loss forces additional fee increases or credit tightening, driving more merchants to reduce BNPL dependence. The cycle continues until reaching either a stable equilibrium at a dramatically reduced volume or a complete market collapse if providers exit entirely.

Consumer Behaviour Pathologies and Financial Literacy Deficits

The psychology of BNPL usage reveals concerning patterns suggesting consumer misunderstanding of debt obligations and intertemporal financial planning. Marketing emphasises convenience and affordability while minimising the credit nature of transactions. Phrases like “pay in four” or “split your payment” obscure that consumers are borrowing money and creating legal payment obligations. The absence of interest charges for on-time payment further disguises the credit relationship, creating an illusion of costless deferred payment. Behavioural economics research identifies several cognitive biases that BNPL marketing exploits. Present bias causes consumers to overvalue immediate consumption relative to future payment obligations, making instalment structures particularly appealing even when economically equivalent to paying in full. Mental accounting leads consumers to categorise small periodic payments as affordable even when aggregate obligations exceed sustainable levels. Complexity aversion means consumers focus on per-payment amounts rather than conducting a comprehensive affordability analysis incorporating all existing obligations.

The debt stacking phenomenon represents the logical endpoint of these behavioural pathologies. Consumers maintain concurrent BNPL obligations from multiple providers, with each individual loan appearing manageable in isolation, but collective obligations exceeding income capacity. The lack of comprehensive credit reporting means consumers themselves may not fully understand their total BNPL exposure until facing synchronised payment deadlines. This information deficit affects not only consumers but also subsequent lenders, who make credit decisions without visibility into existing BNPL obligations. Financial literacy deficits compound these challenges. Surveys reveal substantial consumer confusion about BNPL terms, with many users not understanding late fees, collection processes, or credit reporting consequences. The targeting of younger demographics who have not yet developed financial management skills exacerbates these comprehension gaps. Educational interventions show limited effectiveness when competing against sophisticated marketing and frictionless user experiences designed to minimise cognitive engagement with financial consequences. The intergenerational wealth implications deserve consideration. Millennials and Generation Z face structural economic challenges, including high student debt, expensive housing markets, and stagnant wage growth relative to prior generations. BNPL provides immediate consumption capacity but creates payment obligations that reduce future financial flexibility. The opportunity cost of servicing BNPL debt includes foregone savings for home down payments, retirement accounts, or emergency funds. This intertemporal resource transfer from future to present consumption may provide short-term gratification but compounds longer-term financial vulnerability for cohorts already facing diminished economic prospects relative to their parents.

Comparative International Perspectives and Regulatory Divergence

The global nature of BNPL operations creates regulatory arbitrage opportunities and coordination challenges as different jurisdictions adopt varying approaches to sector oversight. European Union regulators have moved more aggressively than U.S. counterparts to impose consumer protection and prudential requirements on BNPL providers. The United Kingdom’s Financial Conduct Authority announced plans in 2024 to regulate BNPL products similarly to other credit arrangements, requiring affordability assessments, regulated marketing standards, and consumer protection rights, including ombudsman access for dispute resolution. Australia’s experience provides an instructive case study in BNPL regulation evolution. Afterpay originated in Australia and achieved a dominant market position before expanding internationally. Australian regulators initially adopted a light-touch approach, enabling rapid growth but also allowing consumer overextension. Subsequent reviews identified concerning delinquency patterns and financial hardship among BNPL users, prompting regulatory tightening, including affordability assessment requirements and enhanced consumer protections. The regulatory evolution in Australia demonstrates the pattern whereby authorities permit innovation but impose restrictions retrospectively once adverse consequences emerge. Scandinavian markets where Klarna originated demonstrate different regulatory dynamics. Sweden’s financial regulatory framework subjects BNPL providers to consumer credit regulation, including licensing requirements, capital adequacy standards, and conduct supervision. This more comprehensive oversight may explain Klarna’s apparently superior credit performance relative to U.S.-based competitors operating under lighter regulation. However, the regulatory compliance costs associated with European operations contribute to Klarna’s profitability challenges, illustrating the trade-off between consumer protection and business model viability. Emerging markets present distinct BNPL dynamics with different systemic implications. In markets with limited credit bureau infrastructure and thin financial histories for large population segments, BNPL providers cannot rely on traditional underwriting approaches. Alternative data sources, including mobile phone usage patterns, social media activity, and transactional histories from digital wallets, enable risk assessment but raise privacy concerns and potential for discriminatory outcomes. The rapid growth of BNPL in India, Southeast Asia, and Africa creates financial inclusion benefits but also heightens risks in jurisdictions with limited consumer protection enforcement capacity and weak bankruptcy frameworks. The lack of international regulatory coordination creates competitive distortions and supervisory gaps. BNPL providers can establish operations in jurisdictions with favourable regulatory treatment and serve customers globally through cross-border digital channels. This regulatory shopping undermines attempts by individual jurisdictions to impose comprehensive oversight, as providers can threaten to relocate operations or serve markets from offshore. International standard-setting bodies, including the Financial Stability Board and Basel Committee, have not yet developed BNPL-specific guidance, leaving national regulators to craft independent approaches that may prove inconsistent and inadequate.

Stress Scenarios and Tail Risk Assessment

Quantitative stress scenario analysis illuminates the potential magnitude of BNPL-related financial instability under adverse macroeconomic conditions. Consider a baseline scenario where a moderate recession increases unemployment from 4% to 8% over two quarters while household income declines 5% in real terms. Historical relationships between unemployment and consumer credit delinquencies suggest BNPL delinquency rates could increase from the current 30% industry average to 50% or higher, as younger workers face disproportionate layoff risk and the marginal borrowers using BNPL possess minimal financial buffers. The credit loss implications prove substantial even at moderate market penetration levels. If BNPL transaction volume reaches $100 billion annually in the U.S. market with average loan amounts of $150, this implies approximately 667 million BNPL originations. A 50% delinquency rate would produce 333 million delinquent loans. Assuming 60% eventual charge-off rates on delinquent accounts and $150 average balances, total credit losses would approach $30 billion. This figure compares to approximately $130 billion in total annual credit card charge-offs across the entire U.S. banking system, suggesting BNPL stress could represent a meaningful percentage of aggregate consumer credit losses. The feedback loops and second-order effects amplify direct credit losses substantially. BNPL provider failures would disrupt merchant payment processing, reducing retail sales and employment. Consumer credit score damage from BNPL defaults would constrain future borrowing capacity, reducing automobile purchases and home buying activity. The wealth effects from equity value destruction in BNPL provider stocks would reduce consumption by affected investors and employees. These cascading impacts could transform a $30 billion direct credit loss into $100 billion or more in aggregate economic impact through multiplier effects. The tail risk scenarios present even more concerning prospects. A severe recession comparable to 2008-2009, with 10% unemployment and a synchronised global downturn, would likely prove fatal to most BNPL providers. Delinquency rates approaching 70-80% would exhaust equity capital and trigger covenant violations on debt financing. The absence of government backstops comparable to deposit insurance or emergency liquidity facilities available to banks means BNPL provider failures would proceed through disorderly liquidation rather than managed resolution. The merchant disruption and consumer confusion from the sudden provider disappearance could trigger localised panics and accelerate economic contraction. Geographic concentration of tail risks deserves emphasis. If BNPL stress originates in one major market, the combination of direct financial losses, regulatory response, and behavioural spillovers could propagate globally within weeks through the internationally integrated operations of major providers. A crisis in European BNPL markets affecting Klarna could immediately impact U.S. operations through funding constraints, risk management reactions, and investor sentiment. This interconnection means that seemingly local BNPL stress could quickly acquire systemic character through contagion channels.

Policy Implications and Regulatory Recommendations

The analysis of BNPL systemic risks suggests several policy interventions are warranted to enhance financial stability while preserving beneficial innovation. First, comprehensive reporting requirements should mandate that all BNPL loans appear on consumer credit reports maintained by major bureaus. This transparency would enable both consumers and lenders to assess total payment obligations accurately, reducing debt stacking and improving underwriting quality across all consumer credit categories. The technical challenges of reporting short-duration loans with weekly or biweekly payment schedules should not prevent implementation, as technology solutions exist to capture and transmit this information efficiently. Second, regulatory authorities should impose capital adequacy requirements on BNPL providers proportionate to their credit risk exposures. The current exemption from bank capital requirements creates an unjustified competitive advantage while leaving providers vulnerable to credit cycle downturns. Risk-based capital standards would require BNPL providers to maintain equity cushions capable of absorbing losses during stress scenarios, enhancing resilience and aligning incentives toward sustainable underwriting. The specific capital ratios should reflect the higher delinquency rates and correlated default risks characteristic of BNPL portfolios relative to traditional consumer credit. Third, affordability assessment requirements should mandate that BNPL providers conduct creditworthiness evaluations before loan origination, considering existing debt obligations and income capacity. The current soft credit check approach proves inadequate to prevent consumer overextension. Comprehensive affordability assessments, similar to those required for mortgage originations, would reduce approvals for borrowers lacking sustainable repayment capacity. Implementation challenges, including concerns about financial inclusion, should be addressed through graduated requirements that permit simplified assessments for small-value loans while requiring comprehensive review for larger obligations or repeat borrowers. Fourth, consumer protection standards should clarify BNPL provider obligations, including transparent disclosure of terms, fair debt collection practices, and error resolution procedures. The current regulatory vacuum leaves consumers without clear rights when disputes arise regarding merchandise quality, unauthorised transactions, or collection harassment. Extending existing consumer credit protection frameworks to BNPL products would eliminate regulatory arbitrage while preserving flexibility for product innovation. The challenge lies in adapting regulations designed for traditional credit cards to accommodate the structural differences of instalment loans with short durations. Fifth, merchant payment protection mechanisms should ensure that sudden BNPL provider failures do not leave merchants holding worthless payment guarantees. Insurance mechanisms, trust accounts, or clearinghouse arrangements could protect merchants from counterparty risk when accepting BNPL payments. The moral hazard concerns from such protection must be balanced against systemic stability benefits from preventing cascade failures through merchant ecosystem disruption.

Sixth, international regulatory coordination should develop harmonised standards for BNPL oversight to prevent regulatory arbitrage and ensure consistent consumer protection across jurisdictions. The Financial Stability Board and Basel Committee should incorporate BNPL risks into broader fintech and consumer credit supervision frameworks, providing guidance that national regulators can adapt to local contexts while maintaining core consistency. The cross-border nature of major providers demands international approaches rather than fragmented national regulations that create compliance complexity without achieving supervisory objectives.

Lessons from History and Imperatives for Action

The comprehensive analysis of Buy Now Pay Later credit markets reveals a sector operating at the intersection of beneficial financial innovation and dangerous consumer credit expansion. The parallels to the 1920s instalment credit boom prove instructive rather than deterministic, highlighting recurring patterns in credit cycle dynamics while acknowledging critical institutional differences that alter systemic risk transmission. The democratisation of credit access provides genuine consumer benefits by enabling purchases that would otherwise require extended saving periods. However, these benefits come with costs, including consumer overextension, financial literacy exploitation, and macroeconomic fragility that demand policy attention. The case of Klarna illustrates the fundamental tension between growth and profitability that characterises BNPL business models. Despite achieving global scale with 100 million active users and dominant market positions across multiple jurisdictions, the company continues posting substantial losses that expanded during 2025. The mounting credit losses, despite reportedly low delinquency rates, suggest either measurement inconsistencies or structural business model flaws where the costs of credit provision and customer acquisition exceed sustainable revenue generation. The dramatic valuation reduction from $45.6 billion to $14 billion reflects investor recognition of these profitability challenges and skepticism about whether BNPL achieves viable unit economics at scale. The industry-wide delinquency data presents the most troubling dimension of current BNPL dynamics. The approximately 30% of instalments past due and 43% of users reporting missed payments indicate widespread payment difficulties despite benign macroeconomic conditions. These stress signals during economic expansion suggest profound vulnerability during a genuine recession when unemployment rises and incomes contract. The demographic concentration of BNPL usage among younger cohorts with limited financial buffers and high existing debt burdens amplifies vulnerability to economic shocks. Systemic risk assessment concludes that while BNPL alone is unlikely to trigger a financial crisis comparable to the Great Depression or 2008 financial crisis, the sector represents a meaningful financial stability concern warranting regulatory attention. The absolute scale of BNPL exposure remains small relative to total household debt, providing important buffering capacity. However, the sector’s role in consumption dynamics, merchant revenue models, and youth financial health creates transmission channels through which BNPL stress could amplify and accelerate economic downturns. The shadow banking character of BNPL operations, conducting credit intermediation outside traditional banking regulation and supervision, creates opacity that prevents early detection of emerging vulnerabilities.

The historical parallel to 1920s instalment credit offers both warning and reassurance. The warning lies in recognising how credit-enabled consumption can exceed sustainable income levels, creating artificial prosperity that corrects violently during economic contractions. The reassurance comes from acknowledging the dramatic improvements in financial system architecture, regulatory frameworks, and macroeconomic policy tools developed over the intervening century. These institutional innovations do not eliminate crisis risks but substantially reduce the likelihood that consumer credit stress triggers cascading financial collapse. The path forward requires a balanced approach that preserves BNPL benefits while addressing systemic vulnerabilities. Comprehensive reporting, capital adequacy requirements, affordability assessments, consumer protections, and international regulatory coordination can enhance resilience without stifling innovation. The alternative of continued regulatory neglect risks allowing vulnerabilities to accumulate until triggering a disruptive crisis or heavy-handed regulatory intervention that destroys value unnecessarily. The fundamental question is whether BNPL represents sustainable financial innovation or an unsustainable credit bubble. The mounting evidence of widespread delinquencies, provider losses, and consumer financial stress suggests the sector has expanded beyond sustainable boundaries. The correction may come through gradual regulatory tightening, market discipline from investor and merchant skepticism, or disorderly collapse during the next recession. Prudent policy intervention now can guide toward the first outcome while avoiding the chaos of the third.

Buy Now Pay Later sector stands at a crossroads. The choices made by regulators, providers, merchants, and consumers over the coming months and years will determine whether BNPL matures into a stable component of modern financial infrastructure or joins the long history of credit innovations that ended in crisis. The lessons of the 1920s remind us that democratizing credit access without corresponding improvements in financial literacy, consumer protection, and prudential oversight creates dangerous fragility. The imperative for policy action is clear, even if the political will to intervene before a crisis materialises remains uncertain.